In 1952, the American Surrealist Dorothea Tanning painted the strikingly fantastical La Truite au bleu (‘Poached Trout’), in which a girl dressed in pallid pink sits unaccompanied at the dining table, watching a fish leap out from a plate as more fish swim in a pool of water under the table. The ordered interior of domestic life takes a bizarre turn on Tanning’s canvas, much like our homes right now, as the world precariously tilts off its axis.

In lockdown, we are spending more time than ever at home. As we sequester ourselves from the outside, wrestling with inexplicable fatigue and navigating an ill-defined wedge of time, we also share cooking responsibilities with our families and come together at the dining table. Shamed by screen-time notifications — don’t just bring your appetite to the table, bring your attention too — the call of “Dinner is ready!” is one we’ve begun to seek succour in.

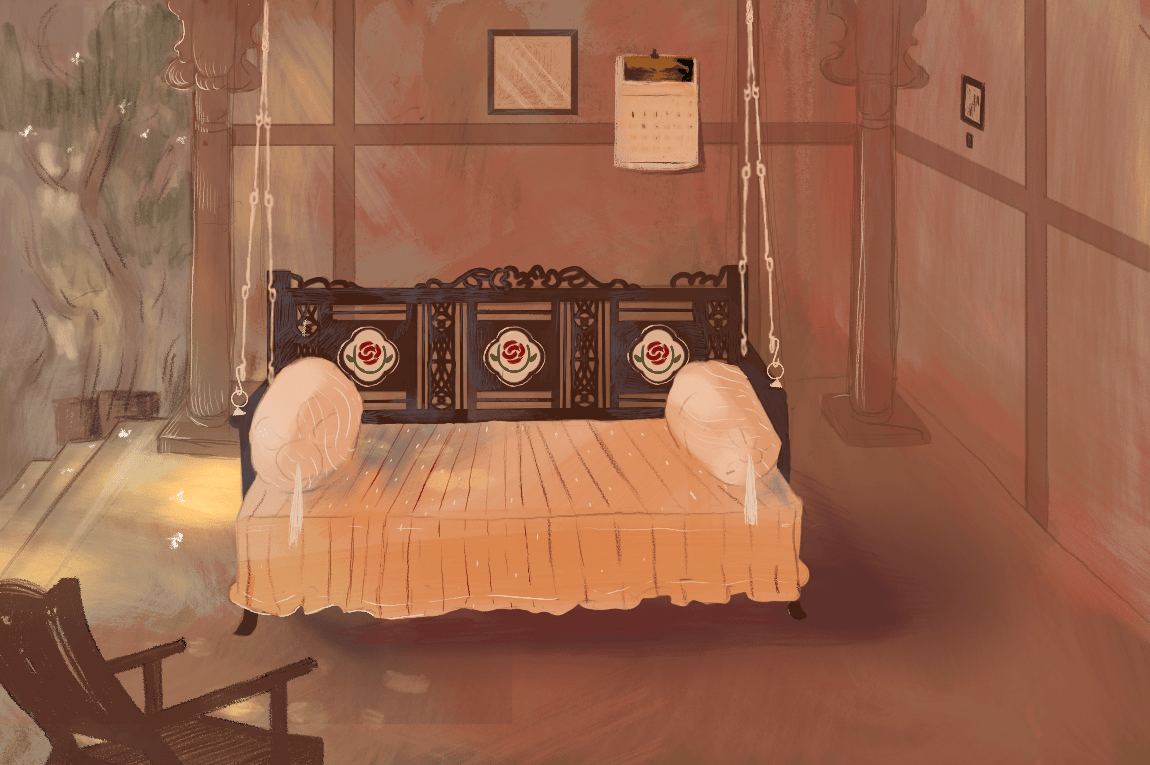

However, no one will profess to the dining table being their ‘preferred spot’ in the house. It barely comes close to the resuscitative pull of the bed, the well-worn embrace of a Bombay Fornicator, the appeal of the swing on ennui-filled evenings, or a diwan you can sink into with a book. For instance, my parents’ first dining table in a yet-unfurnished house back in 1990 was a modest white plastic one, before they graduated to the eight-foot-long teak one we use till date. In the frenzy of making decisions about the many accoutrements of a new house, the dining table was a relegated afterthought.

Customarily separated from the kitchen, the dining table is, in modern homes, more often than not, found in the same space as the kitchen or even integrated like an ‘island’ into the kitchen. The open-plan blueprint has constrained us to optimise every square inch of space. As mealtimes become fractured owing to erratic schedules and hunger pangs that don’t align, the ritual of the family eating together is a rare occurrence. We wolf down our food on the go, or plonked on the couch, or standing at the kitchen counter, compressing eating into our demanding lives. The versatility of the dining table was not quite acknowledged until the lockdown came along.

Since I do not possess a separate study table, the dining table has been my workspace for a considerable period while freelancing. In the last two months, it has become flexible enough to play multiple roles, its mise-en-scène changing as hours roll into days and days into Sisyphean hopelessness. While unsolicited newsletters dole out advice on how the ‘mood’ of your house can be elevated, all ephemeral adornments on the table — potted plants, crocheted doilies, and placemats that have seen better days — have made way for airing out just-purchased supplies. Scratches and stains and perimeters of coffee rings from years ago still linger, along with a freshly unfinished jigsaw puzzle. The table has also turned into a co-working space. The sibling suddenly wants to be in the same room as you, though it is only later you realise that the bookcase behind the table makes for a flattering backdrop for her Zoom meeting. The father has taken upon himself the task of chronologically arranging four decades’ worth of family photographs, a sprawl of memories worth dipping into. The sudden spurt of activity at the dining table has me thinking — should we have gotten a draw-table that can be conveniently extended? Or perhaps the kind that doubles as a ping-pong top?

The dining table is meant for affectionate repartee, for chats that digress, to confront love that has slowly soured, to discover the particulars and peculiarities of those you share a meal with, and even idle away by yourself, long after everyone has eaten and dispersed. It is a place that conjures memory — thanks are due to Proust’s ‘madeleine moment’. It is evocative of the reassuring endorsement from your parents for that first failed batch of chocolate cookies, a childhood loathing for chicken liver, and comfort in the simplest dal-khichdi when you’ve taken ill. It is meant for celebrations ― there is no moment too big or small to merit cake — and tracing cartographies of family recipes. The table is a crucible for a Sunday potluck lunch in the company of old friends and new — one that melds into dinnertime — where Pandi curry and dosas sit cheek by jowl with a caramelised onion-apple-cheese bake.

The dining table is where one has dozed off occasionally — burning the midnight oil while studying or in the run-up to a writing deadline. It is also where you daydream; in our current circumstances, to further extend an already protracted belatedness. As I write this, I am mentally recreating the mundane delight of the sights and sounds missed out on my daily walk back home: local trains crawling into Churchgate station every two minutes, a jamun-stained patch of the footpath upon exiting the subway, the local newsstand winding up for the day. The table is where light is followed during teatime — a glint of the sun on the rim of the cup, sluggishly making its way to the edge of the chair before waning.

Eating at the table is not without an unpalatable underside — no family paints a portrait of garrulous co-habitation. Fault lines in relationships are most evident at dinnertime rows, when even food cannot redeem indelibly seared silences. On days when you feel battered, the table is where reheated leftovers, or tears of loneliness with a tub of chocolate ice cream, are consumed. It is where, of late, a new-fangled, tendentious drama unfolds — how each grocery run must call for extreme forethought, morally conflicting arguments over whether to occasionally order in from your favourite restaurant, and the tedium of negotiating whose turn it is to do the dishes.

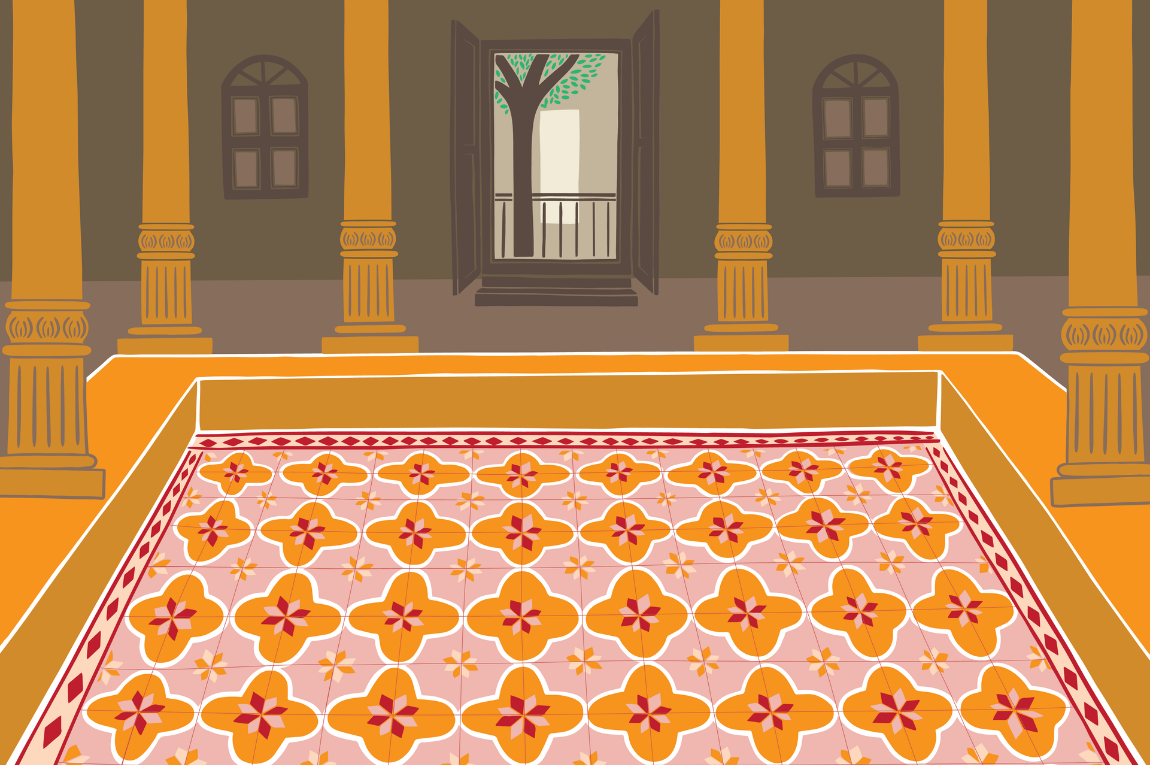

How far back does the dining table go? While for much of the thousands of years of human evolution we did not sit at tables, the rudimentary contraption of a slab of stone, wood or glass, supported by trestles, legs or a pillar dates back to circa 7th century BCE. The traditional dastarkhan — a Persian word that translates into a tablecloth spread on the floor for a lavish meal — was brought to the Indian subcontinent by the Turks during the late 13th century. The act of eating also harks back to a specific place that may not comprise a table: the cold marble floor at a friend’s home for a bountiful thaal, or the boot of a car at Delhi’s unfussy Alkauser for their sweetish, flaky warqi parathas, or leaning back on the grass while on holiday in faraway Krakow — cheap wine and smoky, spindle-shaped oscypek cheese in tow.

Outside the purview of the home, the table is also currently illustrative of the eateries we hope to return to. At the neighbourhood café, the corner table has often been host to the pleasure of my solo breakfast of akuri on buttered toast with a side of coffee and the day’s newspaper. It is a seemingly solitary activity, yet steeped in community — the surrounding chatter, overhearing amusing conversations, a familiar greeting from another ‘regular’. Community dining tables, on the other hand, can foster or frustrate, depending on your disposition. At most restaurants right now, these tables are perhaps joined together, repurposed as makeshift barricades, or used to line up attentively packaged delivery orders waiting to be picked up with utmost caution.

It isn’t for nothing that the dining table is synonymous with gratification — a reminder that food is one of the humblest ways we comfort ourselves, and each other. We must certainly look ahead to meeting a friend for that long-pending drink, or calling them home for another potluck, unlike what Tanning depicts in her strangely ominous landscape. But for now, we must feel truly fortunate and grateful to gather, at the table, loved ones who live with us and video call those who don’t.

Khorshed Deboo is an independent writer and text editor based in Bombay. She writes on art and culture and enjoys making photographs. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Mint Lounge, Scroll and The Hindu. She is Contributing Copy Editor at Domus India magazine and has worked as Curatorial Assistant (Visual Arts) with the Serendipity Arts Festival, Goa.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.