You could be a pirate. If you’ve downloaded a font off the internet, there’s a good chance it may have been a pirated version. Fonts, like everything else in the world, come at a price, and the sites — like fontsquirrel.com and dafonts.com — that don’t charge you usually list fonts procured from questionable sources. Even though these pirated fonts may be “free”, they’re not really very good. At best, you’ll be able to type wonkily spaced letters or an incomplete character set. At worst, you’ll have infected your system with a virus.

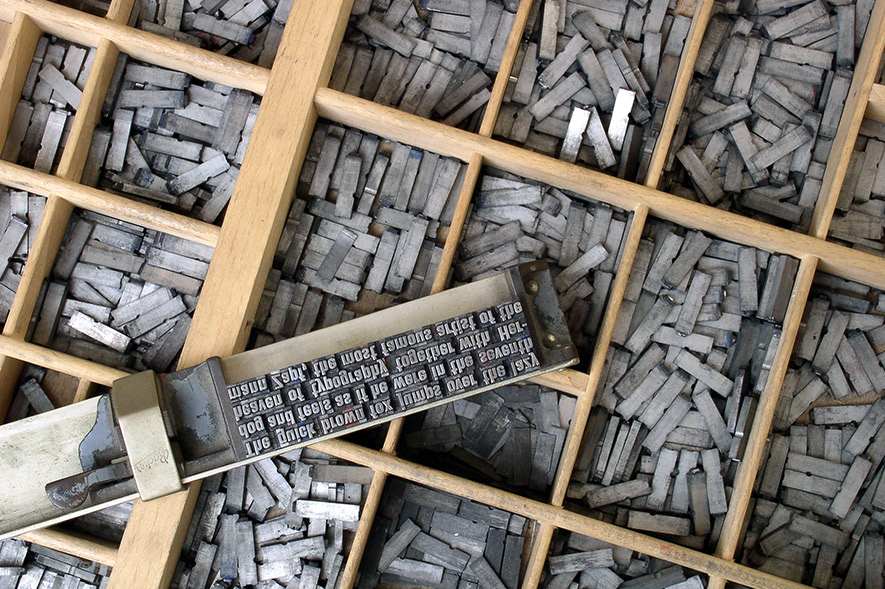

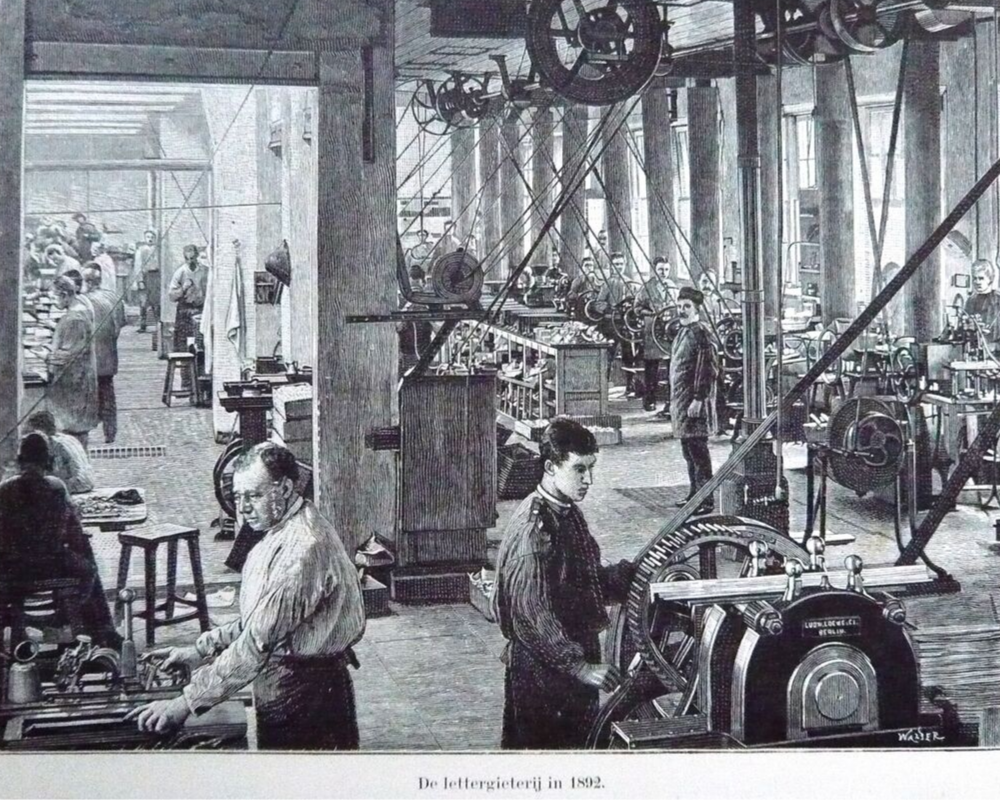

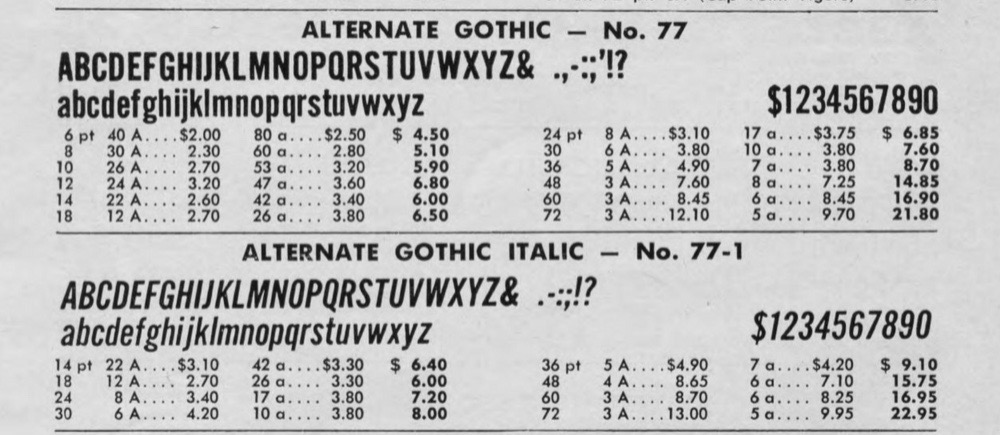

Once upon a time, fonts were things you could hold in your hands. They were cast in metal and sold by weight as physical objects. A look at the history of printing shows that the technology of fonts has changed many times — with it, pricing models have also evolved. Today, a font is essentially a collection of data. This is data that describes the outline of letterforms made using specialised software (like GlyphsApp or Robofont). These modern-day fonts that act like software can no longer be held in one’s hand. Instead, they are licensed based on where they are used.

Even though metal isn’t involved anymore, companies that make and sell fonts are still known as foundries. Today, a foundry can be an individual-run establishment or one that spans multiple teams across different continents, and the digitisation of fonts is what has allowed for this kind of collaborative, cross-continental work. These days, fonts are stored and distributed in files that can be easily duplicated; a simple copy-paste command will suffice. Users need to purchase a license from the foundry to access this font file and use it on desktops, websites or apps. Prices for fonts vary depending on the styles available, the size of the character set, the purpose of use, and the number of people accessing it.

What license do you need?

When it comes to font licensing, legal jargon can make it all seem daunting very quickly, but knowing the essentials can help. The most basic license provided by foundries is for desktops. This is a license that usually allows the font to be used on a handful of systems. For larger brands and companies, with thousands of employees and computers on which they need the fonts, a separate server license is more convenient to manage bulk licensing. Sometimes, it is easier and more financially viable for these companies to commission a brand new font because they would be able to own the license, either perennially or for a limited period of time. For instance, Apple currently uses the font San Francisco across all its devices, which means it’s customised for various uses, like the interface of the Apple Watch and the letters on laptop keyboards. Netflix also invested in Netflix Sans, its own custom font design, last year. These customisations can get extremely specific as well — Kolkata-based newspaper Anandabazar Patrika commissioned a bold weight of its Bengali font design to complement the existing design in use.

With design for the web, we’ve come a long way since the early days when only a few basic fonts were used. Today, every visitor to a website cannot be expected to have licenses of the fonts used in order to view them — hence the creation of ‘web fonts’. These are fonts that can be licensed by the owner of the website, based on its number of estimated visitors. An increase in visitors over the lifespan of the website would need the cost of the license to be adjusted accordingly.

All of these various licenses are usually listed in the End User License Agreement (EULA), a document that comes with every font you legally purchase. It’s an agreement that defines the terms for use, reproduction and distribution. While the EULA shouldn’t scare you away, if in doubt, the easiest way to get clarity is to write to the people behind it. Type designers, after all, have created fonts with the hope of it being put to use. That said, don’t expect freebies — you will be charged to license a font.

Why buy?

For communication designers, fonts are the foundation and make for a good investment. Many come at affordable rates — such as Maku, a font from Mota Italic, that supports Latin and Devanagari scripts and is a little over ₹1000. Purchasing single weights of fonts is also an option, without committing to the whole family. A lot of foundries provide free or reduced rates for students as well. If you’re not sold on spending, Google Fonts is a good go-to — the Internet giant offers a collection of Unicode-compliant fonts across of a range of scripts for free. Its efforts are less altruistic and more towards making content on the internet searchable, but you’re likely to find some quality fonts.

Newer models are also coming up that allow you to rent or subscribe to a list of the fonts by different foundries and designers. The Font of the Month Club by typeface designer David Jonathan Ross is now in its third year and delivers a font that is yours forever to your inbox every month, much like subscribing to a magazine. Future Fonts is another non-traditional model that allows designers to sell their work-in-progress designs . With every iteration, the price goes up, which in turn, incentivises users to buy in early, thus supporting designs that might have stayed in sketchbooks due to a lack of funding (users can avail of updated versions at no further cost).

There are innumerable fonts available to choose from today. By using legally obtained fonts, you’re supporting and ensuring the creation of good quality type, which then creates an enriched ecosystem with varied voices in textual communication. As always, all good things come at a price.

Tanya George is a type designer and typographer based in Mumbai. She is on Instagram and Twitter as @tanyatypes.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.