This story is a part of Issue #4 of Big Little Things, a limited-edition magazine, produced and published by Paper Planes for UnLtd India, a launchpad for early stage social entrepreneurs. Read more about this collaboration and UnLtd India here.

We associate sounds with our seasons — birdsong with summer, the crunch of snow in the mountains with winter, and the calls of amphibians with the monsoon. At this time, frogs across the continent come prepared to speak and be heard, so forests, waterbodies and our backyards turn into makeshift music festivals and dating venues. As the rain drums down on our roofs and against our windows, we hear the mating croaks of frogs. But despite this, if you ask someone who doesn’t think about amphibians for a living, it is likely that they’d describe them like this:

Icky.

Slimy.

Invisible.

As children, we saw them on the way to school, delighting in their jumping forms, were startled by an unexpected specimen outside our homes, and played boisterous games of leapfrog. We’re familiar with frogs, but we haven’t engaged with them. We don’t know why either. Most of us have never been crossed by a frog, or been gravely inconvenienced by one, but there it is. We simply do not think of them as wildlife.

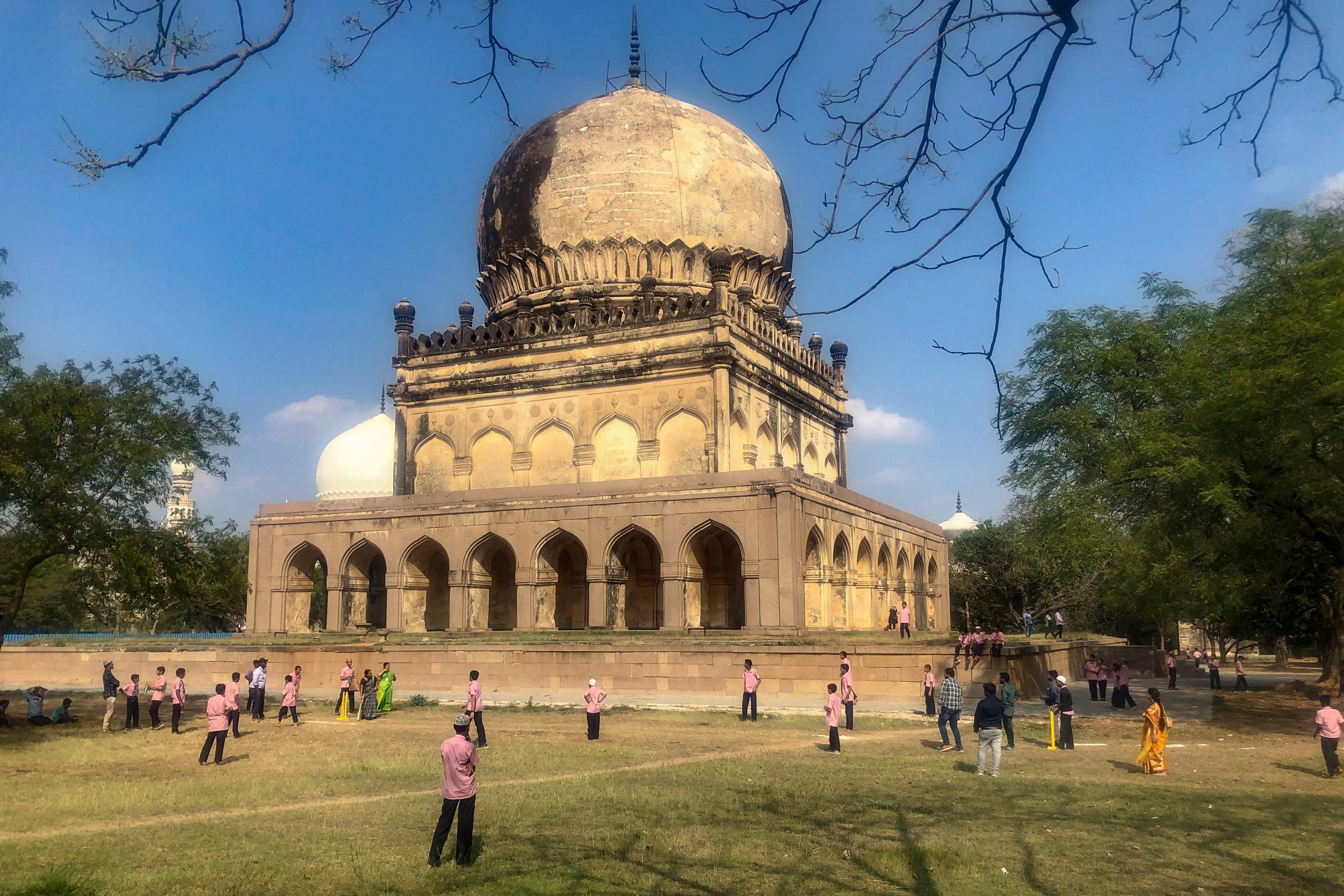

A small piece of land in Karnataka is attempting to urge us to look closer at the source of the monsoon song. Ashokavana is a 15-acre property, owned by Ashoka Vardhana GN and Dr Krishna Mohan. Situated near the Bisle Reserve Forest, in the Hassan district of Karnataka and about 250km from Bengaluru, it’s a forested wild space, hosting both wild creatures and wildlife enthusiasts. Kappe Goodu, literally translated as Frog’s Nest, is a small staying facility built on the property for those visiting the site. But in 2006, long before it was a space of exploration, it was a piece of agricultural land (under the patta system) that was up for sale, threatening the degradation of a beautiful landscape.

Back then, “the road from Kulkunda to the Bisle [Reserve Forest] gate bifurcated the Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary and Bisle Reserve Forest,” says Ashoka Vardhana, who owned a beloved bookstore in Mangalore at the time. It was a stretch that was uninhabited, except for “this private, abandoned cardamom estate.” Both men were part of a mountaineering group, the Aarohana Mountaineers and had been exploring the region for 30-odd years. “From our network, we heard that this land was under negotiation for tourism activities. This would fragment the forests and cause disturbance to the landscape, so Dr Krishi and I purchased it with our hard-earned money.”

Since 2006, the two men and their families ensured that this place became a space of study, knowledge-sharing and documentation of biodiversity. They didn’t plant a single tree or takeaway any, allowing the forest to grow as it would. They started to document the biodiversity that existed here and welcomed enthusiasts and volunteers to do the same. And so Ashokavana, bought as conservation action, became a base for citizen science.

Six years later, in 2012, Dr Gururaja KV, was asked to lead a frog walk in the neighbouring Bisle Reserve Forest. Dr Gururaja is a batrachologist — someone who studies amphibians — and has been studying frogs for two decades. His Pictorial Guide to Frogs and Toads of Western Ghats covers 73 of the 156 species of frogs and toads found in the Western Ghats. He has also studied their calls, working with bio-acoustic equipment to better understand amphibians, and is part of the faculty at the Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bengaluru. That frog walk at Bisle set the stage for several more years of research and discovery at Ashokavana.

For Dr Gururaja, that walk he led dispelled all the ‘science baggage’ he was carrying. “The enthusiasm of the motley group of enthusiasts, students, researchers was surprising,” he remembers. “They were there not for research, but merely because they were interested in frogs.”

Around this time, he had already begun to find the ‘ivory-tower’ attitude of science unpalatable. He preferred to participate, not to lead. “In the early years of my Ph.D, I had counterproductive notions about how science should be done. I worked in isolation, possessive already of the answers I was yet looking for,” he says. Over time, his regular presence at field sites and hotels started to prompt conversations — even suspicion — from locals and he began to answer questions about his work. “I started to wonder why I was treating all this data as my property, and started to talk with people who were interested, and soon even those that weren’t,” he laughs. The conversations led to networks, and that led to unprecedented data-sharing. “The more non-science people I spoke to, the more I started breaking difficult concepts down, to show people what their backyards hosted, and what that meant. That’s how we grow. This cannot be done alone.” Every year since then (until the COVID-19 pandemic), Dr Gururaja has led this special meeting of minds at Ashokavana, to communicate science in a way that is open and interactive.

At Ashokavana, since 2012, teams of researchers and wildlife enthusiasts have documented 38 species of frogs. The frog walks and research slowly graduated to the owners adding a stay facility just for the invited frog enthusiasts. Previously, Ashoka Vardhana says, “the participants used to stay in the local village houses but that was just for a few days. We wanted the research to continue round the year, so I readied a small container house [that’s 20 by 9ft, with four bunker beds, a kitchen and a bathroom]. It is powered by solar light and water from the stream. As a tribute to frogs, I named it Kappe Goodu. “Today, the place encourages genuine interest and questioning, doing away with a top-down approach. Be it a five-year-old or a 70-year-old, be it many different species found or just one, be it a convert or just an observer, it doesn’t matter.”

Still, what’s the big deal about frogs? Why should we care so much about amphibians? Because the smallest creatures around us tell us a lot about our habitats. And the frogs we see around us are actually a lot more connected to us than we think.

Dr Gururaja talks about the common toad for example. “These toads in your neighbourhood eat white termites. They’re capable of eating 160-odd insects in two minutes. Now imagine if we didn’t have toads around us. The termites would have no predators, and would be all over our books, our furniture, our lives. Think of the bullfrogs in India — which measure around 20–25cm, weighing about 400gm — and their diet of small rodents, birds, frogs. These creatures maintain order — for you.

Of course, while everything plays a role in nature, that’s not the only reason to pay attention to them, is it? Frogs are remarkable creatures. Oddly enough, even Dr Gururaja, started out by calling them “icky” just like the rest of us. “They all appeared the same to me in 1998,” he laughs. “It took me a month and half to be comfortable holding one. That changed after I looked at its eye. They are knowing, piercing eyes — they see through you. And it struck me. This creature has been around for 360 million years, and humans have been here for just two lakh years. “What the hell are we doing in the same place?”

“When we started discussing conservation in 1970s,” says Dr Gururaja, “there was a push for big animals — the tiger, panda, rhino, lion — and that’s fine, it was to shine the spotlight on conservation. But now, we have to talk about smaller species and their roles. If there is a forest fire, the tiger can run for long distances away from it, but what about the frog? Tiger numbers are cause for concern so I appreciate what we are trying to do. But there is a democratic way of doing this to bring in conservation action to all creatures — from the big to the smallest creatures. The tiger is a good entry point, but it’s not the endgame.” He points to a part in scientist Robin Moore’s book In Search of Lost Frogs , where Moore quotes David Attenborough, “The world wouldn’t change dramatically if the panda were to disappear, warning that focusing only on saving only the appealing creatures was a ‘mistake’.” Why? Because a frog in a stream tells you about the health and quality of that water — if the stream is not there, the frog is not there, and neither are the other larger mammals.

If we walked at Ashokavana, we’d see the agile Malabar gliding frog (Rhacophorus malabaricus) that glides from tree to tree in the dark of the night, like a tiny rocket. Or the Coorg yellow bush frog (Raorchestes luteolus), out in the night dressed like sunshine, its eyes lined with a beautiful blue. You might be forgiven if you assumed it enjoys standing out, considering its rather unique call — treee tink tink tink tink tink. Consider the Kempholey night frog (Nyctibatrachus kempholeyensis), which teaches us about perennial streams. Or the absolute delight of the elegant dancing frogs (Micrixalus elegans) of the Western Ghats. These frogs get their name from their courtship ritual, which resembles a dance — the frogs raise their legs at an angle to defend territory from an intruding male, just like tigers.

In 2008, two years after the frog walk at Bisle, Dr Gururaja launched Frog Watch, a citizen-science project under the India Biodiversity Portal. It allows anyone interested to contribute to the platform as well as to access information on frogs in India, in the process creating a vast database on these tiny creatures. The same attitudes at play on the frog walks at Ashokavana work here as well — inclusive moderators and citizen-scientist contributors.

But the digital divide of an online platform isn’t lost on Dr Gururaja. “The problem with apps is that it kind of makes the usage largely urban,” he says. “For deeper involvement from rural areas, we have to go to them. This is where we all need to mingle. There are places like Dandeli [Wildlife Sanctuary], which show significant local involvement. I need to do more to get inputs on board.”

In the meantime, hundreds have come to Ashokavana and left with a frog’s-eye view of the world. And at that size and scale, it’s a harsh world, no? It’s this kind of epiphany that flips the switch. A sudden understanding of an ancient species that has seen so much more, understands the planet in a way we cannot comprehend, earns its keep the way we haven’t even begun to try. It survives by water, and the seasons provide it direction.

When we refute climate change and pay no heed to changing monsoon patterns, to late arrivals and sporadic departures, we do a disservice to the creatures that depend on it for their very survival. We hear them in the monsoon, but we’re not particularly listening, because we’re not thinking about where they go when we don’t hear them (spoiler alert: nowhere, they’re just quiet). And even in the monsoon, they now have to speak louder. One study has shown that some species of frogs have started to call to mates at louder pitches in order to be heard over traffic and the cacophony of human lives. In the frog world, where the females prefer lower-pitched, soft-spoken men (but can’t hear them because of ambient noise), this might lead to the dwindling of populations years later. Not to mention, the call of the frog expends a lot of energy. It’s like us running a 400m sprint.

When we look closer at the individual lives of each animal and each species, conservation becomes so much more nuanced and layered. When we ask questions, we start to wonder about their homes, wetlands, waterbodies, cities. They ask almost nothing of us, but their presence might unlock the answers to so many questions we have about the health of our own habitats. In that, spaces like Kappe Goodu might be named after the frog, but the vision transcends to include its neighbours, big and small, and both animal and human. It asks us to merely look closer.

Track Wildlife as a Citizen Scientist

A handful of projects and websites worth bookmarking

India Biodiversity Portal

Home to Frog Watch, India Biodiversity Portal is an excellent contribution platform and encourages data collection across species. There are groups devoted to creatures like beetles and bats, moths and lizards.

eBird India

Bird Count India aims to inform and educate citizens by encouraging contributions, observations and building a community of dedicated enthusiasts and scientists. eBird India, managed by Bird Count India, is a portal designed for birders across the country.

Croc Watch

Croc Watch is a citizen-science initiative by the Voluntary Nature Conservancy to create a credible and wide-ranging database of the three crocodilian species in India.

Marine Life of Mumbai on iNaturalist.org

Marine Life of Mumbai, a citizen-led initiative and a project under the Coastal Conservation Foundation, documents and conducts outreach programmes on Mumbai’s shores. On iNaturaist.org, the organisation encourages citizens to share photos to a global network and database.

Read more about Big Little Things here.

Sejal Mehta is an independent writer and editor, based out of Mumbai.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.