Curating the collection at an 18th-century palace-museum, as I do in Jaipur, is an immersion into history, art, the objects, and of course, the architecture of the building. Work demands wandering around the palace, and for a breather from the overwhelming splendours of the past and the crowds that descend during peak season, I escape to Baradari.

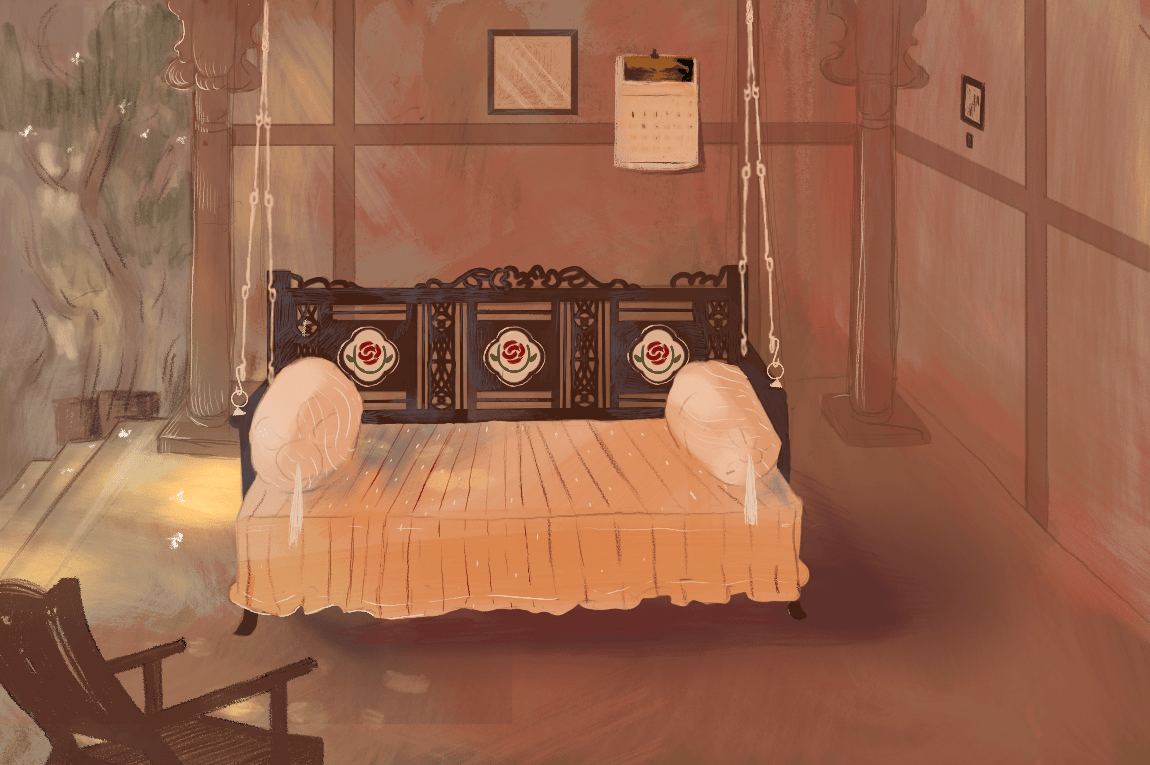

A baradari is a pavilion with twelve entrances in a set of three doorways ― a popular architectural trope in Rajput architecture ― ideal enough to catch a breeze and enjoy vistas. Baradari at Jaipur’s City Palace stretches the definition a bit and ought to be read as Bar-adari ― please forgive the awful pun. It is a quiet pitstop these days, where wine flows copiously like the fountain in the courtyard, and the marble imitates the wavy pattern of the hand-dyed leheriya textile innate to Rajasthan.

One has often wondered, and argued, over its ‘original use’. Was it a store or perhaps a place of rest for visitors? A PhD scholar has discovered a 19th-century traveller’s record that suggests the baradari was actually a bazaar comprising souvenirs and accoutrements you needed at the court. Over the years, the function of Baradari may have changed, and with it, the way it was done up too. Perhaps there were awnings mounted, carpets spread out, plenty of colourful fabric, and murals on the walls.

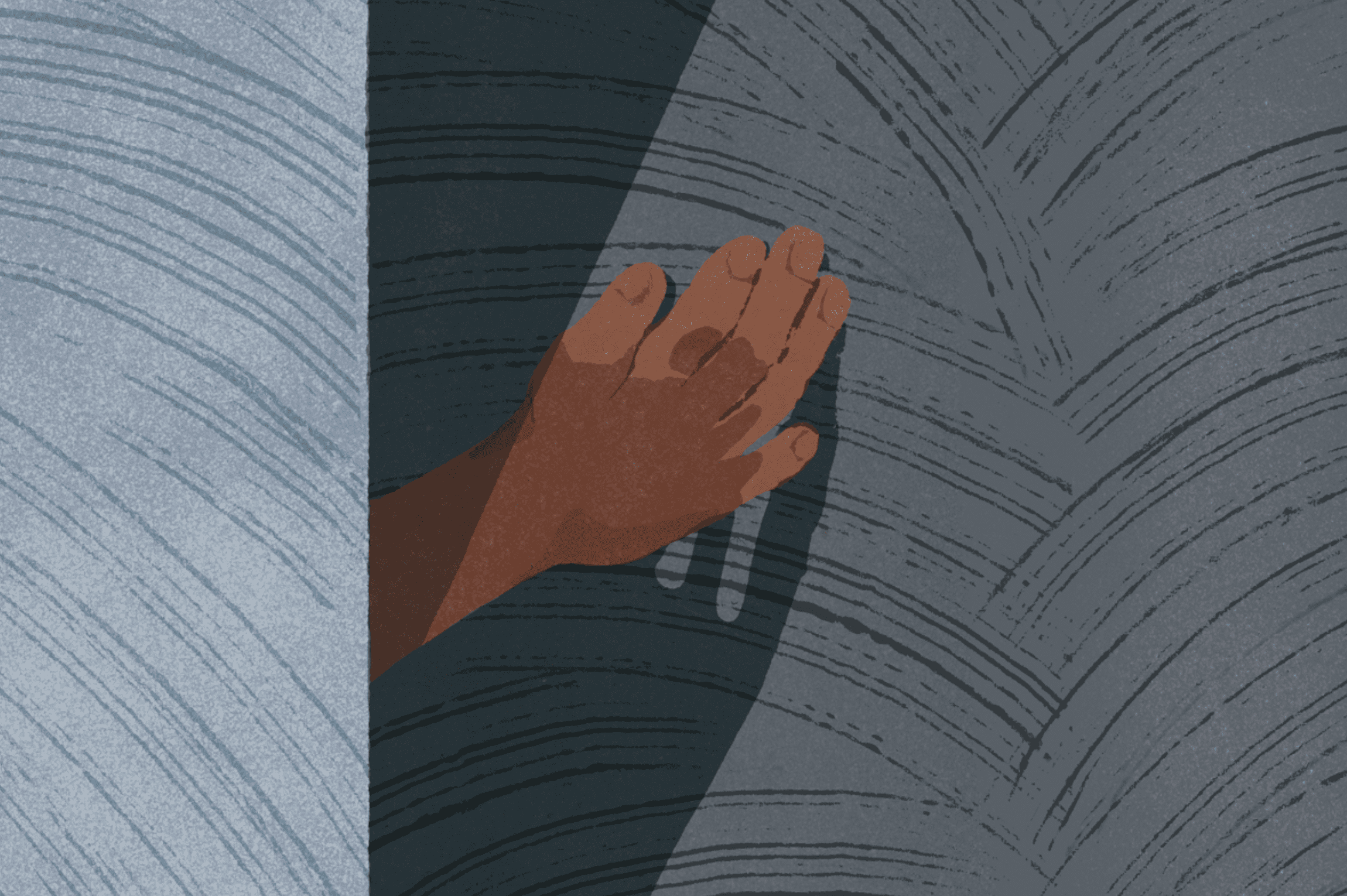

Lying inaccessible to visitors for a long time, the Palace set up a small café during the 1990s. A couple of years ago, it received an upgrade and was turned into a chic restaurant. While renovation was underway, a chance discovery became its most defining architectural feature: the exposed stone-work. Workers peeled off layers of plaster and the rather awful contemporary paintings you usually see in all ‘heritage’ spaces in Rajasthan, revealing historical rubble masonry with lime mortar that form neat arches.

When in the desert, create an oasis: cross over to an air-conditioned hall over a delicate bridge over a pond abound with fish, hyacinths, lotus, and other aquatic plants. In an abundantly decorated palace, impose minimalist clean lines, chevron patterns, and a cool, international aesthetic. The memories of a store, or even a vibrant bazaar, are wiped out; the parades and swarms of people don’t need accoutrements but appetisers ― shopping happens in other places.

The contemporary now co-exists with a 200-year-old construction. Tradition peeks through though: a glint of the mirrorwork, a stray brass accent. If architecture is making a case for fusion, so is the food: try a mozzarella kachori, while you’re here.

Aparna Andhare is a curator at a museum in Jaipur and spends all her money on books and coffee. She tweets @a_appy and is on Instagram as @brattybaisaa.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.