I was first introduced to the lanes of Lutyens’ Delhi in December 2019, while visiting my aunt and uncle over Christmas. On this short trip, we went on strolls along the circumference of central Delhi, around India Gate, and through the avenues of Lodhi Road, Amrita Shergil Marg, Tughlaq Road, Copernicus Marg and more. I went back home to Chennai soon after, but I promised myself I’d come back another time and experience these lanes more intimately — and I did. I spent the summer of 2023 at Teen Murti Marg, getting to know its extended area the best way I knew how to — on long walks.

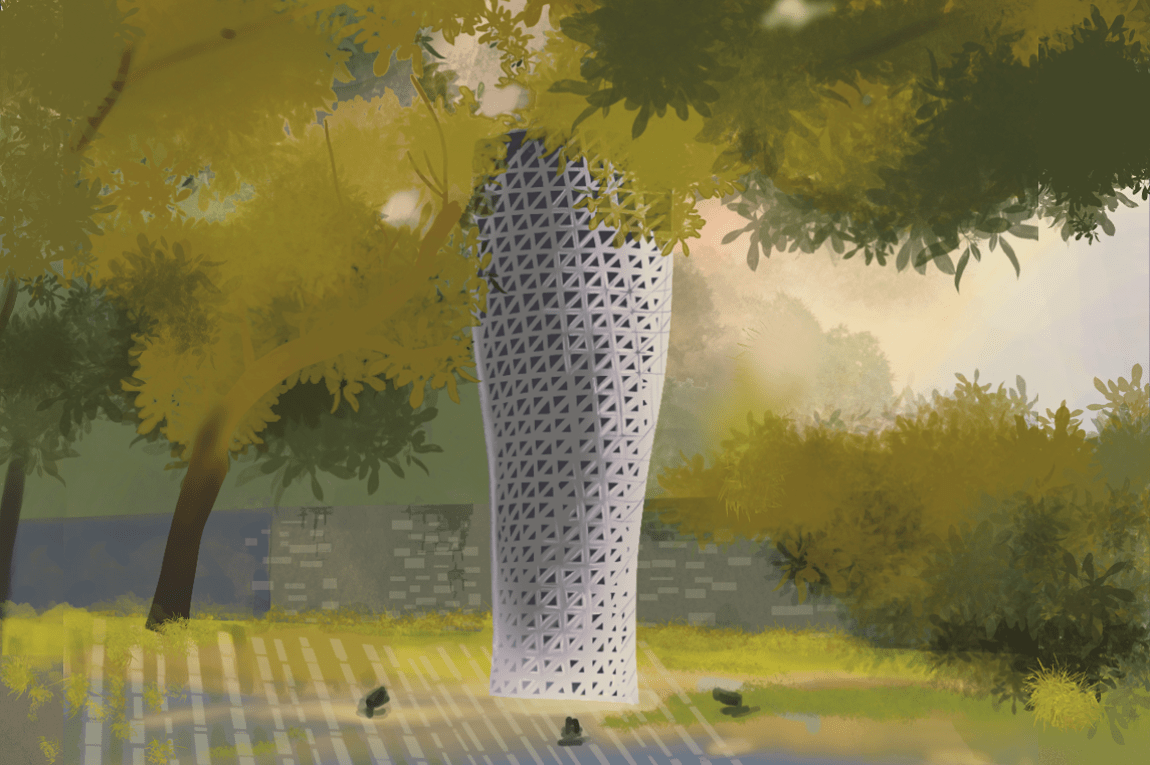

The administrative buildings and bungalows of Lutyens’ Delhi have histories of their own. But I was interested in another facet of this area — its urban plan. While walking around, I couldn’t help but be cognisant of the roundabout-like nature of most roads, and how so many roads were characterised by their trees. The master plan for the area, spanning 26 sqkm, was prepared by the famous British architect, Sir Edwin Lutyens, alongside architect Herbert Baker and Chairman of the Town Planning Committee, Captain George Swinton, after the Raj decided to move its capital from Calcutta to Delhi in 1911. When it was finally inaugurated in 1931, the city proved to be a mix of Indian and European sensibilities, both in terms of its architecture and layout, with landscaped gardens, parks dotted with historic structures, avenues shaded by tree canopies, scenic vistas and watercourses.

It’s said that, initially, Lutyens planned the city as a grid, but that Charles Hardinge, the British Viceroy from 1910–1916, instead pushed for more roundabouts, hedges and trees as measures to break the force of the seasonal sandstorms in the region. These roundabouts sprout from triangular or hexagonal avenues and vistas, while the plan maintains an axial, symmetrical approach. I’ve observed roundabouts with gardens in the centre, blooming with chrysanthemums, daisies, champacas, gomphrena, hibiscus, varieties of jasmine, periwinkles and more.

Lutyens, who was unfamiliar with India’s indigenous trees, had sought the assistance of landscape designer William Robert Mustoe, and embarked on a plantation exercise to create a ‘garden city’, a popular theme for city-planning in the early 20th century. Together, they selected tree species that would line the new roads and principal avenues. Planting started in 1919, and was completed in 1925. Many of the trees planted still stand, although several old trees transplanted due to the central vista redevelopment reportedly did not survive.

Lutyens and Mustoe planted a mix of imported and indigenous trees across more than 40 roads and streets. Avenues that led to prominent structures had the grandest trees, while others — like those where officers lived — had less-imposing trees. Pradip Krishen, a naturalist and author of the book Trees of Delhi, says in an interview with The Indian Express, “They wanted to choose particular trees that they thought would be exactly the right size and shape to ‘frame’ monuments or other features that could be seen at the ends of these roads.” This is likely why the planners restricted large, spreading trees like the laurel fig or banyan trees to big roundabouts. Krishen also deduces that the selected tree species had to be evergreen, uncommon and the correct size for their respective avenues.

The pair finally arrived at 13 species, the size of which would be suited to the width of the avenues, allowing unobstructed views of monuments like the Purana Qila, the Lodi tombs and Safdarjung’s tomb. But in his book, Krishen explains, “If you discount a few species planted sparingly only along single avenues, there are only eight kinds of trees repeated like handblock motifs.” These species — namely jamun, neem, arjun, imli, sausage tree, baheda, pilkhan and peepal — dominated the main avenues. Less common varieties, like mahua, putranjiva, jadi and river red gum were laid along the single avenues. Others — like khirni, ulloo, Buddha’s coconut, anjan and laurel fig — were scattered across avenues that were not planted purely with any one species.

I’ve found that the avenues I spent my summer walking along aren’t simply roads constructed for transport, they have distinct botanical identities that hold meaning for Delhi’s residents, and for me.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Neeraja Srinivasan is currently studying English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University. She is on Instagram at @neerajaaaaaa.

Menty Jamir is a Naga photo-artist based out of New Delhi. She works on long-term personal projects besides being a part of 8:30, an emerging women artists collective in India. She is on Instagram @menty___jamir.