One of my earliest memories growing up in Chennai in the 1970s in a large home with my grandparents, is of evenings spent with my grandmother after a light dinner, lying on the thinnai — a raised porch of polished red oxide in front of the home — listening to stories from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, until I would fall asleep. It was a place that received ample breeze — akin to being in the open — and yet was sheltered from the elements. Every typical Tamilian home (as well as those across the warmer regions of southern India) used to have a thinnai that ran along the outer perimeter — a shaded verandah or sit-out area with built-in seating, usually at the entrance. This was where residents would catch up with neighbours, debate, read, or just take a short nap.

It was where my grandfather’s acquaintances would have a glass of water or buttermilk offered by my grandmother, as they chatted with him. It was an in-between space that not only facilitated social interactions but also protected the entrance of the house from the harsh sunlight. During the 18th century, as British military engineers built or altered existing bungalows so as to accommodate wraparound verandahs, thinnais slowly started disappearing. In turn, the spaces lost out on community interactions and a view of the streetscape.

In a research paper published in 2020, Chennai-based architect Anjali Sadanand refers to the thinnai as a “transition space” between two realms, a manifestation of our socio-cultural nature. The presence of the thinnai does away with the abrupt transition from the exterior to the interior, from the public to the private, especially in villages and small towns in southern India.

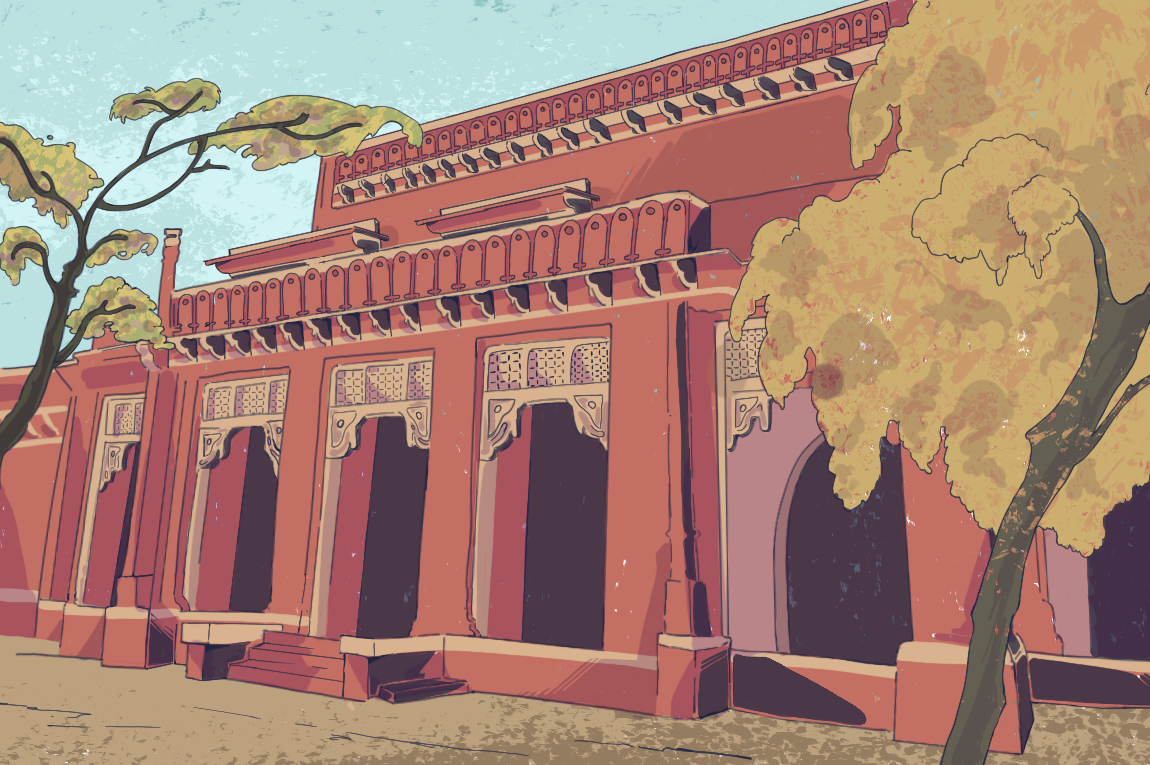

Traditionally, a thinnai is a raised platform running along the entire front of the house, with wooden or stone pillars to support it. There are, however, examples of pillars comprising both a stone plinth and wood. The thinnai was an apt perch to enjoy a cup of coffee at or watch the rain from. Women would stop passers-by for snatches of conversation, or ask hawkers to unload their wares. In our current, fast-paced lives, this traditional space and the interactions it engendered have gradually eroded.

“The thinnai was usually made of the same material as the floor, like stone, cement, lime plaster, red oxide or raw granite and seamlessly wrapped around the house. In the deep south, thinnais were pared down, wherein platforms were made out of cement, and the walls painted in the auspicious colours of red and white. The wealthier parts of Tamil Nadu, such as Chettinad, had tiled floors and ornate thinnais,” shares Chennai-based architect Sujatha Shankar. Moreover, there are variations of the thinnai across the country, known by their local names, such as the otla, commonly found in the pols in Gujarat.

Even today, if you walk through the narrow lanes of Triplicane or Mylapore, the traditional neighbourhoods of Chennai, you will see a few houses with thinnais from the 1950s or the 60s, where residents still sit on the raised platform. You may catch sight of everyday scenes like a mother combing her daughter’s long hair, or an old man reading the newspaper in the morning sunlight.

With references in Tamil literature and popular culture, the multi-functional thinnai has gradually been lost to the pressures of shortage of space, the desire for privacy and concerns surrounding safety. Additionally, newer constructions are, more often than not, individual, isolated dwelling units instead of a continuous block of row houses that would otherwise be part of a community. Nevertheless, the thinnai still lingers in my mind as a quintessential space that forged and facilitated social interactions, harking back to slow-paced, relaxed ways of the past.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Kalpana Sunder is an independent journalist based in Chennai. She is on Instagram at @travelwithkalpana.