Hyderabad has always been a second home for me — it’s where my mother’s family traces its roots to, and as both an avid history buff and a conservation architect, I’ve visited Golconda Fort several times. But it was a unique opportunity to work with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture in Hyderabad that led me to enter a roughly 100-acre urban necropolis: the Qutb Shahi Heritage Park, or as locals call it, saat gumbaz (seven tombs). This is one of the rare vast, ancient cemeteries where nearly a whole dynasty is buried at one location. This is the Qutb Shahi dynasty, seven generations of which ruled in the Deccan between 1518 CE and 1687 CE, before the Mughals took over. What makes it unique to me is that this complex is home to several architectural styles, ranging from Bahmani with Persian influences to a unique Qutb Shahi style that blends local Hindu architectural characteristics with Bahmani features.

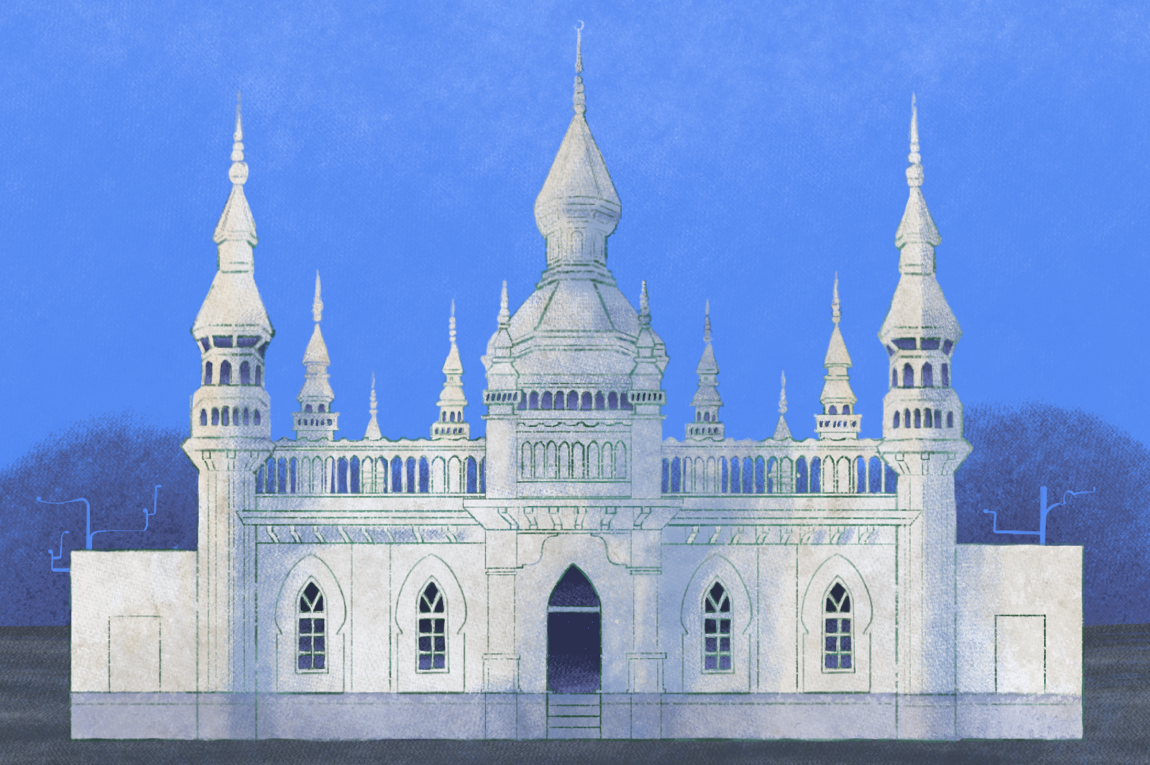

The complex contains over 40 mausoleums, including one with an accessible crypt and another that is said to have been covered in glazed blue and green tiles. There are also 23 funerary mosques, six stepwells or baolis, a hammam, and the remains of what is often referred to as a ‘summer palace’. There’s a gateway that would have connected to the nearby Golconda Fort via the Patancheru Darwaza, archaeological remnants of enclosure walls, and an idgah — an open-air enclosure for Eid prayers — that is still in use. The complex houses several varieties of trees and plants — at least 72 species were identified during an initial survey — as well as a host of bird species.

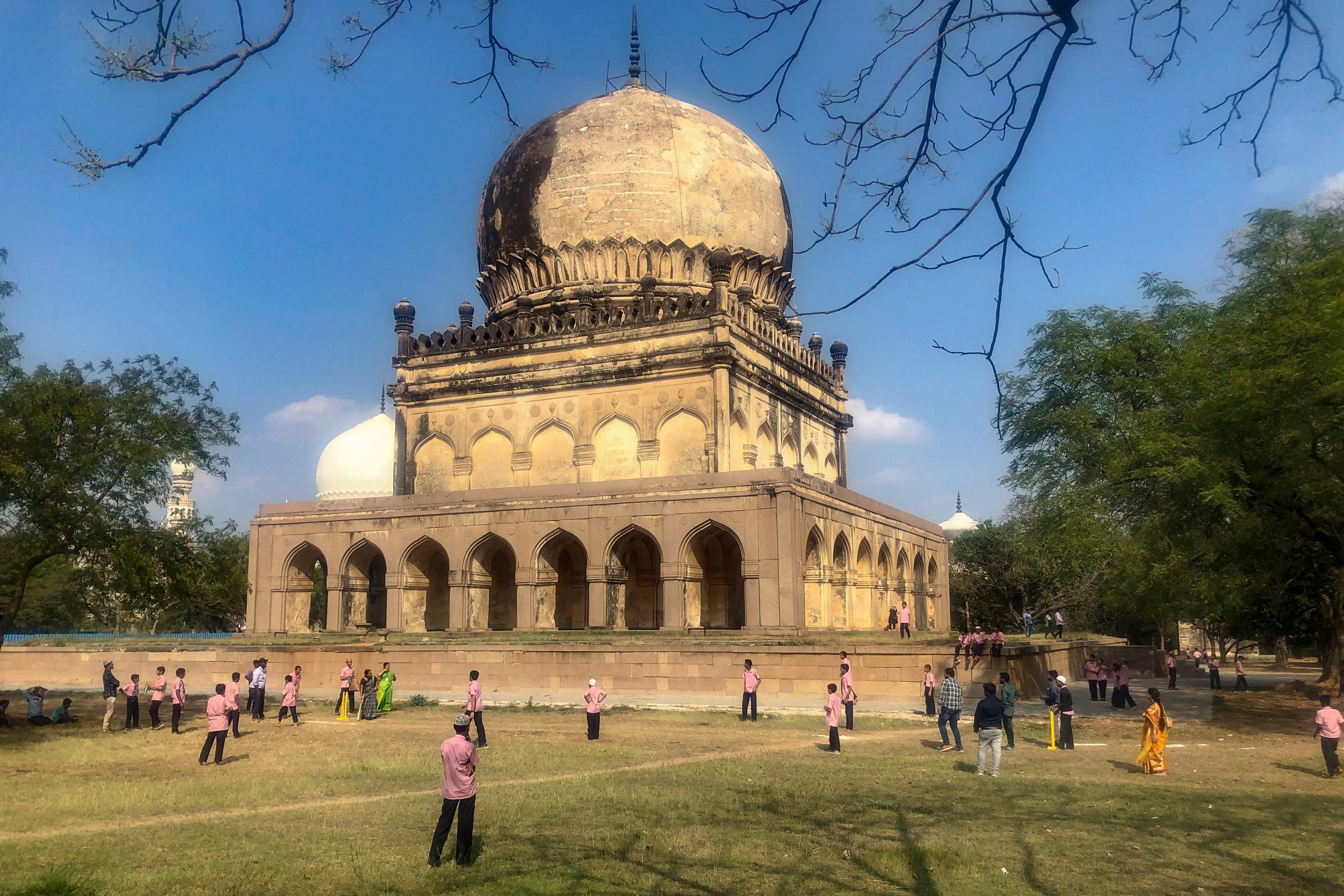

Many structures here were constructed during the lifetimes of the people buried within, and so, reveal some information about the state of the empire under their reign. The mausoleums located in the innermost portion of the park were built for rulers who reigned between 1518 and 1580. These tombs were typically square in plan and capped by a dome, with intricate lime-stucco work and blind arches flanking the doorways on the external facade. They include what is believed to be the second ruler, Jamshed Quli Qutb Shah’s octagonal, two-storeyed tomb, and two shared-plinth mausoleums — those of Sultan Quli Qutb Shah, who established Qutb Shahi rule, and his grandson Subhan Quli whose reign started and ended in 1550.

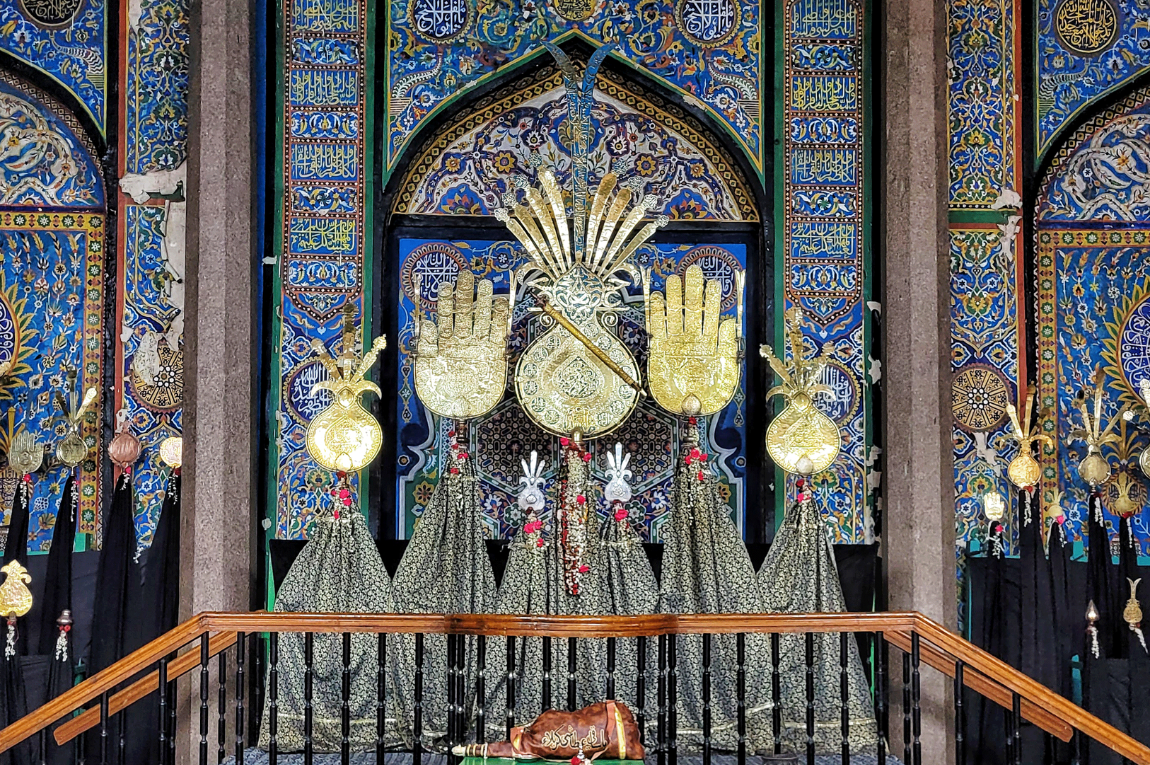

The last two are distinctively Bahmani in style, owing to the style of stucco work. But the neighbouring mausoleum of the fourth sultan, Ibrahim Quli Qutb Shah, is where the architecture deviates from the pre-existing style: This is where glazed tilework, comparable to that found in Samarkand in Uzbekistan, first appears on the facade. In comparison, the earlier mausoleums were solely painted with natural colours to tint the lime stucco.

I found that the mausoleums gradually increased in size, decoration and scale beyond this point, possibly because of the better availability of materials, skilled labour and advanced building methods in a growing empire.

The mausoleums of the sultans who ruled between 1580 and 1625 date back to when the Qutb Shahi empire reached its zenith. These include the mausoleums of Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah — the fifth sultan and founder of the city of Hyderabad — and his successor, Muhammad Qutb Shah. Around the latter are the mausoleums of Hayat Bakshi Begum — Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah’s daughter, who was considered the first lady of the empire — as well as those of Taramati and Premamati, believed to be two high-ranking singers–dancers in the court, the twin mausoleums of the hakims (physicians), and the mausoleum of the commander, among others. The last three, I observed, were smaller than the park’s main mausoleums, but lavishly adorned with lime stucco.

By this time, there is a clear and distinct architectural language that is truly independent of its Bahmani roots, mainly owing to the detail of the stucco work. I noticed that the stucco pieces showing squirrels, fish, floral details, parakeets and other birds — and even Hindu architectural features like the rudraksh and the lotus flower — were articulated differently in the mausoleums that came up after the first generation. This is a departure from the geometric patterns typically used for decoration in Islamic architecture.

Finally, there is the mausoleum of the seventh sultan, Abdullah Qutb Shah, and across it, the unfinished tomb of the last sultan of the dynasty, Abul Hasan Tana Shah, which seems to symbolise the empire’s slow decline.

From a conservation architect and urban planner’s perspective, as Hyderabad expands, the presence of such green urban parks with a repository of monuments is absolutely crucial, not only because they act as lungs for the metropolis, but also because they tell us the story of how the city came to be.

Find your way to the Qutb Shahi Heritage Park in Hyderabad via Google Maps here.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Neha Tambe is a conservation architect and urban planner, with a keen focus on urban conservation projects. She loves discovering what makes cities tick. She is on Instagram at @girlwithoutthechasma.