Every time I walk through a town, I hear whispers from its windows, as if they are holding secrets of the past within themselves. Almost a decade ago, I was walking through the colourful, labyrinthine lanes of Sidhpur, a small town in north Gujarat — roughly 100km from Ahmedabad — to study the havelis as part of a research project for my Bachelor’s in Architecture. As I was documenting the town, its eclectic design and architectural grammar, I started looking for the story behind the protruding windows on the majestic facades of its havelis. Located in settlements called Bohrawads, the havelis were once home to a prosperous community of merchants and traders — the Dawoodi Bohras, whose presence in Sidhpur, by one account, dates back to the 16th century but who have now largely moved away, leaving the havelis vacant.

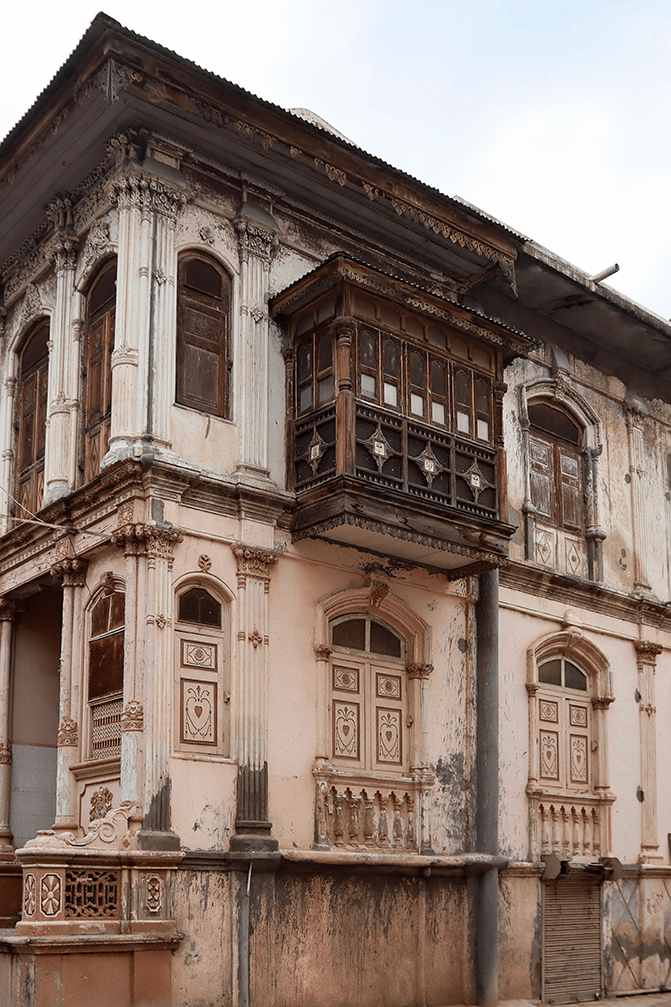

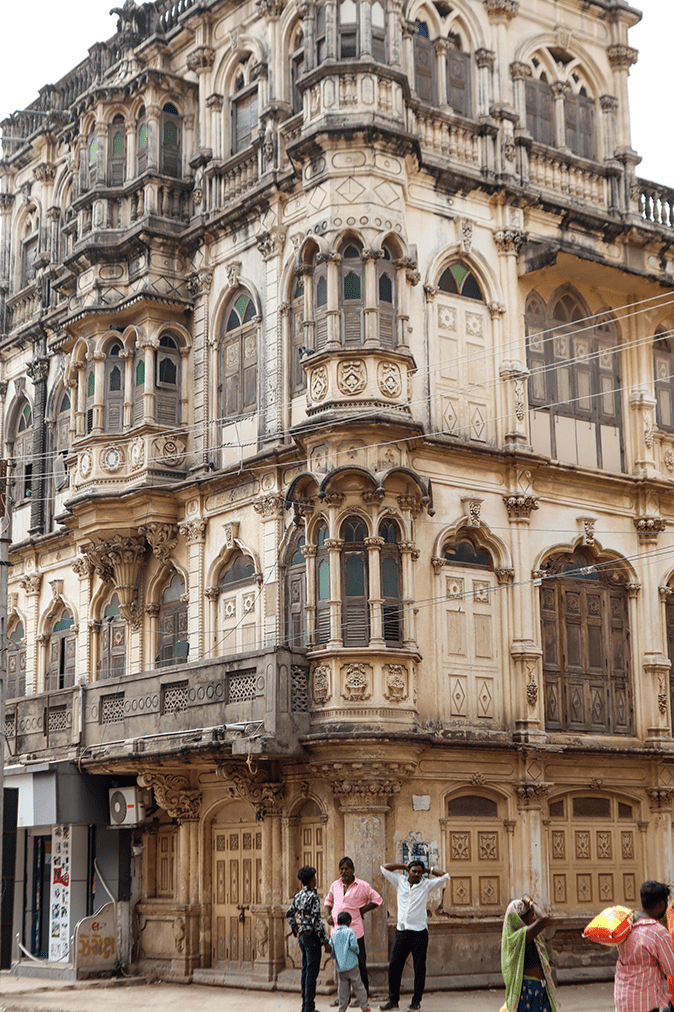

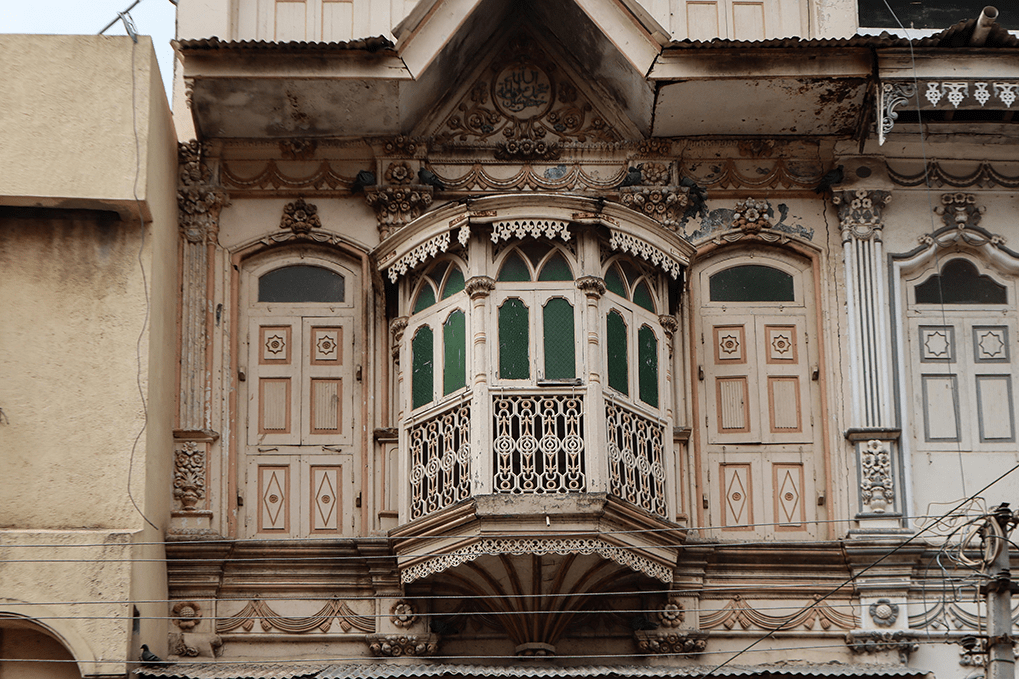

I observed the evolution of the havelis and the movement of the Bohra settlement from the Juni Bohrawad to the Navi Bohrawad, from the old to the new town. The havelis of the Navi Bohrawad were made with extravagant materials sourced from Europe and showed fine craftsmanship. But along the main roads and some side streets — near the Muhammad Ali Tower and in Ashrafpura, Saifeepura and Islampura areas — were windows projecting from the pastel-hued facades. These facades also featured pointed gables, intricate friezes and cornices, stucco work, floral and geometric motifs, wood carvings, columns and pilasters.

At first glance, the windows resembled jharokhas, but a closer look revealed diverse architectural styles, much like the havelis themselves. In the late-19th and early-20th centuries, the advent of railways in the region allowed the Bohras to thrive despite successive famines and extend their help to other local communities. This led to the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad, gifting them a tract of land in Najampura, Sidhpur, to address their housing shortage. The Bohras further expanded their trade in other parts of India and the world. Their travels inspired them to build havelis back home — on the land that was gifted to them — that combined vernacular architecture with European, Art Deco, Italian Baroque and Neoclassical styles.

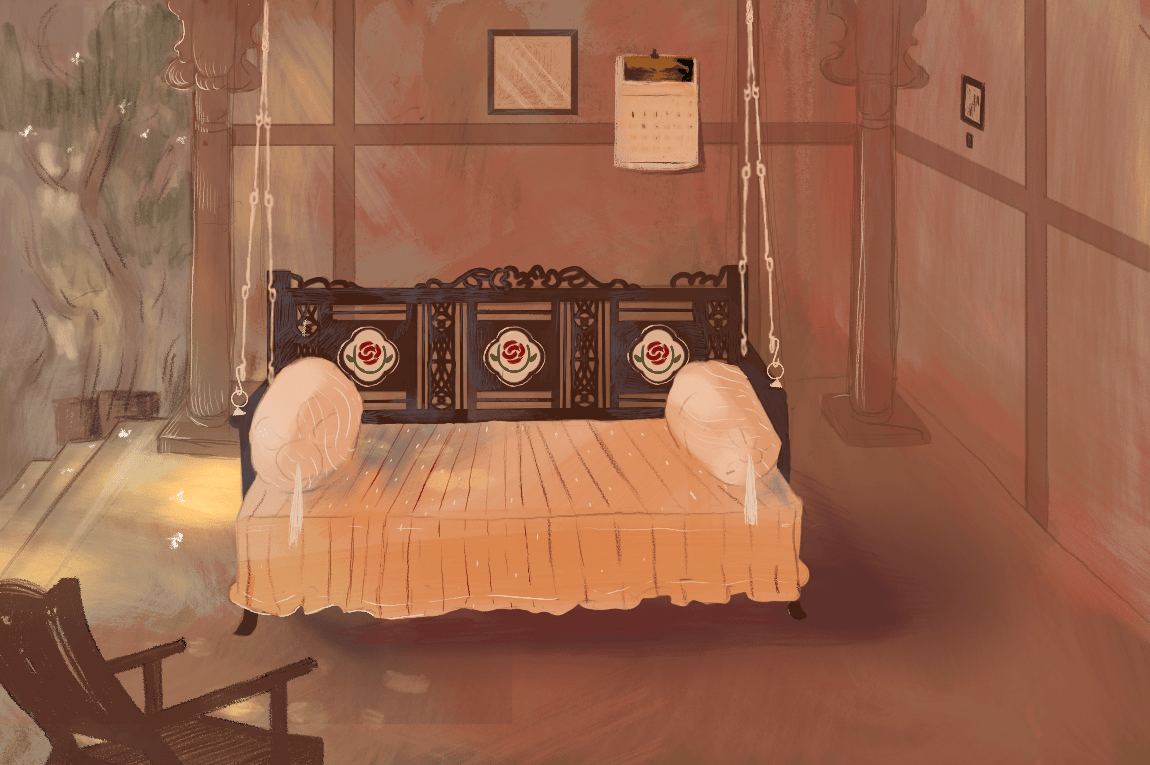

Walking through the inner lanes, I observed that the windows in earlier constructions didn’t protrude from the facades, while the bay windows at the corners of the streets and in the main bazaars were more opulent. These windows, through which the women in the zenana quarters could get a good view of the streetscape, were adorned with European floral motifs carved in marble, had stucco work and stained glass, and were furnished with Burma teak. I could see an amalgamation of elements of French and Gothic architecture, among other styles..

This hybrid domestic architecture is on full display in the Navi Bohrawad, where the carved brackets of the old town are replaced by Corinthian columns, and the jharokhas by bay windows. The windows show the transition — I can make out features of Neo-Renaissance architecture, Baroque and Rococo styles present in various combinations, sometimes infused with Art Deco elements.

In my conversations with the locals, I was told that the new Bohra settlement, built during a period when the community was prospering tremendously, was more of a planned project where 350 havelis were built in a symmetrical balance with repetition and multiplication of elements. The ornamentation, spatial and stylistic features of these curved balcony windows with decorative surfaces add to the grandeur of the havelis and are symbols of an era of extravagance. The windows changed the architecture of the town and now add a certain nostalgia to the landscape.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Dhara Mayavat is an art historian with an interest in Indian architecture. She has been working with several museums and institutions in Gujarat in the realms of curation, archiving, and heritage documentation. She is on Instagram at @dhara_mayavat.