Having recently moved to quiet and sleepy Hyderabad from the excessively stimulating, unsleeping Mumbai, I’ve struggled to find its vein and beat, and therefore my own place in it. Falling headfirst into the trope of how ‘Bombay’ people cannot live anywhere else, I’ve felt consistently underwhelmed by my new city’s offerings.

What I did find aplenty though was history, through a small coterie of people who are actively unearthing buried stories of the city to engage with and keep alive. Hyderabad is teeming with scholars of Deccan Sultanate history, like oral historian and journalist Yunus Lasania, whose walks through old Hyderabad introduce many recent entrants of the city, like myself, to this otherwise cocooned precinct. One of these walks led us to an otherwise unheard-of ashoorkhana, a place of mourning commissioned and historically used by the Hyderabadi royal family. An ashoorkhana is a public space for Shia Muslims to gather on Muharram and mourn the martyrdom of Imam Hussain, the grandson of Prophet Muhammed, in the battle of Karbala.

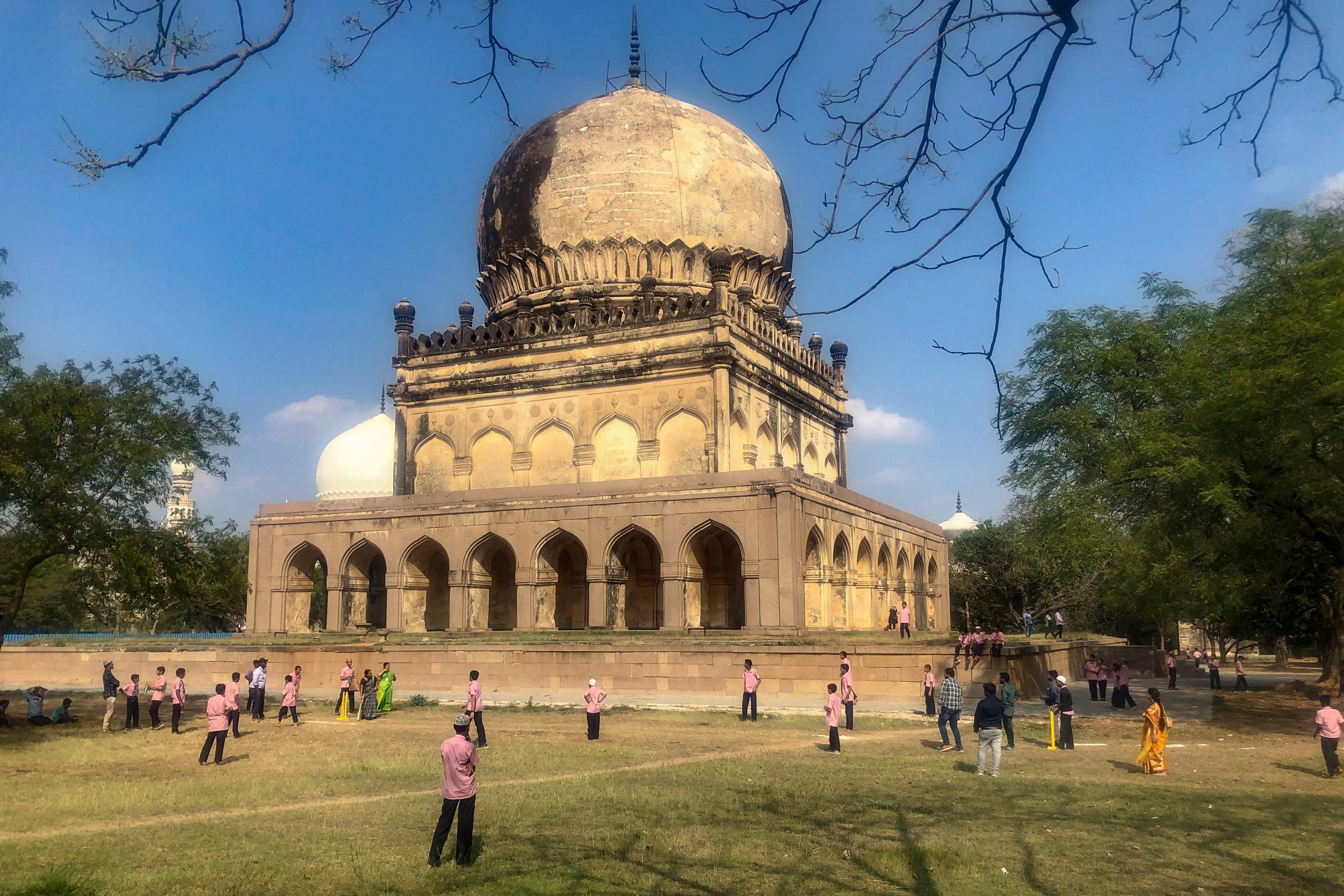

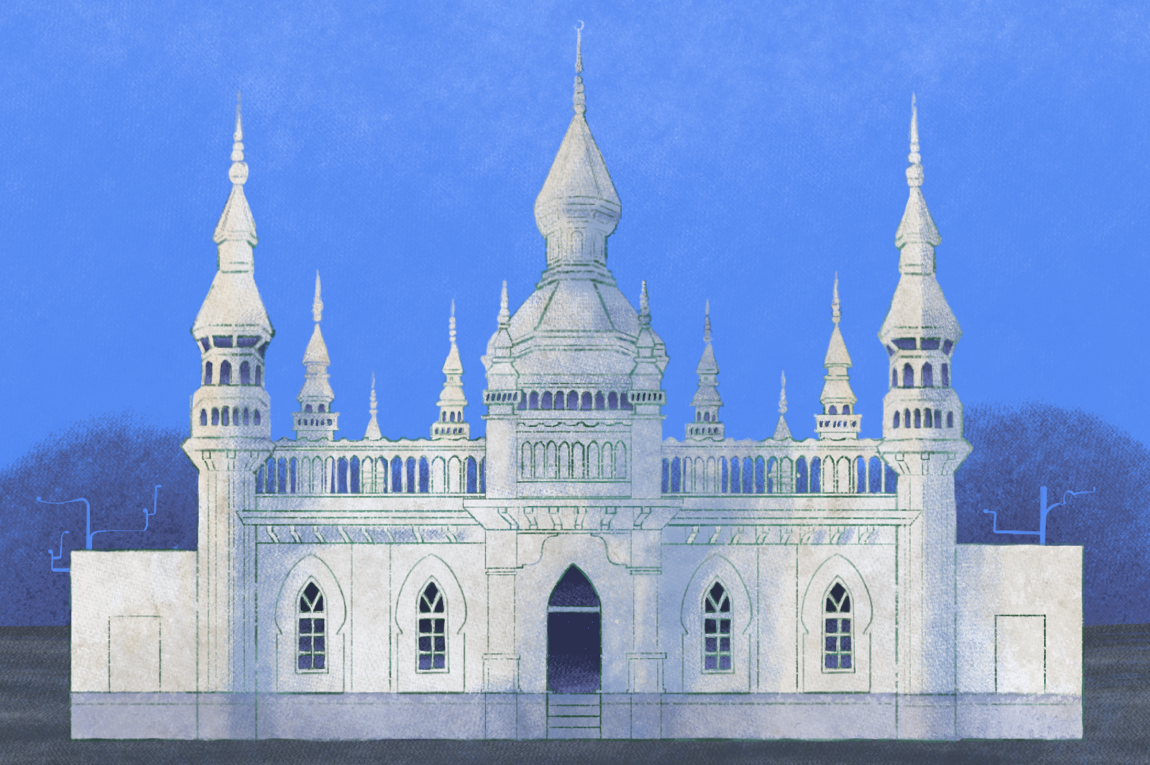

Often overlooked for the grander, majestic minarets of the Charminar and the onion domes of the Qutb Shahi tombs, the Badshahi Ashoorkhana (literally the Royal House of Mourning) is a delicious slice of history, hiding in plain sight. Built by Sultan Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah of Golconda around 1594, soon after the Charminar was erected as part of the city’s foundation, the ashoorkhana is a protected heritage site and among the oldest imambaras in India.

The ashoorkhana forms part of a complex of various structures, including the naqqar khana (drum house) where the traditional naubat was played; the sarai khana, a place of rest; and the niyaz khana, langar khana and abadar khana for distribution of refreshments or tabaruk. All of these structures are now in various stages of dilapidation, neglect and disuse.

From a distance, the inside of the ashoorkhana seemed to be a decrepit, unassuming structure with what looked like crumbling coloured wallpaper. But a closer look revealed that the crumbling wallpaper was, in fact, enamelled mosaic tiles inlaid in ingenious Islamic-style patterns, which have covered the ashoorkhana’s interior walls since 1611. Created in haft-rang (seven colours) mainly with lapis blue and white tiles, the mosaic is exquisitely lain with Indian tones of mustard yellow, warm terracotta and vibrant green, forming incredible patterns that depict Shia Muslim symbology and are linked to the battle of Karbala. As art historians George Michell and Mark Zebrowski point out in their book Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates, this is one of the most original decorative schemes of its kind anywhere in the Muslim world and has survived in stellar condition for over four centuries. The Qutb Shahis of Golconda were said to be the ultimate Deccani patrons of tilework and like their Turkish ancestors, were fervent Shias.

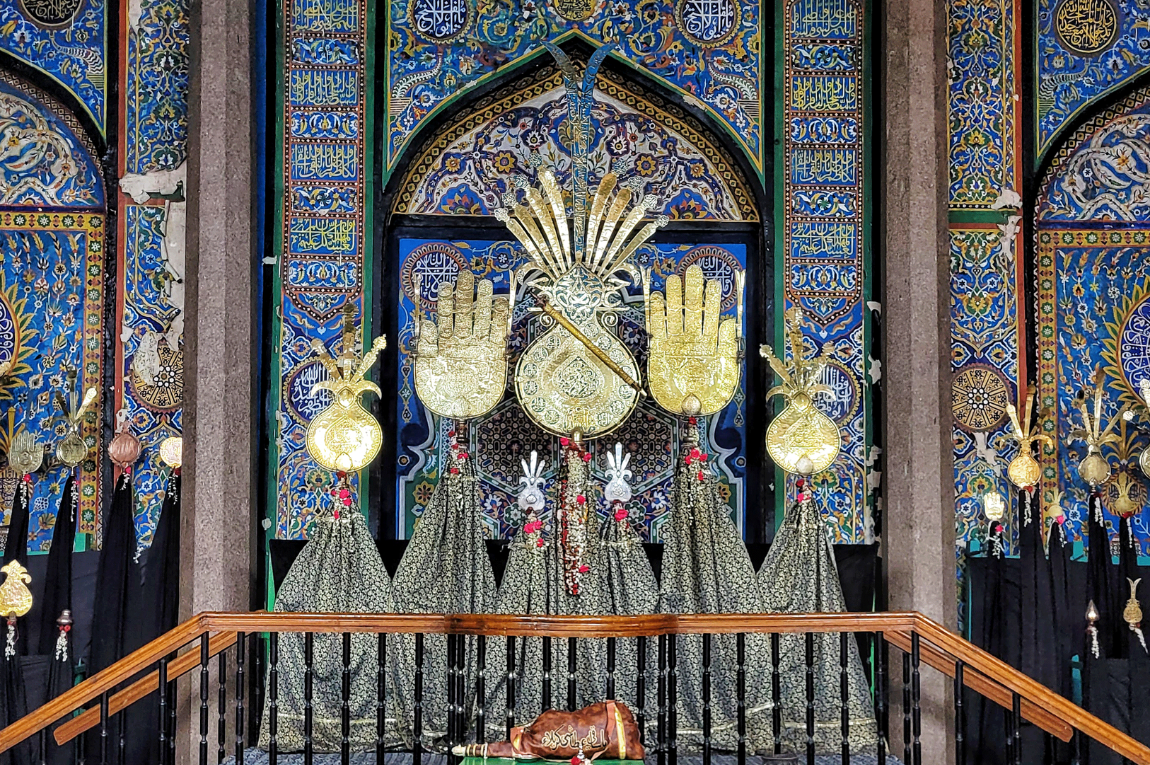

The tiles, arranged in large panels — almost 3 metres high and over a metre wide — had us craning our necks to decode the intricate artistry of the medieval Islamic civilisation of the Deccan. One of these represents a large calligraphic alam — a religious metal standard (akin to a banner) that symbolises those carried by Hussain and his followers in battle — which features bold, exquisite Arabic script, both right side round and mirror-reversed.

Along the adjacent walls lie staggered mosaic hexagons connected by arabesque swirls, and a panel showcasing what’s referred to as the ‘pot of plenty’ with flowers and vegetation emanating from a vase. To my eyes, it also seems to visually represent the overarching theme of the alam and the ashoorkhana being enduring symbols of remembrance.

The royal chronicles of the Qutb Shahi era mention tangible gold alams studded with jewels, but these no longer exist. Nevertheless, impressive brass alams decorated with fine Thuluth script, which post-date the Qutb Shahi period, are now brought out and installed only during the holy month of Muharram.

After the fall of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, the ashoorkhana was even used as a bandi khana (carriage shed) during Aurangzeb’s reign. Later, the Musi River floods of 1908 that wreaked havoc on much of the city also flooded the ashoorkhana premises, damaging part of the mosaic, which has since been hand-painted as a fresco.

As per news reports, the caretaker of the ashoorkhana, Mir Abbas Ali Moosavi has been struggling with renovations to the premises due to political interference. But perhaps what is most crucial to preserving the cultural fabric of cities like Hyderabad is an awareness — often supported by the research of historians like Lasania and his community of brimming academics — of the narratives, art history and architecture that is all around us, coaxing us to seek beauty in structures long-forgotten.

Find your way to the Badshahi Ashoorkhana in Hyderabad via Google Maps here.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Amrita Amesur is a corporate lawyer who has spent the last few years dedicatedly studying and documenting her family’s food experiences, while learning to develop her own voice as a cook and a writer. Her essays on food and culture have been featured on Goya Journal, Whetstone Magazine and The Huffington Post, amongst others. She is on Instagram at @amritaamesur.