The Chettinad region, spread over the Sivaganga and Pudukkottai districts of Tamil Nadu, is well-known for its opulent architecture and town planning. As an architect and a frequent visitor to the region, I’m acutely aware of the diverse material culture that contributed to the construction of the eponymous mansions, built in the Madras Presidency during the 19th and 20th centuries.

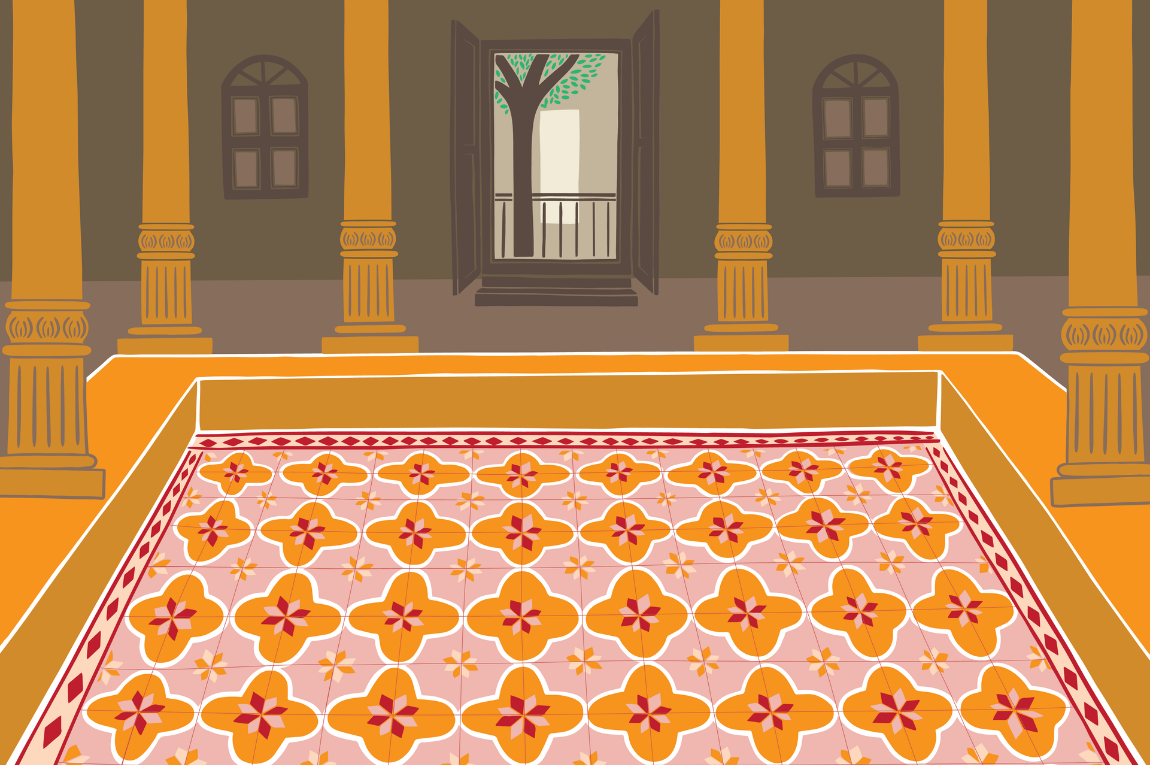

All my life, at our ancestral house in Karaikudi, I have observed the local and imported treasures — the Athangudi tiles, Burma teak, and Italian marble. However, it’s upon my visits to the palatial homes of relatives for weddings and other occasions that I’ve spotted stained glass in vibrant tones of red, yellow, blue, green — and even in white — adorning the windows of the facade, the hallways, and sometimes, the arches flanking the foyer. The elders of my family, who have travelled to various South Asian countries for trade, are quick to point out that the glass was imported from Belgium. One can spot the glass by looking closely at some of these mansions while walking through the streets of Karaikudi, Kanadukathan, Athangudi and other Chettinad villages of Tamil Nadu.

My curiosity piqued, I ventured to find out more. There was evidence of local glass beads and bangles industries in southern India, but no records of window panel manufacturers until the early 20th century, which is when industrial glass production in India started. During the Gothic Revival movement that lasted throughout the 19th century, medieval-inspired stained glass started to appear in churches, civic, institutional, and domestic buildings in Europe, and consequently, in India. The Chettinad mansions are believed to have been built between 1850 and 1950, which coincides with this period in history.

My Chettinad ancestors were venture capitalists who travelled extensively to other South Asian colonies in the early 19th century. They gathered experiences, knowledge and architectural influences of foreign countries, and this acquired wealth reflected in the domestic architecture back in their hometowns.

I’ve often found glassware, such as coloured lanterns, bowls, tumblers, wristwatches, etc., with ‘made in Belgium’ labels in our home and wondered at my ancestors’ interest in Belgian products. This led me to read about Belgium’s independence from the Netherlands in 1830 and the country’s glass-manufacturing prowess. The Belgian window glass industry grew spectacularly during the 19th century, when about 90 to 95 per cent of the production was exported across the world, except to France and Russia. Relations between India and Netherlands existed since the 17th century, when the Dutch East India Company established spice and textile trade with India. The Dutch were present in parts of India until the early 19th century. Subsequently, glassware distributors for popular Belgian companies like Val Saint Lambert in 1826 were also present in Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta.

That is when I connected the dots and came to believe that glass imports from Belgium were used for constructing many of the more opulent Chettinad houses, in the windows and decorative arches.

The stained glass I’ve observed covers various degrees of the windows at different houses. In some places, I noticed that the four large openable panels of the windows are divided into six smaller parts, each entirely covered with square stained glass using timber frames. Sometimes, I’ve found smaller stained-glass panels fixed over the windows that have common wooden panels. I’ve seen them in primary and secondary colours, with iron grills facing the outside. These panels are primarily square and rectangular, but in some houses, they remind me of pointed gothic arches. Apparently, stained glass was present across India during the colonial period, which could partly be attributed to British architect–engineers who practised in many parts of the country.

While many Chettinad mansions have now been brought down, I’ve always found it fascinating to understand the effort that went into building them. This time, it was the sourcing of material as distinct as stained glass from a faraway land like Belgium, and how it subtly displayed the lifestyle of the Chettiars to the world outside their mansions.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Meena Azhagappan is an architect and historian based in Ahmedabad, and loves reading between the lines when it comes to the architectural history of British India. She is on Instagram at @meena_azhagappan.

Diya Paul is a Mumbai-based illustrator. She is on Instagram at @diyapaulart.

Good to see recording the legacy of architectural elegance of Chettinad houses . You as a author imbibed this structural beauty from childhood of course inherited Good luck