Growing up in Chennai in the early 1970s, we took for granted the elegance of the architecture around us — from Indo-Saracenic buildings with their onion domes and jharokha-style windows to Art Deco wonders. My favourite, however, was a semi-circular, candy floss-coloured, two-storeyed Victorian building with classical arches called the Ice House. This extraordinary structure overlooks the Marina Beach, and is now christened Vivekananda House, after Swami Vivekananda’s nine-day visit in 1897 upon his return from Chicago where he delivered the historic speech at the World Parliament of Religions.

The 13-kilometre-long Marina Beach that stretches from Fort St. George to Marina Lighthouse is lined with memorials and statues, and is populated by vendors selling fast food. Sitting on the sandy beach on summer evenings, I would hear stories from my mother and grandmother about how the building was once used to actually store ice, and how later, it served as a home for child widows.

The Ice House owes its name to an ice trade that once flourished between British India and merchants in America, owing to a lack of refrigeration facilities in India. Fredrick Tudor, a Boston-based entrepreneur — known as the ‘Ice King’ — saw potential in shipping large blocks of ice wrapped in sawdust, so as to prevent it from melting, from the frozen lakes of New England. These were loaded on to empty ships to cater to officials of the East India Company, particularly in the humid presidency towns of Madras, Bombay and Calcutta. The ships that brought ice to Madras — as Chennai was known then — carried back goods such as jute, saltpetre, indigo and animal hide to New England. While the British officials preferred their drinks cold in the unrelenting heat, wealthy Indians could also have access to cold beverages in their homes, clubs and restaurants.

Enterprising Tudor was not only involved in shipping the ice but also designed and built insulated buildings across India that could store the ice blocks once they reached the ports. Unfortunately, the Ice House in Chennai is the only one that survived. Functional until about the late 1870s, it still stands tall today.

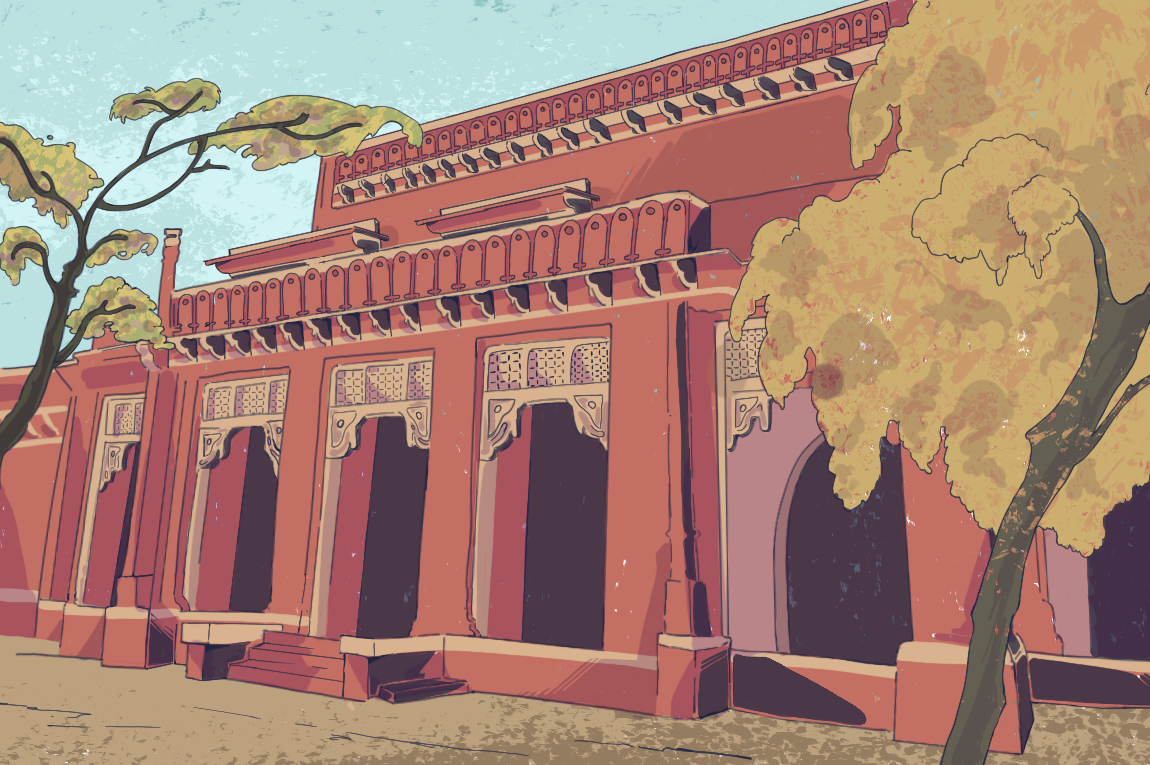

Tudor built the Ice House in 1842, on land that was bought with funds raised by the Anglo-Indian community and leased to him. An underground ramp led up to the beach and a mechanical pulley was used to haul the blocks. With huge arched windows, motifs of sunbursts on the facade, and stately Grecian columns, it quickly became a landmark. By the end of the 19th century, the ice-trade monopoly became redundant as artificial refrigeration facilities began mushrooming in India.

According to S. Muthiah — who has written widely on the British in Madras — the ownership of the Ice House passed to the advocate Biligiri Iyengar in 1880, who re-named it Castle Kernan after his friend and fellow lawyer, Justice Kernan of the Madras High Court. Iyengar converted it into his residence and added circular verandahs for better ventilation. However, given that it was designed as a storage space, it did not make for an ideal place to live.

The building was finally auctioned off after Iyengar’s death in 1906, and bought by the Madras government who made it a home for child widows in 1917 under reformist Sister RS Subbalakshmi. The widows had a pitiable existence, and it was Subbalakshmi’s ambition to make them self-supporting and independent. In the 1940s, the building functioned as a hostel for teachers in training. In 1963, to mark the birth centenary of Vivekananda, the government of Tamil Nadu renamed it as ‘Vivekananda Illam,’ or Vivekananda House.

V. Sriram, Chennai historian and heritage activist, writes on his blog that the construction of the Ice House with its parabolic dome was considered revolutionary back then as the storage of ice demanded that no timber was used — in cold storage, timber would rot. Hence, the British military engineers of the East India Company borrowed a technique from Syria wherein domed structures were built without using wood. Cylinders were constructed out of earth and with the help of a bamboo scaffolding, embedded in lime mortar and layered one on top of the other. This was called the Syrian roof; besides being doubly insulated, it was also resistant to rodent infestation.

My last visit to the Ice House was when it reopened after months of the pandemic-induced lockdowns. It is maintained by the Ramakrishna Math now, and has a museum dedicated to Vivekananda. I looked closely at every detail and marvelled at the structure that had lasted for so many years, and served various functions, yet retained its intrinsic beauty.

Find your way to the Ice House in Chennai, Tamil Nadu via Google Maps here.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Kalpana Sunder is an independent journalist based in Chennai. She is on Instagram at @travelwithkalpana.