I grew up in a Mehrauli mohalla, with houses built next to and sometimes within tombs, narrow streets with cows halting the traffic, tall mandirs and masjids standing across each other, and the occasional swirl of tourists randomly flocking our neighbourhood. On Sundays, my friends and I would play cricket at Zafar Mahal, our favourite spot. Outside the main gate, some older men would be playing cards and smoking cigarettes; at the entrance, a nonchalant security guard would threaten us to finish our game and vacate the complex in time; and inside, in what looked like small caves to me as a child, young couples could be found carving proclamations of their love on the walls.

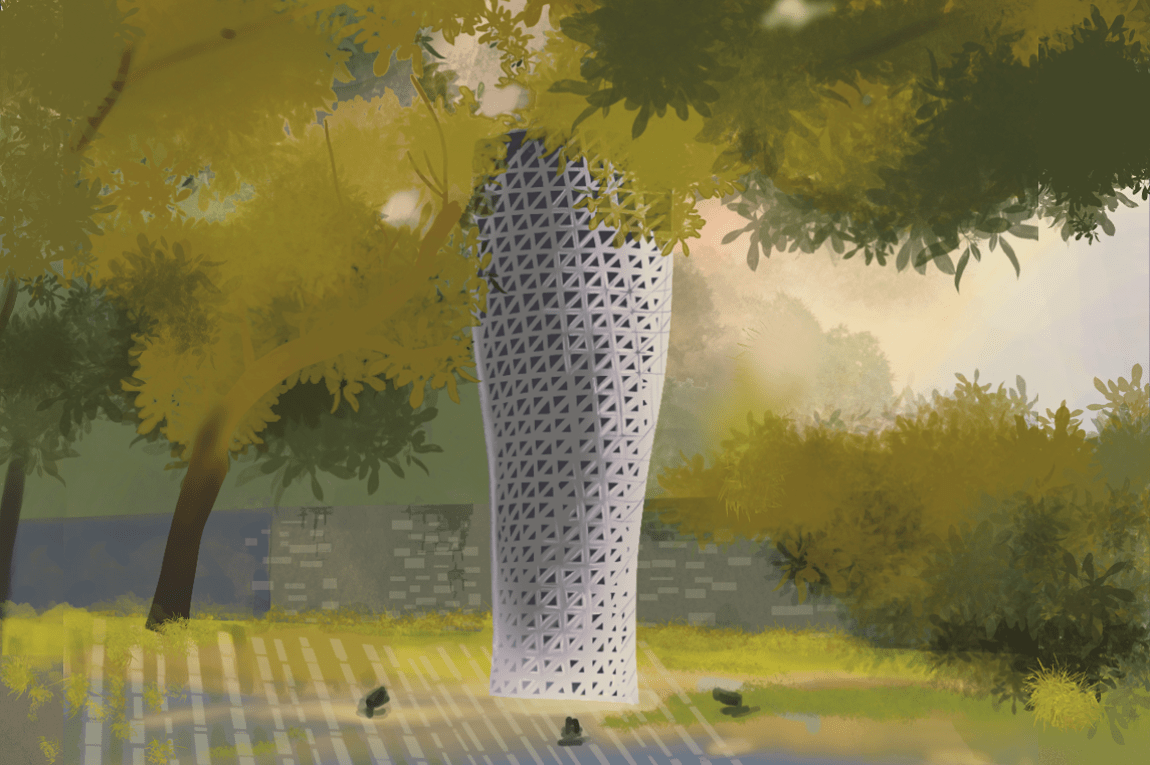

Zafar Mahal, unlike the other opulent Mughal palaces in Delhi, was built during the twilight years of the Mughal era, when the treasury was dwindling rapidly. The relatively shoddy construction — along with negligence by authorities and us, the locals — have left the Mahal in shambles. The oldest structure in the palace complex that stands today is the grey sandstone tomb of Alauddin Masud Shah, the Sultan of Delhi from 1242–1246. Next to the palace is the three-domed Moti Masjid, which was built by Bahadur Shah I between 1707–1712. The palace itself was erected by Akbar Shah II in the early 19th century and then renovated in 1847–48 by Bahadur Shah Zafar II, who reportedly could not afford to build himself another retreat away from his abode in Shahjahanabad, owing to a shortage of funds.

It was Zafar who added the 50-feet tall Hathi Gate — big enough to have allowed elephants to pass through — with a Naubat Khana (drum house), jharokhas covered by sloped Bengali roofs, and an imposing archway with a broad chhajja and a lotus bud at its centre. He’s also the one who named the palace after himself. (Some records mention that it was earlier known as Khas Mahal.) This summer palace in the hilly belt of Mehrauli was a hub of activity for some months of the year, when the court would move here. The emperor would spend his time here hunting, praying, and engaging in private poetry recitals with famed poet Mirza Ghalib. He would culminate his stay with the Sair-e-Gul Faroshan or phool waalon ki sair (procession of the florists) — a fair that started more than two centuries ago and is still held after the monsoon. It is a joyous display of the city’s syncretic culture that I remember desperately waiting for every year throughout my childhood.

The gateway, which resembles those of earlier Mughal forts and palaces, leads to arcades on the south and the east. The interiors now lie largely in ruin owing to the inferior quality of the masonry (as the plaque outside reads), but the layout — said to have been inspired by the Chhatta Chowk (vaulted arcade) of the Red Fort — follows the configuration of space found in later Mughal structures, with dalans (verandahs) and compartments surrounding the court. The use of Mughal design motifs like the monumental gateway, chhatris (domed pavilions) and floral ornamentations, especially on the upper storey, as well as signature building materials like red sandstone and marble, suggests an attempt at reviving the emblematic architectural form. At a time when most prominent constructions in the subcontinent were being built by British architects, this was the emperor’s response to the diminishing political authority of the Mughal dynasty, following the annexation of Delhi in 1803.

Zafar Mahal was built adjoining the dargah of Hazrat Khwaja Quttubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, a 13th-century Sufi saint who was revered by the Mughals. This is likely the reason why three generations of emperors — Bahadur Shah I, Shah Alam II and Akbar Shah II — lie buried next door in a marble enclosure with jaalis, multifoil arches, marble cenotaphs, and a vacant spot at its centre. That spot is where Bahadur Shah Zafar II, the last Mughal emperor, wished to be buried — a wish that remained unfulfilled for he was captured by the British and exiled to Burma. Zafar lamented, and even prophesised, his unfortunate end in a verse he wrote in the final years of his life:

kitnā hai bad-nasīb ‘zafar’ dafn ke liye

do gaz zamīn bhī na milī kū-e-yār meñ

How unlucky is Zafar! For burial,

Even two yards of land were not to be had in the land of my beloved.

It’s strange to think that, had events unfolded differently, his grave might have been a stone’s throw away from my cramped and chaotic mohalla, where Zafar Mahal still stands out quite literally because of its sheer scale. It remains an exemplary artefact of Mughal architecture, despite its dilapidated condition — a swan song that echoes the descent of an empire.

Find your way to the Zafar Mahal in Mehrauli, Delhi via Google Maps here.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Prajesh Kashyap is a Dilliwala at heart who often dabbles in theatre, writing and music. He is on Instagram at @prajeshhh.