Delhi, where the past yokes with the present, is a haven for history enthusiasts like me. I moved here a decade ago, and have often found solace in the lanes of Chandni Chowk in old Delhi. Established by Mughal emperor Shah Jahan between 1639 and 1648 CE on the banks of the Yamuna, and eponymously named Shahjahanabad, it was a planned city, parts of which also developed organically. It was neatly divided into mohallas (neighbourhoods), kunchas (houses surrounding courts) and katras (commercial enclaves) based on occupation and other factors. In my quest of discovering and rediscovering the old city, I ventured on a heritage walk through its havelis.

These courtyard homes were popular in north and northwest India, from roughly the 17th century onwards, and housed familes — sometimes joint, often noble — along with their staff. They had designated spaces for women, men and animals, and often had arched entrances with elaborate doorways. Most havelis were built using lakhori brick masonry, lime and stucco, and red sandstone was used for brackets, columns and slabs. Our guide Abu Sufiyan, who founded the digital community Purane Dilli Walo Ki Baatein, mentioned that the significance of the havelis was reflected by their location, courtyards, interiors and gateways. The level of decoration on the entrances symbolised the status of the occupants.

Over time, the havelis underwent transformation. Some residences of 17th-century nobility were, by the mid-19th century, acquired by a new middle class comprising small traders and merchants who used these as residences, or for manufacturing by turning them into warehouses and shops. Subsequently, several havelis were fragmented by the British as retaliation to the Siege of 1857. Post-independence, an influx of Partition refugees led to many becoming commercial establishments.

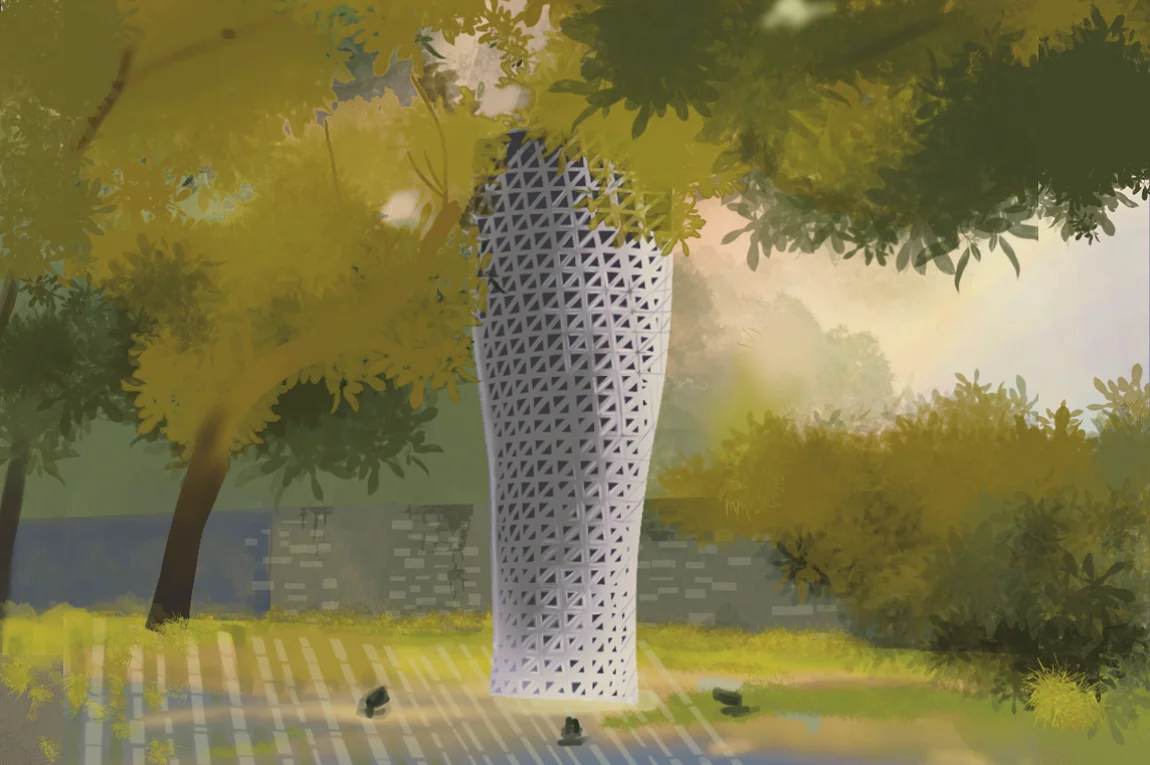

The passage of time also manifested in several architectural changes. I could make out, for instance, that sandstone decorations were covered with layers of paint or cement. In some havelis, the open pavilions around courtyards were made into rooms with wood-panelled doors and stained glass. Elsewhere, there was a shift from jharokhas to colonnaded, wrought-iron balconies, and from brick walls to stone panels or plaster. In places, timber beams were swapped for steel, and Greek columns and cement lattice screens were introduced.

While some havelis have been restored, many are still decaying due to neglect. To me, they are a representation of the city at large — structures of beauty and opulence choking under the weight of urbanisation. And yet, they continue to offer a portal to Delhi’s winding history.

The decoration on the havelis would vary depending on the style in which surrounding buildings were made. For instance, in the Naughara lane where the havelis are said to have housed Jain families, I noticed that some gateways and gokhas had designs inspired by nature — with motifs of vines, plants and birds like peacocks and parrots.

Screened windows, or jaalis, on the upper floors allowed the women of the household to conceal themselves from public view while they watched ceremonies. Sometimes, jharokhas would protrude from the facade, often with the typical nine-cusped ‘Shahjahani’ arches and thin columns separating them.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Parboni Bose is a photographer and writer with an avid interest in culture, history and architecture. She is on Instagram at @monotonesandblurs.

It opens up a totally new field of interest to me. Next ti.e I visit this place I would be curiously searching for these havelis.

Extremely entertaining as well as enlightening read! Bringing a not so interesting topic to LIFE! Keeping the reader engaged till the very last word.