Forty-six-year-old Sarnath Banerjee doesn’t think he makes graphic novels anymore — instead he prefers to call them ‘illuminated texts’, where the drawings create a strong sense of place and atmosphere. Following the recent release of his book ‘Doab Dil’, and his solo exhibition ‘Spectral Times’ in Mumbai, the Berlin-based writer-illustrator talks to us at length about reading, the strange satisfaction of losing, and why the Indian middle class provides the most intriguing fodder for his stories.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I have gone back to reading a lot of Bengali fiction. While English literature has played a role in shaping my imagination, I needed to immerse myself in the works of non-English writers. I keep revisiting Tarasankar Banerjee’s novel Arogyaniketan (1953). It is set in the village of Debipur [in West Bengal] in the 1950s, and revolves around three generations of Ayurveda practitioners, and how the youngest son doesn’t feel the need to study this ancient science. The way in which the themes of healing, disease, and death are tackled is just fascinating.

I also keep going back to the works of Leela Majumdar, a brilliant writer of children’s literature, mainly ghost stories. One doesn’t read her books, one eats them — I’d call it ‘yummy writing’. Bengali literature lends a certain sentience to a narrative. It is purely rooted in nature, so even things that cannot speak seem perceptive.

I also find The City & the City (2009) by China Miéville interesting: it brings together two cities that exist simultaneously, in a complicated, almost dystopian manner. The ideas of borders and nationhood and identity — all very relevant today — are explored here.

In the introduction of your latest graphic novel ‘Doab Dil’ you mention that the book “brings together drawings and text like two converging rivers…the spaces between the text and images form the central backbone of the book.” Could you elaborate on that?

I don’t think I’d call Doab Dil a graphic novel. The language of a graphic novel can get slightly restrictive. All Quiet in Vikaspuri (2016) was perhaps my last graphic novel. I like the free-flowing nature of an illuminated text, like the Shahnameh or even the phad paintings in Rajasthan or the jatra form of theatre. An illuminated text offers you the possibility of a visual reading — the drawings are filled with details, a sense of place and atmosphere is embedded in them. Doab Dil takes its name from the Farsi words ‘do’ (two) and ‘ab’(rivers) — and ‘Doab’ is synonymous with a narrow tract of land between two rivers, particularly the Ganga and the Yamuna. It is then a book about a walk or a romp across time and geography, where civilisations thrive. It is actually an archive of my ‘deep reading’; what I read should become part of my muscle, I feel I should own it.

What are your thoughts on graphic novels without words?

A graphic novel instills words inside your head through visuals. But I think it is radio that is a visual medium. Spectral Times [Banerjee’s ongoing solo exhibition at the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad City Museum, Mumbai] has a number of radio installations, and every listener’s experience, what they imagine or visualise, will be different from mine. I call them ‘radio comics’, which could then be a counter to graphic novels without words. You’re sitting in a semi-dark room, and just surrender yourself to what you hear.

You’ve lived in several cities — New Delhi, Calcutta, London, and Berlin. Do the observations you make or conversations you hear then seep into creating traits for your characters? Do you find intersections among people across these cities?

I live in Berlin but my visual idiom is still very much linked to the Indian middle class and their hidden implications. In India, I could read a person on the train — gauge where they come from, what conversations they might be having. While I’ve lived in cities across Europe, they haven’t really prompted me to draw inspiration from them. I have resisted this throughout. Their histories are overexpressed and overclaimed; you can never confidently say, ‘this is untold’. I belong to a generation of Indians who call themselves ‘Post-West’. The West doesn’t define us anymore. It is neither antagonistic nor alien, we just exist parallel to it. Meanwhile, I am deeply interested in the histories of Chinese, East African, and South Asian societies, in the Global South.

Have you had readers come back and tell you that the characters from your books perhaps remind them of someone they know?

That’s always an occupational hazard! Or then someone will come up to you and say, “I want to be in your next book.” My works have largely been pastiches of several characters, and you might just find aspects of your own personality in one of the characters. For instance, my protagonist [in Doab Dil] Birjis Bahri, a laid-off fact-checker at the daily newspaper Spectral Times, is based on one of my journalist friends, who then went off to the North-East [of India].

You co-founded the comics publishing imprint Phantomville with Anindya Roy back in 2002. Would you do that in 2019?

Definitely, even more so, in fact! There is so much talent around today. With Phantomville, we had to shut shop [in 2008] because we weren’t very good with recovering money. Our books were everywhere but the distributors were tough to deal with. We worked with the print medium closely, especially on collaborative projects between artists and writers, which are very important.

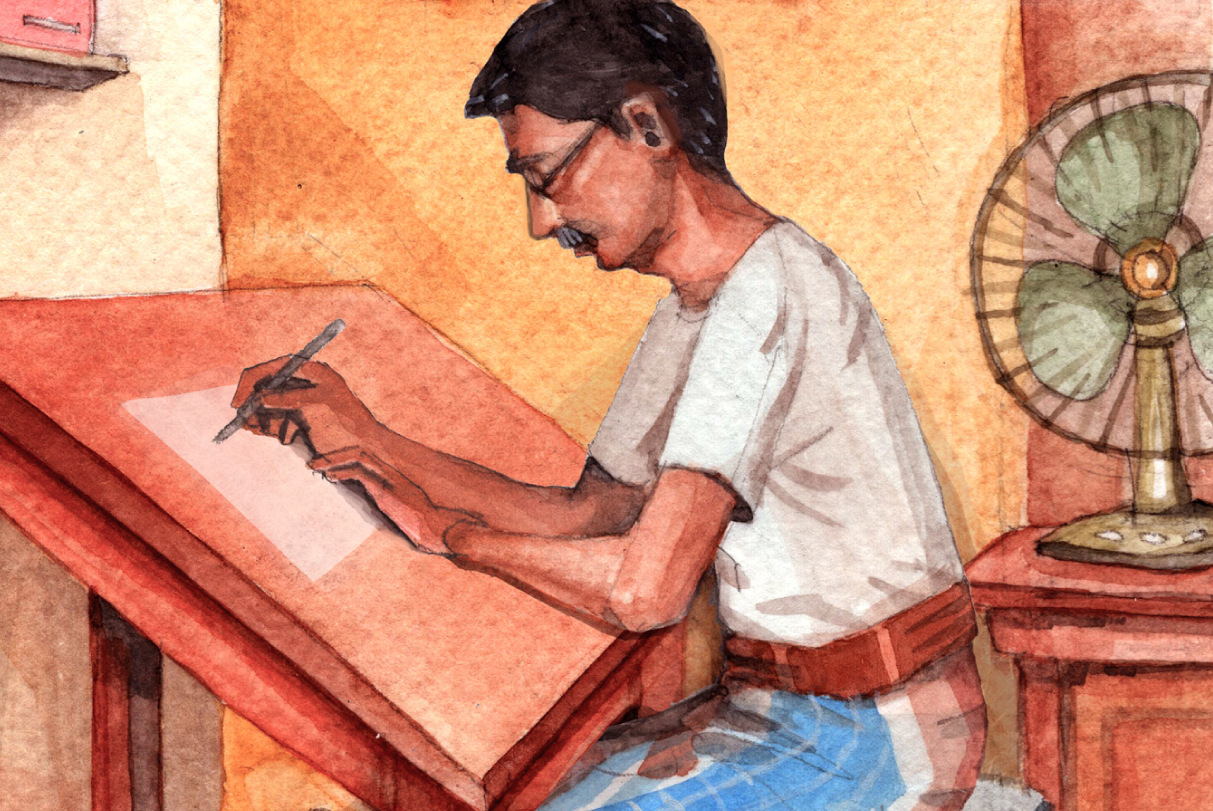

What is your process of making the layouts of the pages like? Do you work with a physical storyboard or is it all on the computer?

I almost never use the computer until the end of the process. Everything is handwritten and hand-drawn and there are several drafts and so many sketchbooks. About the process, I think I should credit my six-year-old son Mir [Ali Banerjee] because I’ve first perfected so many of my narratives in the form of bedtime stories I tell him every night.

Where do you glean points of reference for storytelling from, from a research perspective: via cinema, literature, mythology, or even newspaper clippings perhaps? Who are your influences?

This has definitely changed over the years. In the very beginning, while working on Corridor (2004) it was the gully guy on the streets of Delhi. I would paint for hours every day, observing the guys at Connaught Place —whom we call ‘hustlers’ — so it’s all primary research. With The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers (2007), I had to go through a lot of archival material. For instance, what does a horse carriage in old, Persian advertising prints look like? Or looking at a photo of a Mayan sculpture, I’d get an idea of my character’s facial features. So this kind of research opened up another visual world altogether. The local trains and trams in northern Calcutta, dilapidated buildings, rumours about ghosts in old houses…all of these were influences in some sense. Harappa Files (2011), on the other hand, was made sitting on a sofa and thinking of people I knew. With All Quiet in Vikaspuri (2016), there was environmental research as the story was about a mythical river and a war that is triggered on account of a water crisis. And Doab Dil (2019) is essentially a deep, vast topography of my own reading; the pleasure of immersive reading; books on reading and gardens and nature which I have plunged into. So I work largely within the realm of my imagination now — one does need a sort of open forest to wander, right?

Your work ‘Gallery of Losers’ for the London Summer Olympics in 2012 celebrates those who have ‘almost made it’. What is it about the underdog that excites you?

I think the term ‘underdog’ is problematic. There are so many ways of losing, but just one way of winning. There is a certain dignity, a self-reflective humour with losing. Many years ago, I was at a judo dojo in Brazil during the Sao Paulo Biennale, where I met a judoka named Douglas Vieira, a former Olympic medallist. He defeated a Japanese judoka in the semi-finals but lost to a Korean guy in the finals. When I asked him what losing felt like, he picked me up and dropped me on the mat 12 times. I found this liberating, and it felt good. So in 2012, when the proposal for Gallery of Losers came up, my mind harked back to this incident.

Is there a stage in the process of making a graphic narrative which you absolutely relish or particularly loathe?

When I’m done working on a book, I totally lose interest in it. I don’t find the idea of book launches, or even any accolades, exciting anymore. I’m now in a much quieter space. Maybe age has got something to do with it? I don’t know. But the process itself is extremely joyful — the ideas which first seem totally impossible, and then as you go along, everything slowly comes together and begins to make sense. It’s somewhat like experimenting with cooking, you know.

What is your favourite graphic novel?

I think good graphic novelists don’t do graphic novels anymore. But otherwise I’ve enjoyed Ghost World (1997) and David Boring (2000) by Daniel Clowes, and closer home, the works of Vishwajyoti Ghosh and Appupen.

What are you working on next?

I’ll be visiting Princeton very soon to collaborate with historian Gyan Prakash on a project. I traditionally collaborate with historians because artists either try to become historians and fail or become amateur historians. With Gyan, the idea is to use visual language into history, or discovering how the historical process or the minds of historians work. In terms of the form, it could be an altogether new classroom — part-theatre, part-lecture. Or create a series of illustrated lectures which can be modified into books later.