Growing up in India in the early ’90s, I read a lot of Enid Blyton. I must’ve been about five when I borrowed my first Blyton book from a neighbour in my small town of Nizamabad, Telangana (then in Andhra Pradesh). Blyton’s stories — solving mysteries with the Secret Seven, going on adventures and picnics with the Famous Five, exploring The Enchanted Wood with Joe, Beth and Frannie — have enthralled children across generations. But what I find myself going back to, decades later, is her indisputable gift for food writing.

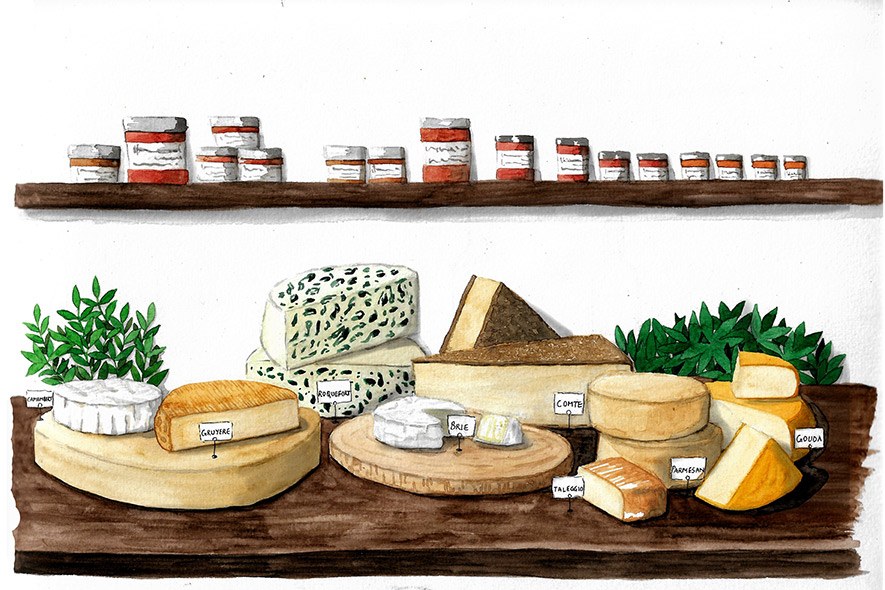

Today, brands would pay top dollar for descriptions so delightful they made an entire subcontinent’s children crave food they had never seen or heard of before. Blancmange (a gelatinous eggless custard), potted meat, tinned sardines, jam tarts, scones, anchovy paste, liquorice… Most of us here had no idea what she was talking about, but we were convinced it was good.

And it wasn’t just the alien pastries. The beauty of Blyton’s writing lay in her descriptions of ordinary food — “a bag of ripe tomatoes and a basket of glossy plums”, “an enormous tureen of new potatoes, all gleaming with melted butter” and “lashings of hard-boiled eggs” were devoured on picnics. There was freshly baked bread and cream to be had at breakfast, and ever so often, “hot, new-made scones, sweet and buttery,” “small ginger buns” and large chocolate sponges with a “thick cream filling” were laid out at tea. Reading these stories, I was sure Nizamabad had received the short end of the stick.

In reality, the food she wrote about was pretty mundane. Enid Blyton was writing during and soon after World War II, at a time when England faced considerable food shortage and rationing. What she described were simple but hearty meals for her young characters and readers. What might have been perceived as an embarrassment of riches was just an enterprising woman deceiving a generation of English children into eating what was in front of them. Her food was a reflection of scarcity, of an island nation making do with the little they could grow and preserve in times of violent uncertainty.

Now the uncertainty is back — this time, all over the world. As the world reels under the effect of a pandemic, many of us have had to rethink our lifestyle. Those of us who have the privilege of staying home, of comfort and of access to food, are adjusting to this crisis by self-rationing and experimenting with what we have. A generation that may have never spent as much time in the kitchen is now stepping in to try out new things and documenting triumphs and mishaps on social media.

Blyton’s descriptions of food make simplicity shine — a lesson that’s key for our kitchens today. Slowing down, we’re finally appreciating what we have and exploring the abundant possibilities that simpler, seasonal foods present. Recipe books are being taken down off dusty shelves, moms are being called for instructions, food bloggers are in overdrive, and experiments in the kitchen abound. With time to kill, I see people diving into the world of home fermentation — making kanji, sodas and kombucha. We’re also baking more — as other sources of entertainment are denied to us, we seek comfort in a warm loaf of bread, fresh out of the oven. Our Instagram feeds are filled with elaborate sourdough experiments and easy banana bread recipes.

Many meals that would otherwise require an outing or, at the very least, a quick online delivery, are now being made from scratch — momos, home-made ice cream and street favourites like pani puri are all being presented proudly. What’s more, we’re quickly learning to make do with what we have in the pantry. Make a banoffee pie using Parle-G biscuits, bake using the pressure cooker if you don’t have an oven, and use local citrus fruits in your desserts when you run out of cocoa.

On a recent shopping expedition, my husband bought two flat slabs of bread. Too dense to be pita or toast, they reminded me of what used to pass for pizza bases at birthday parties in my childhood — slathered simply with ketchup, or tomato puree, with onions, green capsicum and cheese out of a box. Sometimes green chillies were added. It was not something an Italian would recognize. These were days before thin-crust pizza, before Domino’s or Pizza Hut promised speedy deliveries. I made it the same way — for the nostalgia and because those were all the ingredients I had that day. And my husband ate his like a kid at a birthday party, leaving out the crust and picking off the green capsicum.

As our supply chains collapse, we are forced to be more mindful of the way we consume. Our proximity to farms has started to determine our shopping cart. We’re beginning to understand food patterns, seasonality, and the importance of sustainable consumption — ideas that we’ve taken for granted. Even with basics, it’s easy to lay out a feast fit for kings (or at least, the Famous Five). And most importantly, we’re finally learning how to slow down, sit back and enjoy our food in all its simplicity — just like we did with Enid Blyton all those years ago.

Yashasvini Kumar leads the India legal team at an agri-focussed group of companies. She is currently living on a farm with her husband, cat and over a dozen chickens. Find her on Instagram at @yashasvini_kumar.

Rae Zachariah is an illustrator by day and an animator by night. Find more of her work on Instagram at @raezack.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.