One scorching summer evening in Ahmedabad, during the holy month of Ramadan, I make my way to the old city, where my first stop is the office of Munaf Ahmed — a resident of the city and an enthusiast of its Islamic heritage, who leads walks through its historical districts. His passion for the area’s architecture leads us to the Sultan Ahmed Shah Masjid, whose stone pillars, domes and jaalis are almost as old as the city itself. Built in 1414 and named after the founder of the city, the Masjid lies adjacent to the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque, known for its intricate ‘tree of life’ jaali — the unofficial symbol of the city and inspiration for the logo of the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. Beyond, through busy streets where the heady aromas of chai and kebabs greet you, narrower bylanes called khancha open into clusters of homes. These residential precincts are not ordinary sights, but bastions of Ahmedabad’s heritage. They’re called pols, and they hold the city’s storied past.

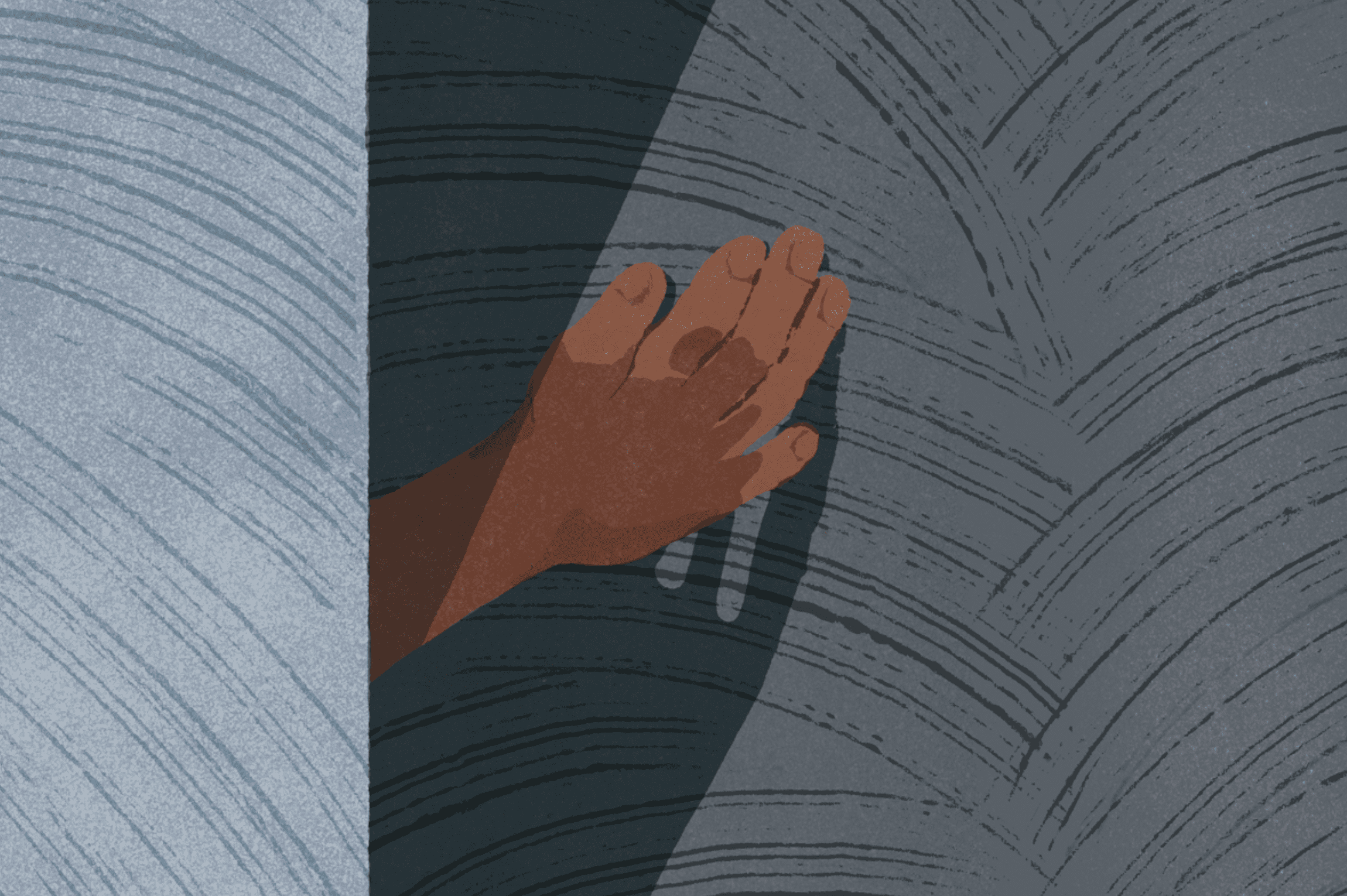

Entering a pol can be a cinematic experience. Everywhere you look is an exquisitely crafted door or window. Pols as a housing typology are believed to be more than 300 years old, and in the old city itself, they emerged in the aftermath of communal riots and civil disorder that erupted in the 18th century. Ahmedabad was a city of merchants, and the locals could afford to design these pols themselves, which would explain the cultural differences evident in the design. This can also be attributed to the various powers that have ruled Ahmedabad over the years — including the Gujarat Sultanate, the Mughals and the British — and their influence on its cityscape. While most traditional houses showcase stone masonry and elaborate wood carvings, there are some with striking Art Deco features, and others that display an eclectic mix of styles. Each pol was once a self-contained settlement where families of the same caste, religion or occupation would settle. The physical boundaries of a pol were often based on the interrelationships among its inhabitants.

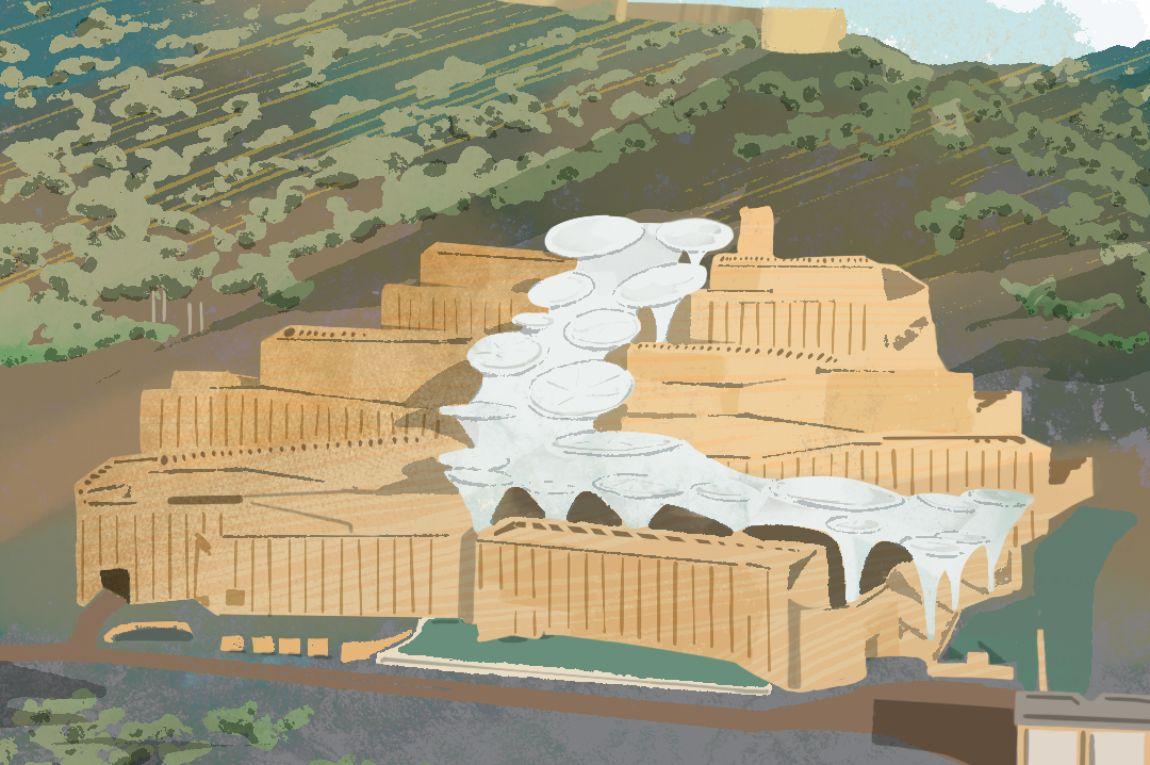

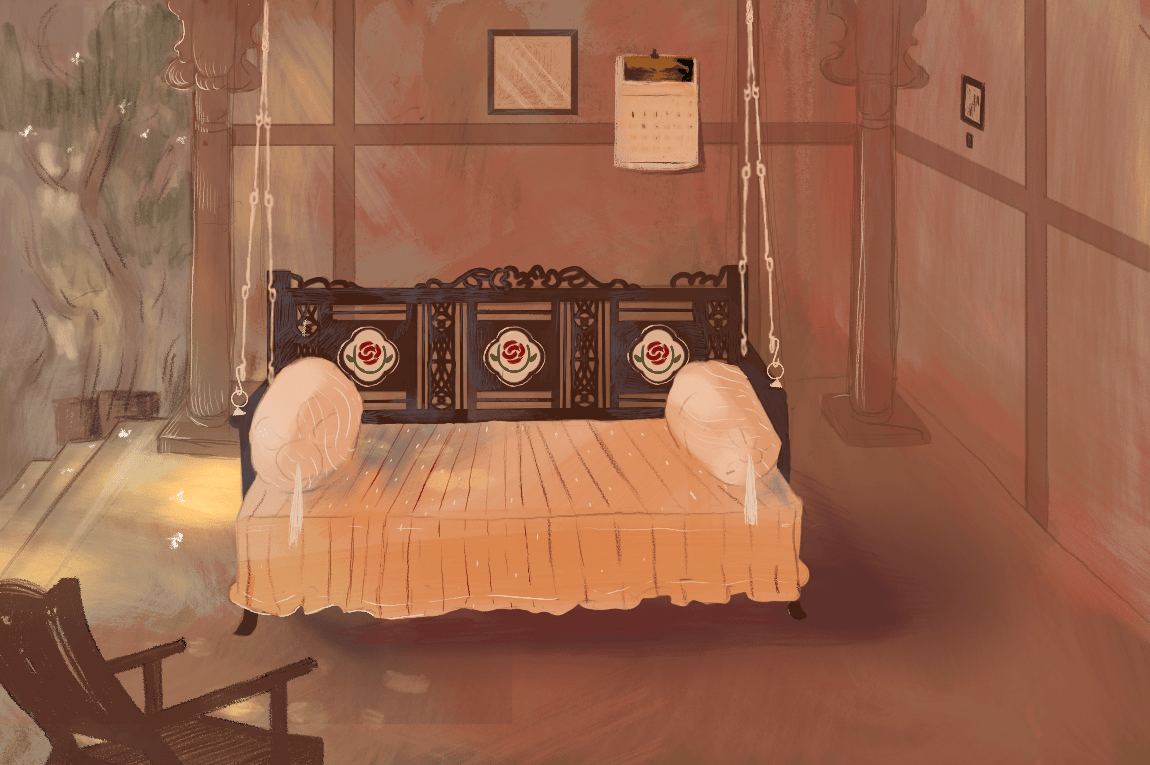

There are roughly 360 pols in Ahmedabad. In most of these clusters, homes with decorated wooden facades — planted with ornate columns and windows, carved bands and balcony railings — some of which date back to the 19th century, are a recurring feature, as are the chabutra (bird feeders), community wells, Jain and Hindu temples, mosques, and public squares. In the more opulent homes, the chhajjas and balconies are decorated with carved brackets and cornices. The otla, the verandah of pol homes, performed the dual function of marking the boundary of the house on the street and serving as a platform for social interaction.

Pols were also built to account for the local climate, socio-cultural demographics and anticipated threats. Within a pol, narrow lanes offer respite from the harsh sun by increasing shade in the khancha and the multi-storeyed homes, while natural light enters homes through the chowks (central courtyards) that also allow cross ventilation. The roofs of pol houses were traditionally sloped, with wooden trusses and Mangalore tiles, which was ideal for the monsoon. The construction — a timber framework with brick walls — insulates the structure against earthquakes. The tankas (underground tanks) — of which there are at least 10,000 within the walled city — were built to collect rainwater to combat water scarcity.

The densely packed layout is known to foster the spirit of community living, but when they first came to be, the pols were classified on the basis of caste, and further fortified because of communal clashes and battles. These influences are still evident in their fortress-like structure — labyrinthine one-way streets that often lead to dead ends, neighbourhood gateways that restrict entry, discreet passages leading to other pols, provisions for storing water and grains in each home. Over the centuries, the pols evolved, as did their function. They became spaces where people preserved their sense of belonging and still managed to coexist.

While the walled city was declared a UNESCO World Heritage City in 2017, many of its Mughal era monuments now lie in various states of decay due to neglect by authorities, as Munaf tells me. There have been some attempts at conservation of heritage structures in the pols, turning them into boutique hotels and B&Bs, but some have also been demolished — or are at risk of being razed to the ground — because they are not listed officially as ‘heritage’. Munaf suggests an attempt at fabricating, even hiding, the reality beneath the oft-romanticised architecture. He’s not wrong, as I learn on an accidental detour through Mandvi ni Pol, where infrastructural issues are a menace noticeable in every khancho.

Although I grew up in Ahmedabad, it was only as an adult that I found a community within the walled city. Since then, I’ve spent many iftar evenings on food walks through pols towards the Jama Masjid, relishing kebabs sold under carved windows of homes, wondering about the lives tucked away behind them.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Saachi D’Souza is a writer and editor based in Goa, examining pop culture and society and all the things that make them. She is on Instagram at @saachdsouza.