Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a monthly column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world. This piece was shortlisted for Condé Nast Traveller India’s Excellence Award for Food Writing 2019.

The simplest way to expand on the paniyarakkal and its cousins across the world is to start with their Nordic ancestor from thirteen centuries ago. The Deccan states make puffy lentil-and-rice-batter balls loaded with onions, chilly, mustard and curry leaves in what looks like a cast iron egg poacher because… once upon a time some petered out Vikings wanted pancakes so badly after pillaging that they couldn’t wait for proper vessels to cook them in. So they popped the batter into their dented shields and helmets, placed over an open flame. These pancakes became puffy balls which eventually evolved into ӕbleskivers.

That’s the theory according to Viking legend and Danish folklore, propagated by Arne Hansen, former owner of Solvang Restaurant in Solvang, California, also known as ‘Mr. Aebleskiver’. Sovlang means ‘sunny field’ in Danish, and is a city that was set up by a group of Danes in 1911, so naturally, Danish food and folklore abound there. Hansen’s home is reported to be a museum to the pastry he’s adored for over 50 years. He has a munk the size of a penny, a large one made of hammered copper, and many scrapbooks about them maintained by Telma, his wife.

The munk or munker, the official but uncommon name for the ӕbleskiver pan, would be easily recognised by many cultures and communities around the world as their own — a piece of very local traditional kitchen equipment, used to prepare foods that have existed in their regions for generations. These cultures would consider these preparations as deeply, historically and authentically their own regional specialties that were invented not far from where they are eaten.

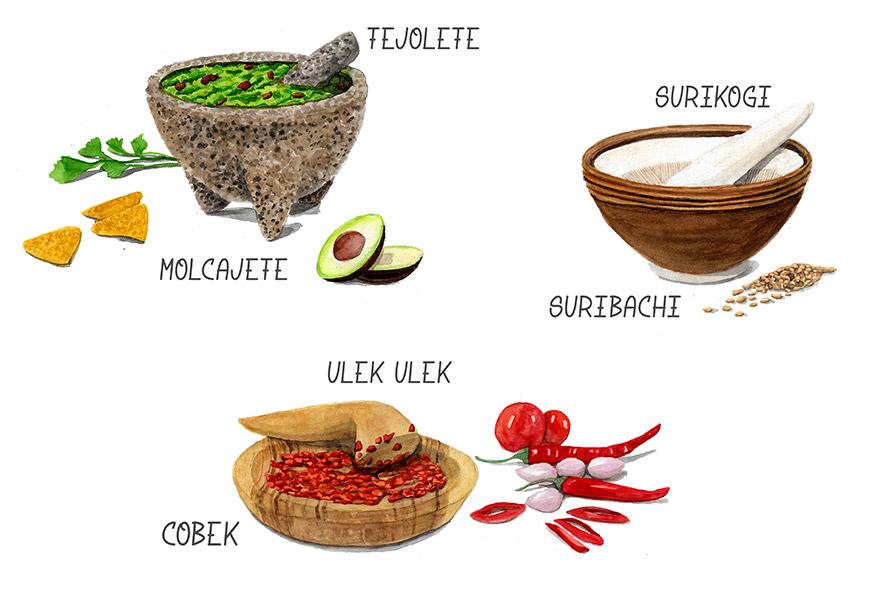

In neighbouring Holland, a munk is called a poffertjespan; in Tamil Nadu, it’s a paniyarakkal; in Japan, a takoyaki-ki; in Indonesia, cetakan kue cubit; in Thailand, gra-ta khanom khrok; in Vietnam, a banh khot pan. Unlike the mortar and pestle which need changes in its materials, forms, and sizes depending on where it is and what’s going in it, or the spork which has changed over time because of inherent design flaws and efficiencies, the centuries-old munk is exactly the same. To us, this is what makes the munker or uniyappam chatti (as it is called in Kerala) a piece of design that is so persistent, it’s travelled across the world unaffected and unchanged.

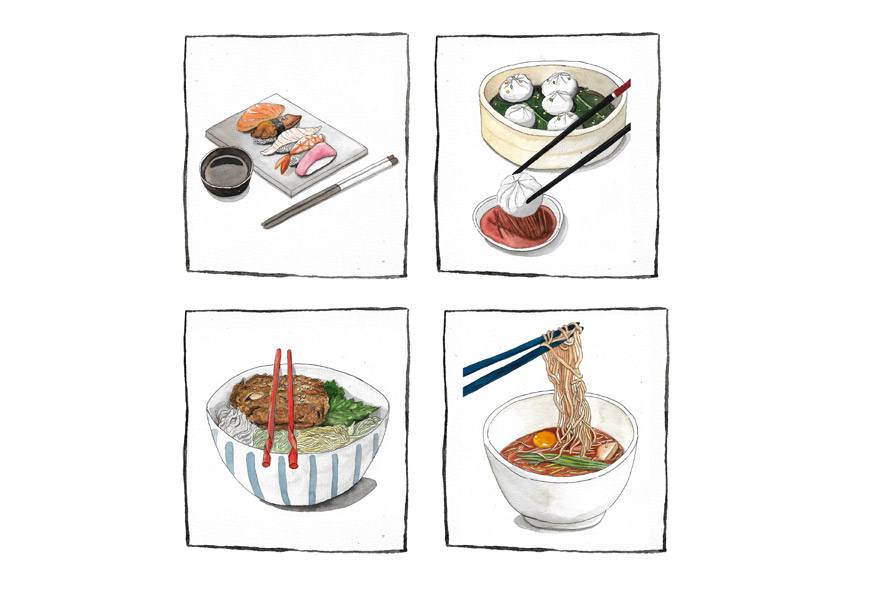

All manner of ingredients, flavours and textures yield to it and become wondrous things that induce feelings of possessiveness and nostalgia in cultures around the world. Its origins are undetermined, its trail around the world is made up of informed guesses at best, and yet, it’s rooted deeply in cuisines that have created foods specifically for it. These are dishes that cannot be made in any other vessel except a skillet moulded to have concave hemispherical indentations. The size of the skillet and its cups may vary slightly — the Japanese may prefer rectangular skillets — but no matter where they’re used, or what they’re called, munkers are almost always filled with some sort of batter. This batter is rotated using knitting needles, skewers or chopsticks to make balls, depending on where they’re being rotated. When cooked correctly, they have a similar structure everywhere: a crusty, crunchy shell outside and cloudy, fluffy, even creamy insides.

If in Denmark these pans were traditionally filled with pancake mix (stuffed with apple slices or applesauce, hence ӕbleskiver), in neighbouring Holland, they were made filled with a buckwheat batter thanks to the French influence. The idea for Tamil Nadu’s paniyarams or Kerala’s unniyappam most likely developed during the 17th-century Dutch settlements in Pulicat and Cochin, using the pan for the traditional local dosa batter, or for a combination of rice, jaggery, ghee and bananas. The Indonesian Archipelago was a Dutch colony for over a hundred years; the kue cubit — which translates to ‘pinch cake’, because it can be picked up with a pinch of the fingers and eaten in a bite or two — recipe is very similar to a pancake recipe. In West Sumatra, rice cakes made with palm sugar and coconut milk are called pinyaram! In Japan, whole tiny octopuses are dropped into the batter. In Vietnam, bahn khot is believed to originate in the Mekong Delta or from the Vung Tao coast, and it contains spiced rice flour, mung beans, and shrimp. They aren’t rotated while they cook, so they have slightly concave tops, and can be topped with fish oil and shrimp powder. There is no limit to the flavours this vessel can contain.

There have been experiments with the material used to make the pans — copper, and in modern times non-stick aluminium pans — but even so, the popularity of cast iron has persisted. As has the versatility of the paniyarakkal or the munker, which continues to grow. We’re still not done, especially in India, with finding new ways to fill it. Paniyarakkal bondas or falafels might become a thing, all thanks to worn-out warring Vikings.

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @roshnibajaj.

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.