Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world.

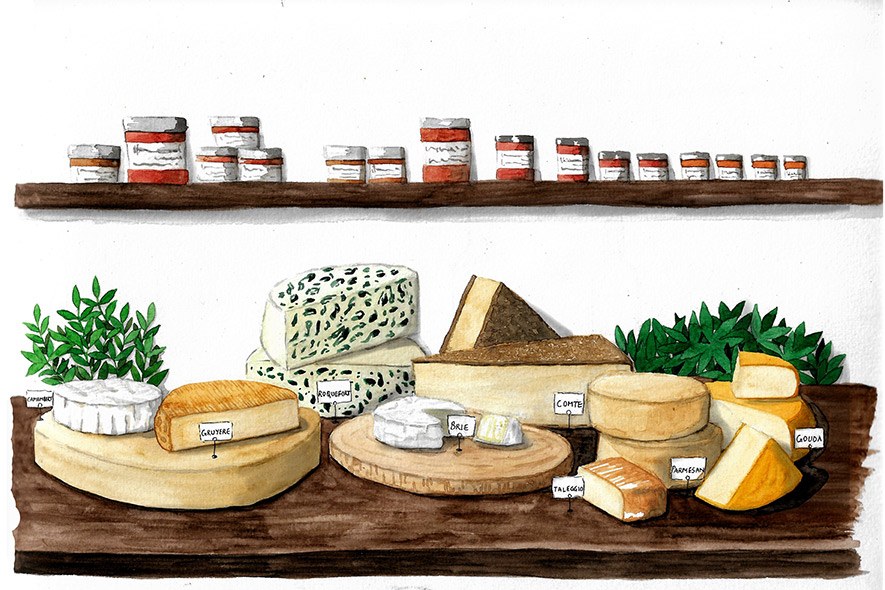

The rolling pin, it’s been everywhere and done everything. The Turkish use the finger-thin oklava for gossamer baklava and börek. The Japanese use a heavy wooden menbo (also more familiarly called rōringupin) to roll out sheets of soba and udon dough before cutting them into springy noodles. The Italians use the mattarello to make pasta and pasticciotti, sometimes freezing heavy steel ones to make sfoglia and frolla. The Swedish use a notched, grooved, and corrugated kavel to make semisweet tunnbröd. Almost all of Latin America uses rodillos to make sweet, sandwiched biscuits known as alfajores. The rouleau is for French fondants and tarts, and that’s not even the start of it.

Many of the dough-based foods we recognise and enjoy today have spent some of their time yielding to a rolling pin.

Some reports claim that the dough dowel was first developed as a cooking tool by the agriculturally advanced Etruscans between the eighth and third centuries BCE. Painted murals by this ancient civilisation from central Italy indicate that Etruscans dressed up for grand banquets, lavish meals and drinking parties, as much for the pleasure of eating and drinking as for entertainment — much like us 21st-century CE humans.

Closer home, almost every Indian kitchen has a wooden belan, always accompanied by a chakla, to make rotis, chapatis, parathas, and more. This version of the rolling pin — with tapered tips — most likely goes back even further, to about 5000 years ago. The Indus Valley civilisation cultivated wheat, millet, and amaranth, and used rolling pins to make wafer breads (which, in fact, sound delicious enough to try in 2020).

There isn’t much to a rolling pin — all it needs to be is an even, symmetrical, cylindrical tool of any size, with or without whittled ends, but with the heft and substance to suit the paste it’s being used to flatten, dough or not. At New York’s recently shuttered Prune, for example, chef Gabrielle Hamilton used a pin for beef carpaccio, firmly rolling tender cuts of meat into thin sheaths, without employing the might of a mallet.

Because their essentials are so uncomplicated, pins can be fashioned from a multitude of materials — with handles (American) or without (French). And they are. Across space and time, they have been made of all kinds of wood, metal, and stone, as well as of acrylic, ceramic, glass and silicone — anything goes as long as it flattens floury pastes well enough. A 1981 story about the advantages and ease of a pasta rolling pin in The New York Times may as well have been written for today. It speaks of a home-made ‘pasta boom’, offering a handy guide for stretching and cutting pasta sheets using merely a rolling pin and a knife.

It’s never been beneath mankind to take a simple thing and add frills to it just for fun. So we also have hand-painted porcelain pins, which sometimes have a cork for a handle so that the hollow inside may be filled with chilled or hot water. Or elaborately carved ones, meant to emboss pastry with all manner of patterns. They can be custom engraved to personalise cookies for every member of the family. There are enough YouTube videos to prove that woodworkers love them, accepting design challenges like this one for a drunken rolling pin.

At the opposite end of the stick, humans have gone barebones, making non-pins into pins. Italians are said to prefer full chilled bottles of wine, their weight and temperature keep the dough cold. After all, fine vino works just as well as fine porcelain — and goes better with pasta.

Because the rolling pin is such a simple tool, even found in nature easily (strip the bark off a smooth cylindrical stick, sandpaper it, use it), it’s hard to pinpoint a creator or a moment in time when the pin came into being. More than inventors, the pin finds improvers. Most famously, Judy W Reed, an African-American woman who developed, and in 1884, patented a pin with a central rod that keeps the handles steady while the body turns. Around the same time, Philip Cromer of Boston came up with a glass pin with a spindle that may be filled with ice for chilled doughs. A more recent rollout solves an age-old problem for amateur chapati cooks: at the International Exhibition of Inventions, New Techniques and Products in Geneva, Switzerland, South African Yvonne Bekker presented a hollow perforated rolling pin that dusts the dough with flour as it works, preventing sticking.

Just as any (cylindrical) household object can become a rolling pin, a rolling pin can be many things. It’s been used as sporting equipment in pin-tossing contests where the target is a life-sized dummy husband. (See also, the rolling pin in popular culture and cliché, best served by once popular comic-strip characters Andy and Flo Capp.

At a stretch, and somewhat less violently, rolling pins can be used to grind spices or crumb toast, and double up as a cocktail muddler or foam roller — depending on what we need most after a long, hot day in the kitchen. On retirement, they can be made into kitchen napkin rods or peg boards.

The rolling pin has indeed been everywhere and done everything. The world’s largest rolling pin? It’s in Wodonga, Australia. Oddly enough, it will only make you roll your eyes.

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @roshnibajaj.

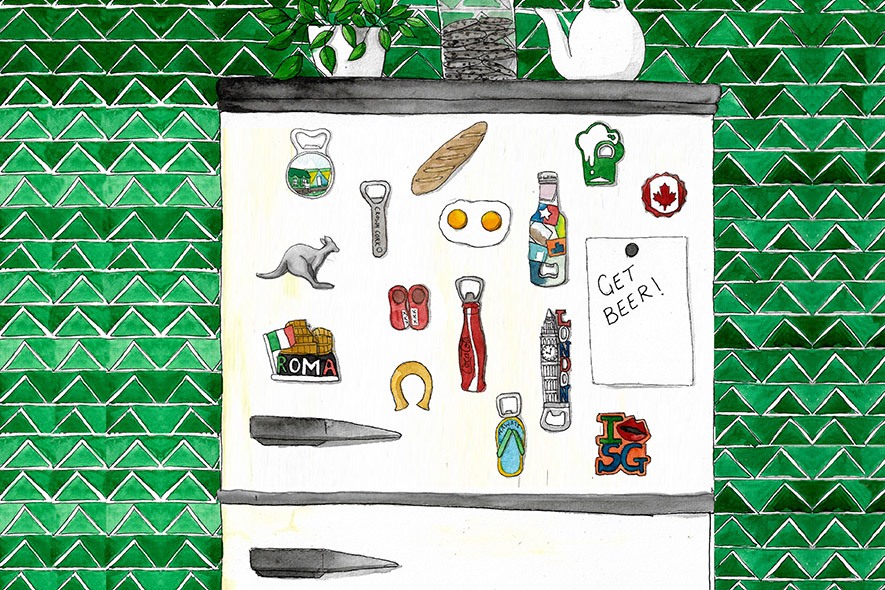

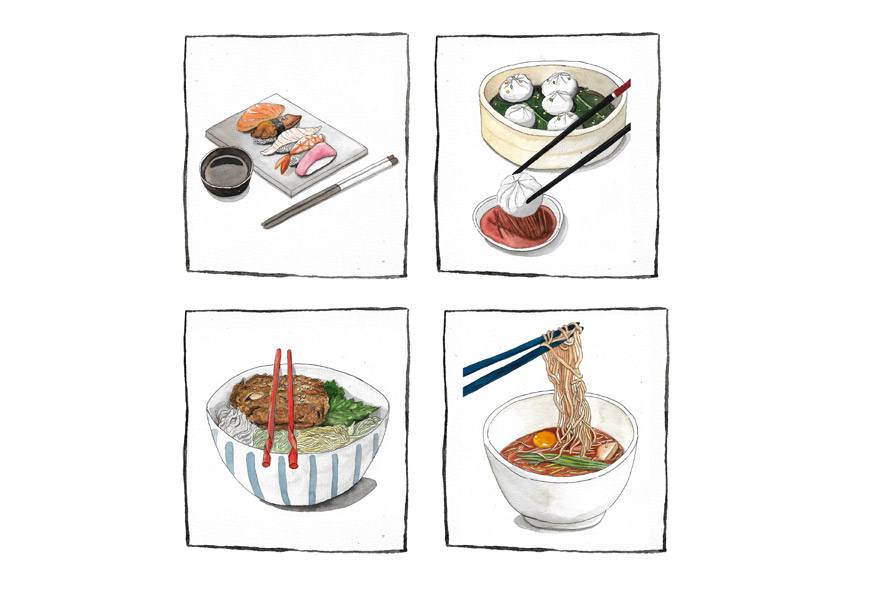

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.