Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world.

We all have that one friend who takes great pride in opening beer-bottle caps with their teeth. And with just this one cool-looking but unhygienic and downright dangerous move, they greatly disregard an ingenious and now ubiquitous, 127-year-old invention, and its prolific inventor who became a millionaire because of it.

William H. Painter was an Irishman who, like many others, looked to America in search for better opportunities, found them, and consequently, changed our beverage drinking habits forever. The mechanical engineer and serial inventor patented 85 inventions in the 68 years he lived; among them, a paper-folding machine, an ejection seat for passenger trains, a machine for crowning blisters, and a shoe blacking box. He’s remembered for none of these, none persisted. But his induction into the American National Inventors Hall of Fame is a study in perseverance. In 1889, he started working on a stopper that would hold gassy liquids in a bottle. He tested one using a flanged crimped metal cap with corrugations that made it look like a crown, or a tiny flared skirt — it’s what we know as the crown cap. His patent was accepted in 1892, changing his fortune and our lives.

Until 1850, most bottles were capped with a cork, or often, in the case of fizzy beer, with a porcelain ball, lined with a rubber gasket, held in place with a wire bail. These were insufficient seals — inefficient, unhygienic, and sometimes, toxic. There was a keen hunt for a better solution. According to this report, 1,500 types of stoppers had already been invented, and the trade papers were saying “it is pretty hard to get up anything in the stopper line which is not already covered.” Painter accepted the challenge saying, “The only way to do a thing is to do it.” And so he did, with the Crown Cork and Seal Company in Baltimore.

Painter’s first crown cap came without a dedicated opener. A perforation on top yielded to a corkscrew which would lift it off — Painter suggested its edges could be teased up with a knife, nail, ice pick, screwdriver (don’t experiment with these at home, they almost always draw blood along with the cap). After some trials with openers that worked as pliers, he started serious work on a dedicated and portable opener for his crown cap. By 1894, he had invented and patented the ‘Capped-Bottle Opener’, which is exactly what we now recognise as the church-key opener, a name that it acquired only in the 1950s, because, er, it resembled an old church key. (Cast-iron replicas of his originals are still being sold, for £420, or about ₹40,000, a piece.)

By the early 1900s, tremendous leaps occurred in industrialisation, manufacturing, transport, business and communication in the USA. This made retail big business, and marked the beginning of consumer culture, which brought with it restaurants and markets, and with them, soda fountains. Demand for fizzy drinks soared, and in 1906, Painter died a wealthy man. Crown Cork and Seal Company had plants in Japan, France, Germany, and Brazil. Shortly after, with the end of Prohibition, beer consumption bubbled up. By the 1930s, Crown manufactured about half the world’s bottle caps. (Fun fact: King C. Gillette was a salesman for Painter, and was inspired to invent the disposable razor after seeing the lucre in manufacturing disposable products.)

While the crown cap persists very close to its original form, the implements used to release the frothy liquid it holds down, have varied vastly and widely in all ways weird and wonderful. With more crown caps across the world came openers in more styles, and like the caps, they also became advertising tools for beverages, prominently Coke and beer. Among the most collectable vintage openers are the ones that were adapted for other functions, such as the industrial-looking church key style used to pierce open flat-top beer cans.

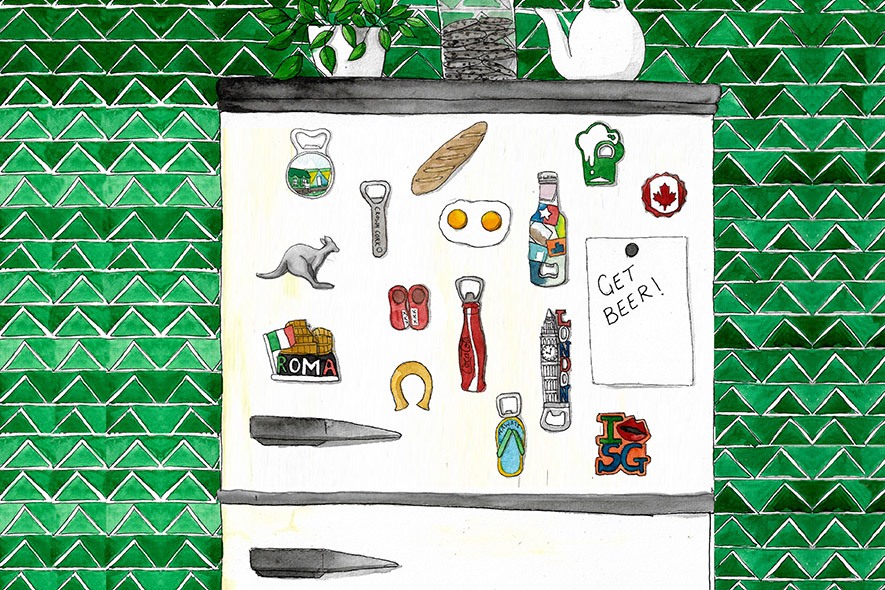

There are probably as many opener styles as there as bubbles in a bottle of beer, so we’ll only dip into the most popular categories here. Around 1925, wall-mounted openers made it easy to pop open a cold one with one hand. These are sensible, especially if there is a catcher below, and more fun if they magnetically suspend the caps on the wall just below them. The tiniest ones are intended for portability and convenience, attaching themselves to keychains. The most basic versions of multitasking tools like the Swiss army knife or the multi-card tool always include one. It’s the decorative ones, which cleverly hide their function, that are by far the most amusing. There’s even a fan club for them. The Figural Bottle Openers Club in Pennsylvania which was founded in 1978, and had its 41st yearly convention last June. It publishes a quarterly newsletter with news about these whimsical openers, including photos and new finds. Further proof that openers induce obsession: a slim volume published 20 years ago promised to be ‘the ultimate guidebook to bottle openers’.

To think opener design geekery is only about collectibles and souvenirs is to be mistaken. In a Wired story, 34-year-old Adam Štěch, co-founder of Czech design firm and creative collective Okolo, says “A bottle opener may just be a bottle opener, but it can actually be a pretty good lens on what’s happening in the design world at any given moment. They reflect new trends in design.” In 2013, Okolo curated 25 openers from around the world to put together an exhibition in Prague. Among the ones featured were Alessi’s little thermoplastic resin dragon called Diabolix, and the bent-steel Italian modernist Splugen opener, designed by Achille and Pier Castiglioni.

127 years later, the Crown Cork and Seal Company not only exists, it thrives. It’s been a Fortune 500 company for 65 years. It’s one of the largest manufacturers of packaging and containers in the world. It has a market cap of $7.6 billion. It still makes crown caps. But it does not make bottle openers any more. It doesn’t need to.

Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @roshnibajaj.

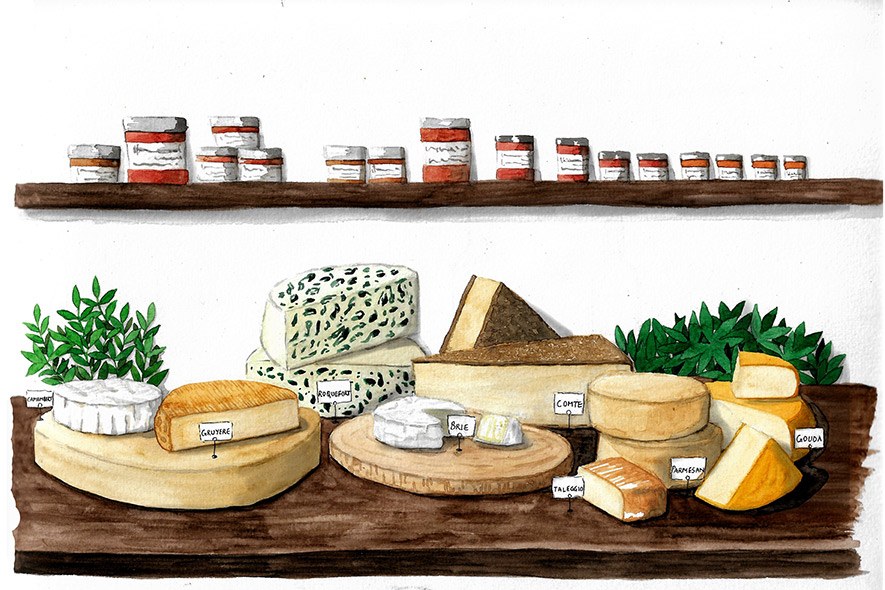

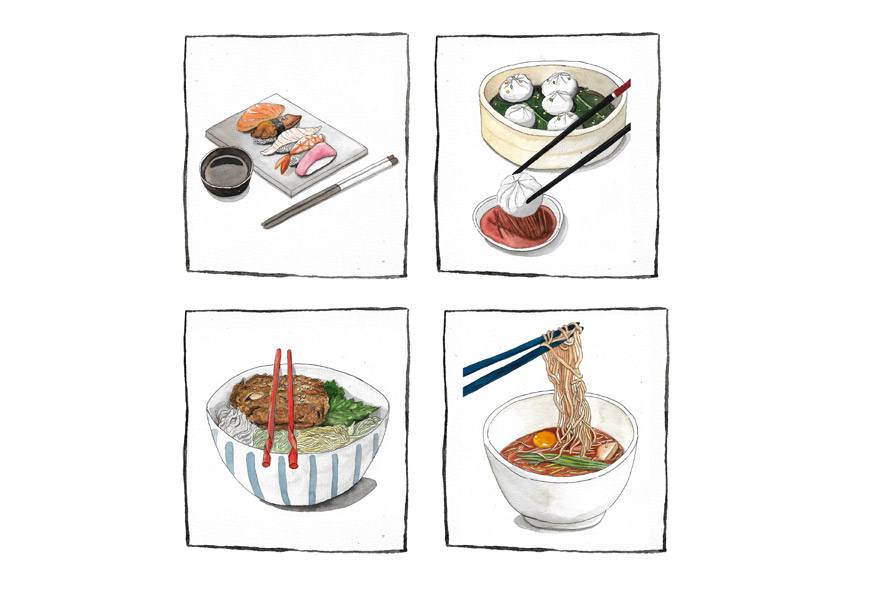

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.