Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a monthly column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world.

Mythology and history remembers the colander best for that time it didn’t do its job. In Ancient Rome, around the eighth century BCE, virgin female priestesses who maintained the fire of Vesta, the goddess of the home and hearth, were called Vestal Virgins. As it turned out, Tuccia, one such appointed virgin, was incorrectly accused of fornication. At the time, the punishment for this deemed sin was to be buried alive with basic provisions. If it wasn’t for a colander and some divine intervention, Tuccia’s fate would have been sealed. The chaste priestess invoked the goddess of the kitchen fireplace, gathered a sieve full of water from the river Tiber and carried it, not to a pot to make pasta, but to the Temple of Vesta without spilling a single drop, thus proving her purity.

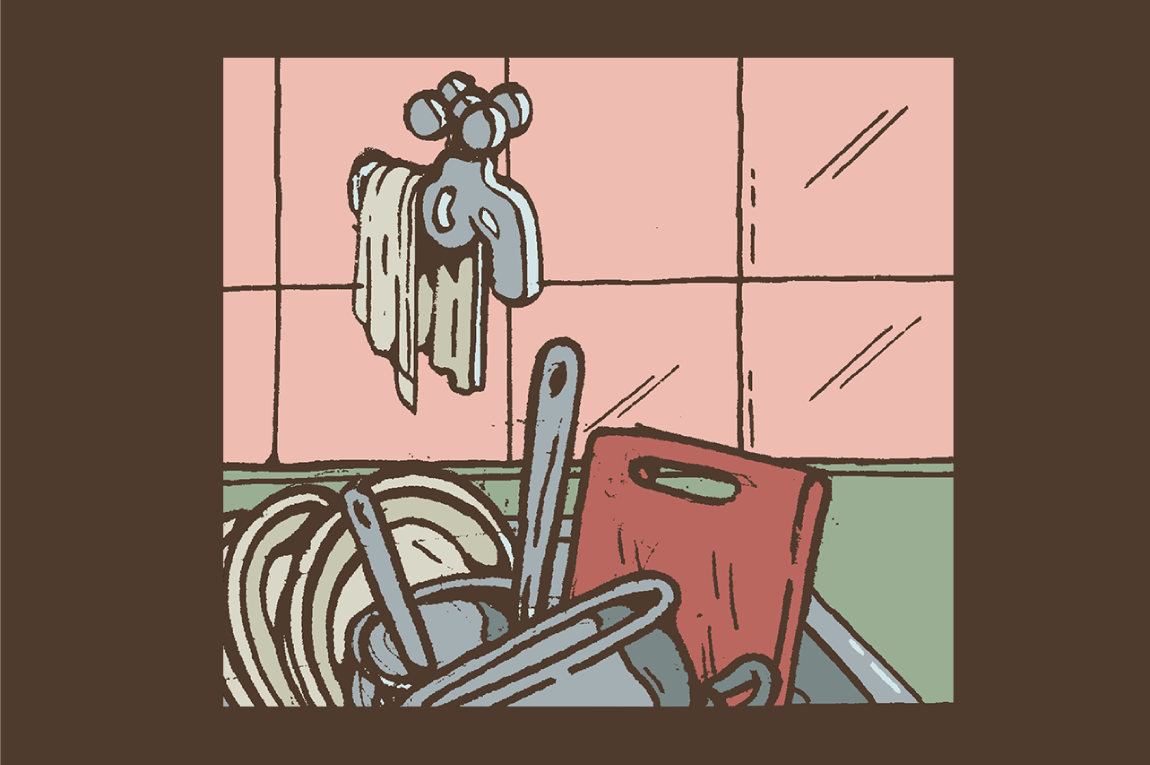

The colander has been an essential implement in our non-mythical kitchens for other reasons — to protect our food and our fingers. It’s really a set of holes held together, typically in a footed bowl-shaped vessel with two handles, made of any material that can be punched and perforated without falling apart. We have — in the history of washing, boiling, simmering and poaching our produce — fashioned colanders from ceramic, steel (both solid and mesh), aluminium, plastic, silicon, wood, bamboo, enamelware, and more. We use them to drain water from produce that’s fresh or dried, cooked or raw. With them, we strain vegetables, leaves, fruits, beans, pasta, grains, noodles… anything really that has solid and liquid components that need to be, and can be, separated. A colander’s mechanics are so simple, it would take a miracle to have it not work. Human beings across the world use these sieves for salads and strawberries, potatoes and parsley, to separate yolks and to strain yogurt, to pan for gold and to MacGyver a steamer. It’s now also a tool for artists who work with acrylic paint, like in this video that’s garnered 6.6 million views.

The name colander comes from the word ‘colum’, which is Latin for strainer or sieve. (Fellow etymology nerds: colum is also the root of the word percolate, with ‘per’ meaning ‘through’, which makes percolate ‘to flow through’.) In the book Pre-Colombian Foodways, the authors state that colanders may have been a Mayan initiative, first used around 1000BCE as a convenient way to rinse corn.

The idea of the colander may well have originated with primitive humans who separated room-temperature solids and liquids using slightly separated fingers. Today, the colander is a darling of designers, covetable to collectors. These perforated bowls have been made from silicone so that they can be telescoped or collapsed until flat. They can be rounded rectangular mesh baskets with expandable handles that suspend over sinks. We have space-saving ones that snap onto the edge of any pot, and are perfect for camping. We have designed them hyper-specifically for berries and for rice.

We just can’t stop tinkering with the colander. Five years ago, London inventor Ran Merkazy created a metal colander that can be squeezed and compacted to a tenth of its size. A year ago, the bestselling Drop colander by Danish design firm Rig-Tig (the name translates to “just right”) sold out in three hours online. Its magic lay in a swivelling semi-circular perforated bowl-shaped lid that enclosed the produce, and a handle that became a hose for tap water. Water poured into and drained from the ball. This is a colander that can (and should) be shaken like a maraca with nary a concern about losing berries or salad leaves to the drain.

Designers have taken the colander and run with it. Philippe Starck (known for his form-over-function citrus press Juicy Salif) designed a relatively more functional sieve for Alessi, and called it Colander Max. It is made of stainless steel that is mirror-polished on the outside, matte on the inside. It has sleek feet, cast in brass, and a constellation of perforations topped with a ring of rabbit-eared smiley faces. (Max was created was in 1987, emojis didn’t exist.) It has a plastic insert so that it can double up as a vase.

Starck said of Max, “One of the ugliest things in the kitchen — or the most ‘nothing’ — is the colander. The object that is hidden under the sink. The object not beautiful with which we spend the salad, spaghetti or whatever. I said to myself: ‘This is really the good example of the object to be ennobled. I made a kind of vase, chalice … Merovingian helmet and I put golden feet.’”

Max currently sells for nearly £300. The statement on Alessi’s website corroborates Starck, “It’s big, beautiful and expensive because of its aesthetics: but its design has a strong impact, which you can’t say for any other colander.” This is an audacious declaration, considering Alessi sells seven other beautiful colanders that are equal marvels of product design. Cases in point: Enzo Mari’s minimalist polypropylene one, intended to provide restraint in our cluttered lives; Dutch designer Marcel Wanders’ from the collection Dressed, intended to showcase its contents without overpowering them; Richard Sapper’s colander from the collection La Cintura di Orione, which translates to the colander of the waist of Orion (the hunter).

Contemporary colander design encompasses both the hypermodern and the nostalgic. Peter Sheldon, a ceramicist based in East LA, inspired by his Vermont heritage, makes one from heavy stoneware with widely punched holes. It may not be the most practical strainer, but it’s certainly beautiful enough to use at a dinner party, or as a fruit- filled centrepiece. More practical, lighter, but equally table-worthy are the hand-painted enamelware colanders by MacKenzie-Childs in Aurora, New York. The twin brothers of English houseware manufacturing firm Joseph Joseph also bring their characteristic unintuitive and slightly irreverent but always clever design twist to sieving tools. The ladle-like Mamma Nessie, imagined by Israeli design firm Ototo as the mom of the mythical Loch Ness monster, is far more commonly recognised than their Spaghetti Monster. (Mamma Nessie is part of a family at Ototo; Papa Nessie is a pasta spoon, Baby Nessie is a tea infuser.)

Nearly thirty centuries after a colander represented religious fidelity, it has become the symbol of young new theology. The Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster is a 15-year-old inclusive rational faith, where “all are welcome into the loving embrace of His Noodly Appendage”. Pastafarians, its faithful followers, question creationism, the existence of god, and the idea that our world was fashioned through supreme ‘intelligent design’ instead of natural selection and evolution. They believe that the universe is as likely to have been created by a monstrous tangle of spaghetti flanked by two meatballs after it had a big boozy night. Pastafarians wear colanders on their heads as religious headgear. This has caused them some trouble in getting driving licence photos.

From ancient Italian civilisations to modern pasta-loving society, this is now indisputable: a good colander can be divine.

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @roshnibajaj.

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.