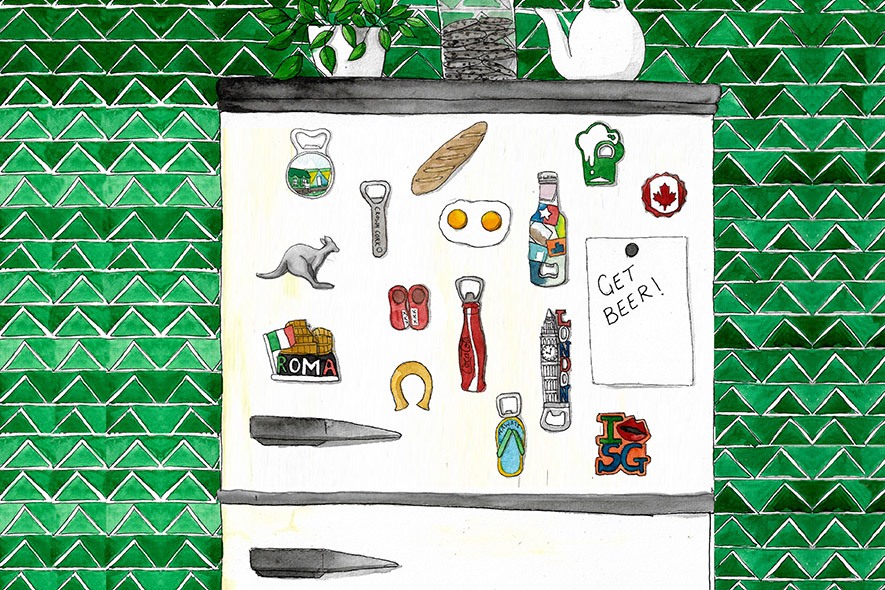

Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world.

Ah, cheese. Made of mainly milk, rennet, salt, and cultures, cheese has been manufactured in thousands of different ways, over ten thousand years. It can be fatty, fluffy, flaky, stretchy, stringy, crumbly, creamy, gooey, grainy, chalky, buttery, brittle, smooth, spreadable, crystalline, cottony, blistered, bubbly, rubbery, rock hard, and everything in between. Cheese has opiate molecules that attach themselves to the same reward centres in our brains that heroin and morphine attach, which makes it highly addictive. It makes our brains release dopamine, it makes us happy. Of course, all we want is more of it, and more ways to eat it.

There are among us, those who would think nothing of breaking off chunks of granular Parmigiano Reggiano with our bare hands, or tearing into a wedge of veiny Valdeon with our teeth, or using a fingertip to transport a blob of baked Brie right from the warm wheel onto our tongues. It’s also perfectly acceptable to use a butter knife, a utility knife, a spatula, a fork, or a cracker, depending on how yielding the paste is, to serve and eat cheese. To be fair, when we come across our first cheese knife set – yes, there is such a thing – we should be startled. Our astonishment should certainly intensify when we encounter this set of three fairly basic-looking knives with handles made of lucite (acrylic resin) and realise they’re not only priced at $425, they’re also popular enough to be sold out on Goop. (The fine print says that each knife is entirely handmade and initialled by a single craftsman, in the Tuscan countryside, using a 125-year-old tradition — all of which might explain the price tag.)

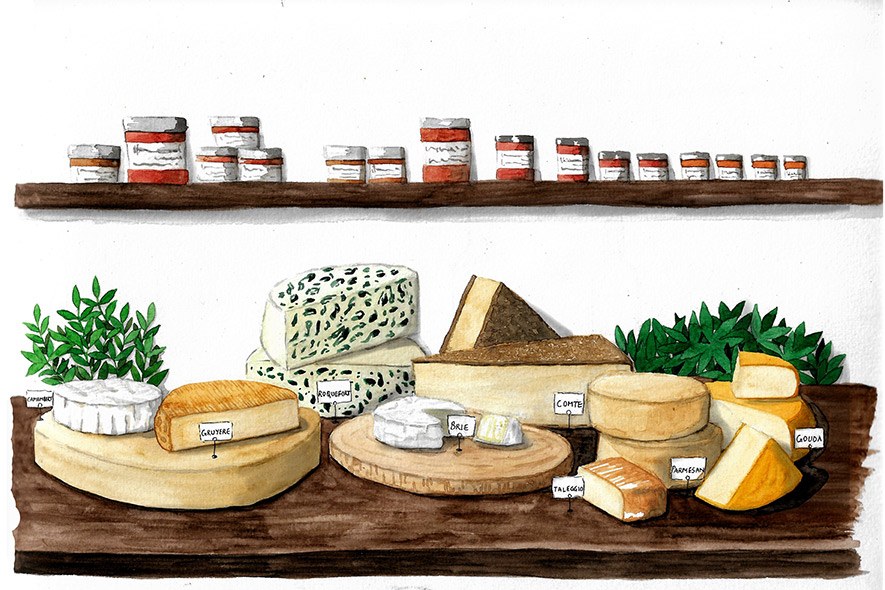

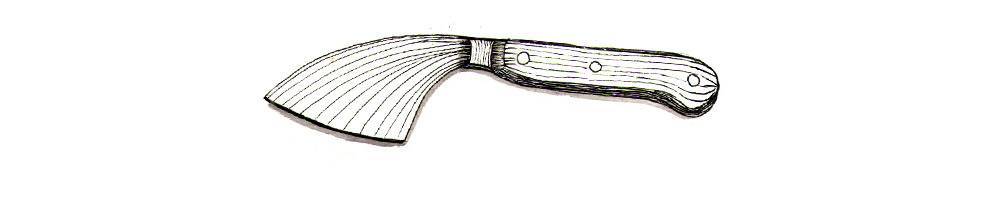

The most rudimentary sets (like the Coltellerie Berti above) have two or three knives to tackle basic degrees of firmness: soft, compact, hard. Further specificity is not hard to find. Even highly rated yet affordable, supermarket-variety knife sets can have up to six pieces, including a spreader or wide-blade knife for creamy cheese (such as ricotta, chèvre), a large serving fork for both buttery and compact cheese varieties (Camembert, Emmental), and a wide chisel knife for hard and crumbly cheese styles (Romano, Gorgonzola Piccante). But devoted cheese-lovers (or curd nerds, as they are sometimes called) would say that these knives barely scratch the surface.

Cheese, with its tremendous diversity of textures and consistencies, tends to inspire product designers, sometimes enough to create tools to beautifully and cleverly cleave and consume very specific types of cheese. There are those designed especially for Comté (two-handled, and also known as Dutch cheese knives), Parmesan (which look like oyster shuckers), and Brie.

Among such ultra-specific cheese cutters, the winner would be the girolle, invented in 1982 by Swiss precision mechanic Nicolas Crevoisier to improve our experience of a cheese first made in the 12th century in Bellelay Abbey. Named after the French word for chanterelle mushrooms, la girolle is used to shave a Swiss cheese called Tête de Moine, French for ‘monk’s head’, into rosettes that look like the frilly fungus. This scraping exposes the paste to more oxygen, which makes the cheese more aromatic and satisfying, and the re-telling of our experience of eating it, more vivid and picturesque. (Before Crevoisier found a way to make floral trumpets of Tête de Moine, it was pared with a regular knife.)

Among cheese cutters, we’re all now familiar with the raclette knife, used to scrape soft blankets of melted cheese onto meat and potatoes. But few of us know about the Stilton spoon. According to A History of the World in Five Dishes by Howard Belton, the writer of Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe, mentioned it first in his 1724 book A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain. At the time, it was employed to eat the (entirely edible, and much appreciated) maggots and mites that lived in this beloved blue cheese. Elsewhere in the world, maggot-ridden Gorgonzola was being eaten with a spoon as well, quite likely with utensils that looked a lot like this antique Victorian silver and mother of pearl specimen, now worth $1,041.

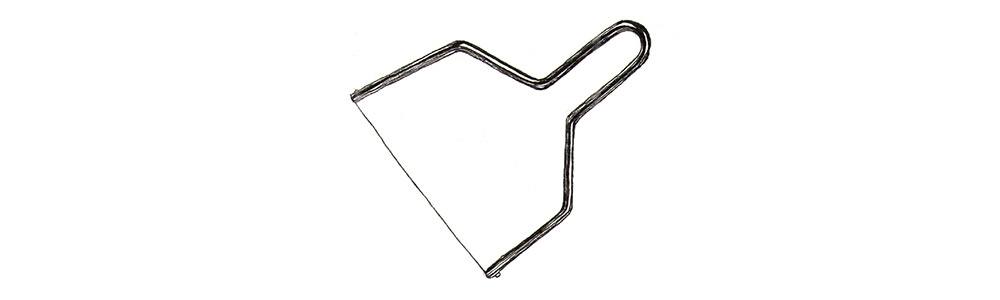

Far more pleasant, now that our blue cheese isn’t infested or motile, is to use a Roquefort bow. The cutter may be named after the elastic arc used to shoot arrows, but this bow’s metal string cuts blue cheese into perfect wedges and slices with nary a crumb or bisected bug astray. Wires also feature in horizontal Brie cutters, are built into cutting boards, and are used just by themselves, especially for large wheels. One way to tell if a cheese shop is serious about its wares? They use cheese wire.

At home, the most ubiquitous way to slice cheese is with a carpenter’s tool – adapted, of course, to suit the task at hand. In 1925, Norwegian woodworker Thor Bjørklund was annoyed. A normal knife did not offer him the evenly thin slices he desired. So he put various tools in his workshop to a block of ost (or cheese in Norwegian), decided that his carpenter’s plane worked best, and went on to patent the ostehøvel – literally cheese-plane. It’s so easy to use, it can make a greenhorn’s Gouda look good.

A century later, we can buy ostehøvels in plastic, find them flipped and bent out of shape at the MoMA, make them in silver and encrust them with diamonds until they get stolen from one of the world’s best known cheese museums. Five years later, the Amsterdam Cheese Museum hasn’t been able to recover their $28,000 Rodrigo Otazu-designed plane, even though they offered the world’s largest fondue set as a reward. It’s probably safe to say, they’re still cheesed off.

Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram at @roshnibajaj.

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.