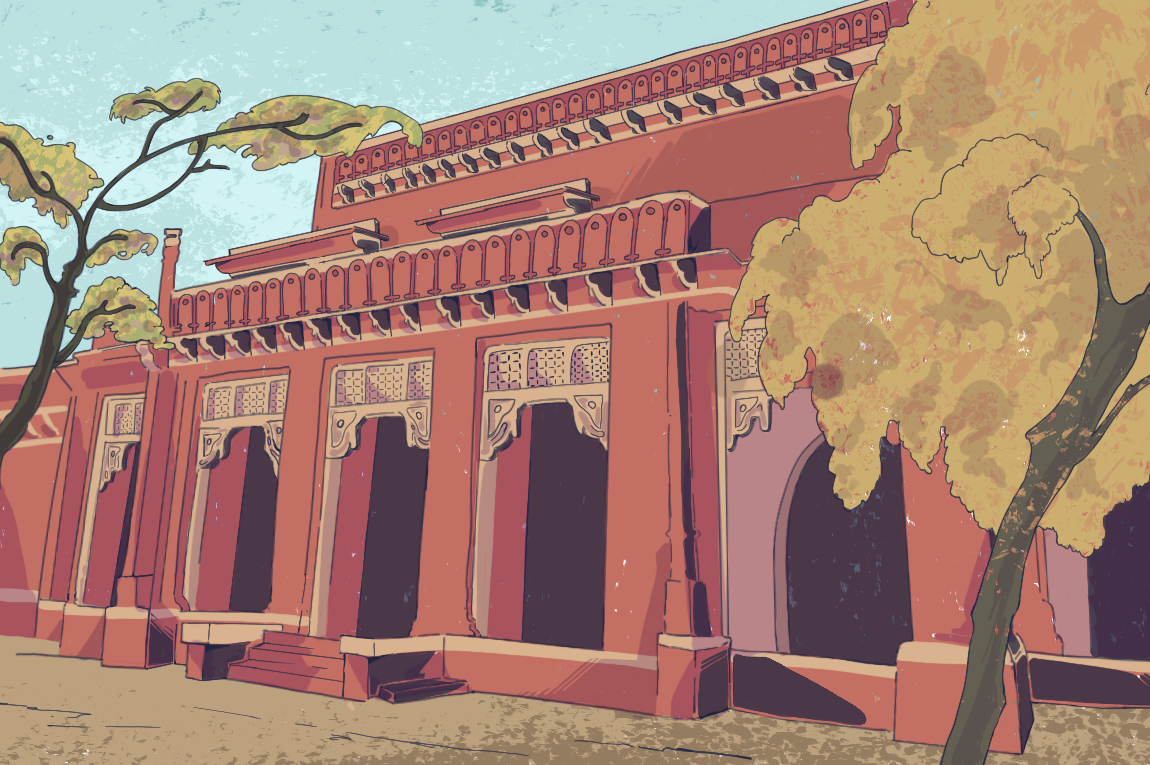

Amidst the pandemic, our family wrestled into a new house in Chennai. It’s a red ochre cuboid, baked by whipping together mud, cement and lime plaster, framed in reclaimed teak wood. In the days following our move, clothes, kitchen utensils and other knick-knacks found room but a stockpile of boxes with hundreds of books still awaited living quarters.

My partner and I had considered scouring the shambolic antique furniture shops that fringed Pondicherry, about four hours away, for a decorative bookshelf. It had always been a favourite furniture haunt for many Chennaites eyeing colonial pieces. These old curiosity shops also abounded with topsy-turvy stacks of scavenged wooden beams. The giant Jenga blocks of teak, rosewood and other local hardwoods were debris from vintage homes. We happened to learn from our architect that many of them were being lapped up by a coterie of new-age furniture makers — Vincent Roy being one of them.

We visited Roy’s workshops and home close to Pondicherry to meet the twinkly-eyed Frenchman, and as we spoke, quickly realised that he was an apt choice for our book-stacking needs. His craftsmanship was a stark contrast to the rococo-style, antique pieces we normally bought. It mimicked the style of mid-century Scandinavian designers like Ib Kofod-Larsen who focused on functional woodwork with clean lines and rounded edges. “Often it is related to things we don’t see,” said Roy. “About custom-making cushions or improving the flexibility of a seat.”

After ping-ponging a few weeks on drawings, we decided on a bewitching yet practical book rack that would double as a nifty study space. Roy designed a 11ft by 5ft bookshelf of Burma teak reclaimed from old British and Chettiar homes. Sliding rattan doors, made with Andaman cane, ornamented four of its five shelves. The lowest rack became a foldable study table. A narrow, removable storage block wedged below this workspace came with three drawers, each with brass knobs from his travels to Java, Indonesia, over a decade ago.

A couple of months later, the nuts, bolts, planks and shutters of the bookshelf vroomed through our bamboo gates on a mini truck. Roy had another cabinet maker in Chennai piece it together for us. “I like to think of my competitors as part of a cooperative. We share information about materials and work,” explained Roy. These partnerships proved invaluable during the gridlock of the pandemic.

He imbibed this collaborative philosophy as a farmer boy growing up amidst juicy grape vines in Cognac with his family that has made the signature brandy for five generations. Vineyards often supported one another as part of agricultural co-ops in this region.

In his two cacophonous workshops, wedged on either side of a narrow alley, more than two dozen workers chisel, sandpaper, polish and bolt together furniture. As these spaces burst through their seams, Roy, previously drained by the clampdowns of the pandemic, finally feels optimistic to embark on building a larger workshop set amidst lush coconut and cashew groves near Auroville. Still, he is resisting the urge to become any bigger. “I don’t want to become a faceless factory,” explained Roy. “I want to maintain a humane scale where I can hand-hold craftsmen to make pieces that have character.”

At home in the quiet cul-de-sac, neem tree–lined street that we have finally settled into with our two homeschoolers, the bookshelf and its playful rattan shutters occupy centre stage as a reading, writing, research and debate hotspot. Long-outgrown children’s books huddle on the neck-craning top shelf and the now-popular coming-of-age comic books throng its lower rack, just below bird books of my nature-loving partner and my favourite graphic novels. This space will have many stories to tell.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Anupama Chandrasekaran is a former business journalist who now produces audio documentaries and writes on development-related issues. She also spins an independent podcast on fossils and prehistory. She is on Instagram as @indiantimbre.

Madhav Nair was formerly part of the editorial team at Paper Planes. Most of his work as an illustrator and graphic artist is published under the pseudonym @deadtheduck.