This is an excerpt from Soul of the Nilgiris, a rich collection of stories and photographs that serves as an ode to the Blue Mountains situated in the Western Ghat region of southern India.

In the high Nilgiris landscape of the Toda community, myths bear like a life force in the forests and hills. The sacred buffaloes roam freely, their bells tinkling in the wind. On windy days, in the steep hillsides, a low hum rings in the ears like a chorus of chants. Staring long and hard through the mist, I would expect the source of the sound to appear from the depth of the Shola forests. My unapologetic love for fantasy notwithstanding, I think I may have spied on faint glimmers of something through the woodsy darkness. There is a particular magic to starlit skies when experienced from the vast, open wilds. Pasts permeate the musty air of old houses so heavily that whispers escape through the cracked walls. It could simply be the elements at play, but in the mind of the indigenous people of the Nilgiris, and very soon to me too, it was always more than the obvious.

Indigenous commons are living entities made up of veins and blood, rhythms and geometries, histories and stories, the mythical and the mystical. Together, they reveal more than a physical landscape: the air vibrates with ancient lore, seasonal cycles reverberate with prayers to ancestors and the legends of bygones. From this symbiosis emerge patterns that are infinitely more than the sum of their parts.

It is the mystical in the place that I am drawn to most: to me, it is legends and folklore trying to make sense of the physical landscapes, shaping the human experience, and in turn shaping how this human experience affects the land and its wellbeing.

The Kurumbas believe that the spirits of their ancestors dwell near the peripheries of the deep forest hamlets, often near old trees and rocks. The ancestress goddess of the Badagas, Hethe, was a wise woman who lived in the mountains. The Todas too believe that their gods once lived amongst them, before breaking away to reside on the Nilgiri mountain peaks, protecting, nourishing and sustaining the lands.

To a city dweller, these might seem at best, warm fantasies woven on cold nights, or at worst, silly superstitions. But what such a perspective might not account for, is the role of human imagination in everything we have today, from real currency or the disembodied idea of rationality, to the idea of man as the supreme being on earth. In the world of adivasis like Kurumbas, Badagas, and especially the Todas, the forest and its parts are not different from their own sons and mothers. They live among the trees and rivers with the recognition that their own life and soul is inextricably entwined with the life and soul of the Nilgiris.

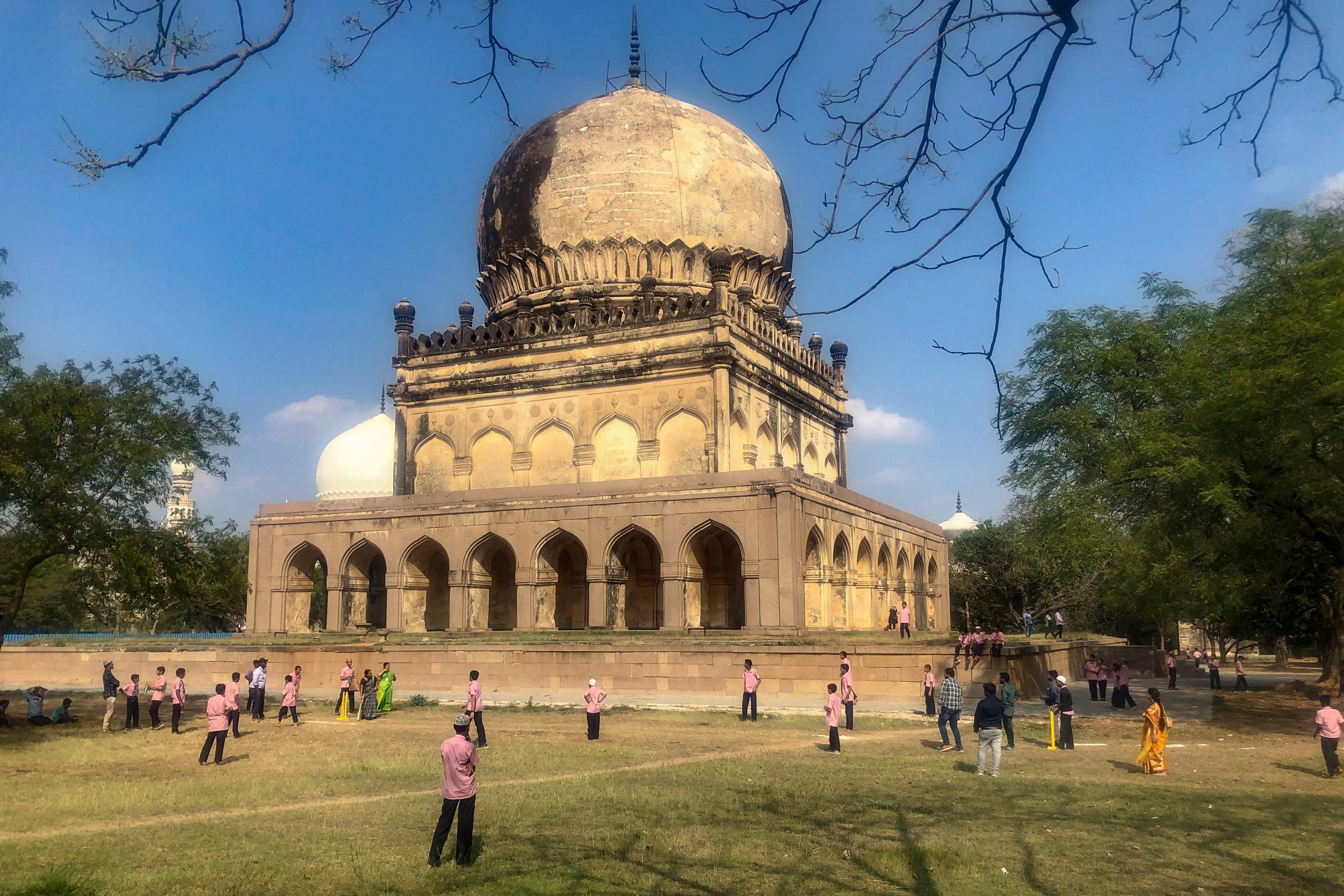

A Kurumba shrine.

Kaavyasin, from Bikapathy mund.

The Todas are the most ancient, indigenous, pastoral people inhabiting the Nilgiri hills. They live on the highest reaches of the Nilgiris plateau, in hamlets called munds, made of unique barrel-vaulted homes and dairy temples, and typically set in the montane grasslands with adjoining Shola forests.

One of the oldest communities in southern India, the Todas have attracted anthropologists from across the world for a couple of centuries. English anthropologist W.H.R. Rivers, who researched the Todas between 1901–02, says in his monumental book The Todas (1906) that he was reproached by more than one contemporary academic for going to “people about whom we already know so much.” Rivers, however, believed there was a lacuna in certain areas and proceeded with his research.

My essays on the Todas are about the wisdom behind some of their practices and why they might be relevant in the times we live in; how their folklore annotates the nuances of the land; and finally my conversations with the elders who hold some of the last vestiges of undiluted Toda culture.

Much of Toda life was (and is) centred around the dictums of their supreme deity, the goddess Taihkirshi. The Todas believe that Taihkirshi and her father Aihnn, are the supreme father-daughter duo who once ruled their pastoral community. This manifestation of the supreme male-female duality as father-daughter is similar to civilisational theologies that emerged much later in the world, where the masculine was attributed to the innate but dormant all-encompassing spirit, and the feminine as all creation that harnesses this spirit.

On her father’s instructions, Taihkirshi domesticated the buffaloes and devised the sacred dairy system, which is at the heart of all Toda life. The sanctity of the majestic Toda buffalo, a rare breed of wide-horned Asiatic water buffaloes (now facing threat of extinction) is woven into everything from their shawls to their eating habits: the Todas are vegetarian. In fact, they are one of the few vegetarian aboriginal groups in the world.

The dairy is not just an occupation, but keeping and tending to buffaloes are deeply spiritual activities bound with life’s rites of passage. It transcends the mundane concerns of ownership and economics. Only a Toda ordained in elaborate ceremonies can qualify as a priest. Only this man can milk the herd belonging to that temple grade, and process the milk into butter, buttermilk, curd, and ghee.

The Toda pastoral duties include rituals intended for the well-being of the ecosystem. For example, the dairy priest gives salt water to the buffaloes in a ceremony at the onset of different seasons. The water drawn for this ritual is from a protected stream or pond of high sanctity. The salt ceremony marks the tribe’s hope for — some would say hand in — the rightful transition of seasons for the health of the ecosystem, ensuring that the buffaloes continue to bless the community. This is an indirect method of conservation in itself. Just a week after prayers are offered at the end of summer, the Southwest monsoon reaches the Nilgiris.

The Todas have mountain-dwelling deities for every peak across the Nilgiris. The mountains are living ancestors protecting and guiding people on the path to the Amunodr, or the other world. There are 14 landmarks that trace the route to the afterworld in the remote southwestern Nilgiris. And we know from Tarun Chhabra’s journey (in his book The Toda Landscape) with his Toda elder friend that these landmarks actually do exist.

Among deity hills are rocks, cliffs, streams and structures that are not dwellings, but are gods in themselves. Each has a dedicated sacred name known as kwarzshm. Sanctified through myth and ritual, these places remained protected. For instance, the sanctity of a stream meant that water be respectfully drawn from it; the spring or pond near a temple was strictly used for temple duties while another near the hamlet provided water for sustenance.

The Shola forest, the wellspring of the Toda life, takes thousands of years to fully manifest and the Todas were actually aware of this. They have a strong sense of how much they can take from the mountains and forests. Ecological understanding and methods of conservation are passed down through generations via folklore.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.