In May, a host of Sterling Prize-winning architecture practices announced Architects Declare, a landmark call to action for biodiversity loss and the current climate emergency. Launched in the UK, the movement has gained momentum globally with more than 600 firms pledging a ‘paradigm shift’ in the way we build.

Although symbolic, this declaration is an important one. Buildings and construction account for nearly 40 per cent of energy-related carbon emissions. According to estimates, the next four decades will witness the built environment expand by 230 billion sqm, globally. That’s a growth rate of approximately a Paris-sized development per week. In India, the building floor area is projected to supersede that of North America and Western Europe by 2050.

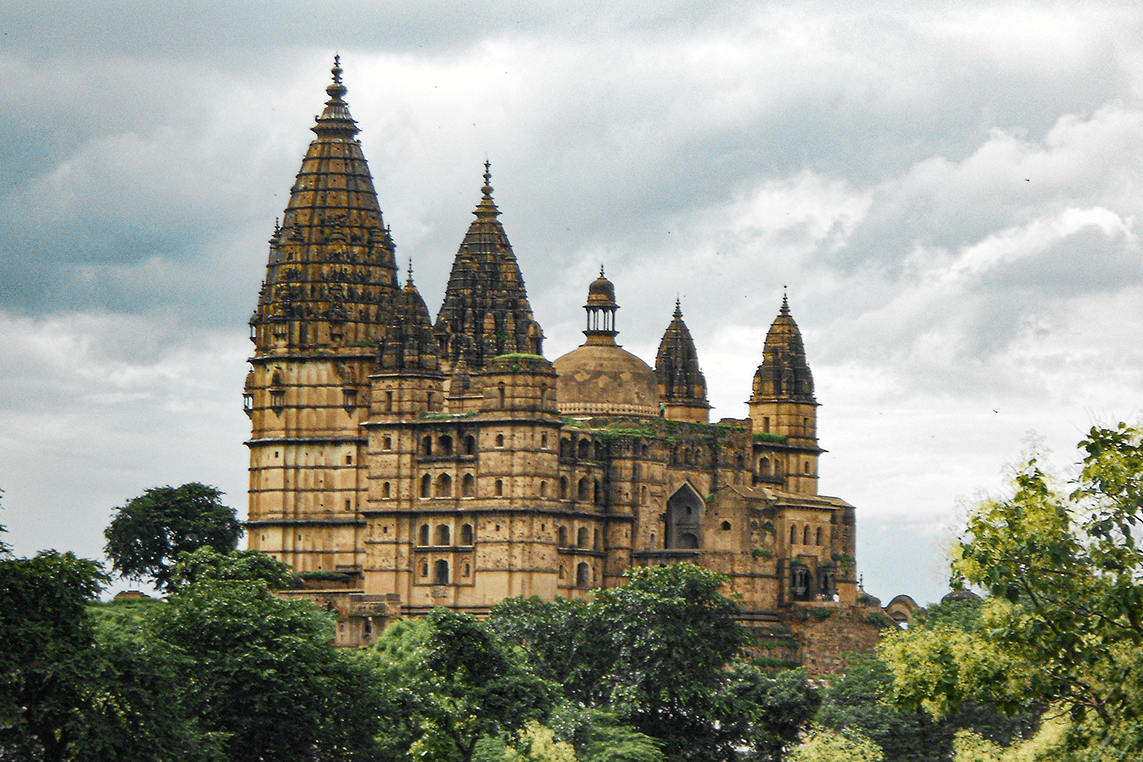

As the world fast approaches an ecological tipping point and the design fraternity navigates a reformed vision of urban practice, we are reminded of the ideologies of the late Charles Correa. Dating back to the Fifties, his body of work spans close to five decades with projects ranging from low-income housing and luxury condos to commercial centres and cultural institutions. The multi-award-winning architect’s modernist sensibilities may have been influenced by Le Corbusier, but were defined by his culturally sensitive building approach.

In many ways, Correa brought India’s vernacular architecture, with its inherent principles of sustainability, into the mainstream building practices of post-independence India. Along with his contemporaries, he pursued a situated architecture where comfort and wellbeing were achieved via passive design elements, like courtyards and pergolas, that capitalised on natural light and ventilation. Similarly, it involved using less-processed, local materials. “This approach when developed rationally and rigorously can lead to mitigation and even perhaps adaptation [to the current climate crisis],” says Himanshu Burte, an architectural theorist, urbanist and associate professor at the Centre for Urban Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay.

In a 1983 Thomas Cubitt lecture, Correa said, “We are only as big as the questions we ask.” The big question today is one that “includes issues of justice inherent to its [sustainability] practice that architecture needs to take seriously. The deteriorating social fabric and the rise of privatised consumer culture is something that design needs to address urgently,” says Burte.

It was Correa’s critical attitude that made a design modern; not a particular school of thought (such as European modernism). It is this very quality that architect, urban designer and filmmaker Rohan Shivkumar finds lacking in recent times. He observes that ideas around sustainable design are more representative of Western trends, than responses to our cities’ particular needs.

Shivkumar’s recent documentary Lovely Villa is named after his childhood apartment block that’s part of the Correa-designed LIC Colony in Borivali, Mumbai. The residential society is replete with terraced buildings and open-to-sky community spaces that encourage a close relationship with nature and neighbours alike. “A particular imagination of a better life was encapsulated in the design of the colony. Growing up there, one can’t help but be influenced by what those spaces represented,” he says.

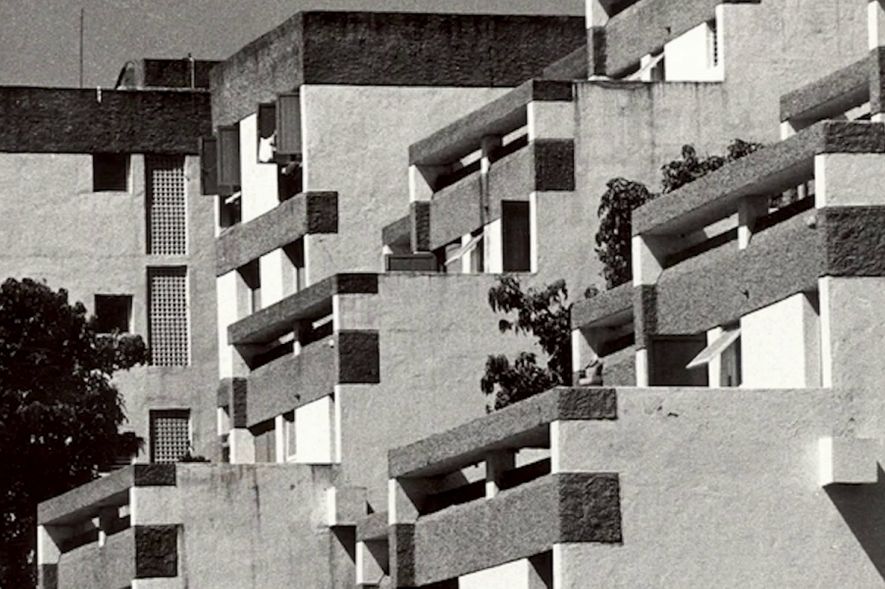

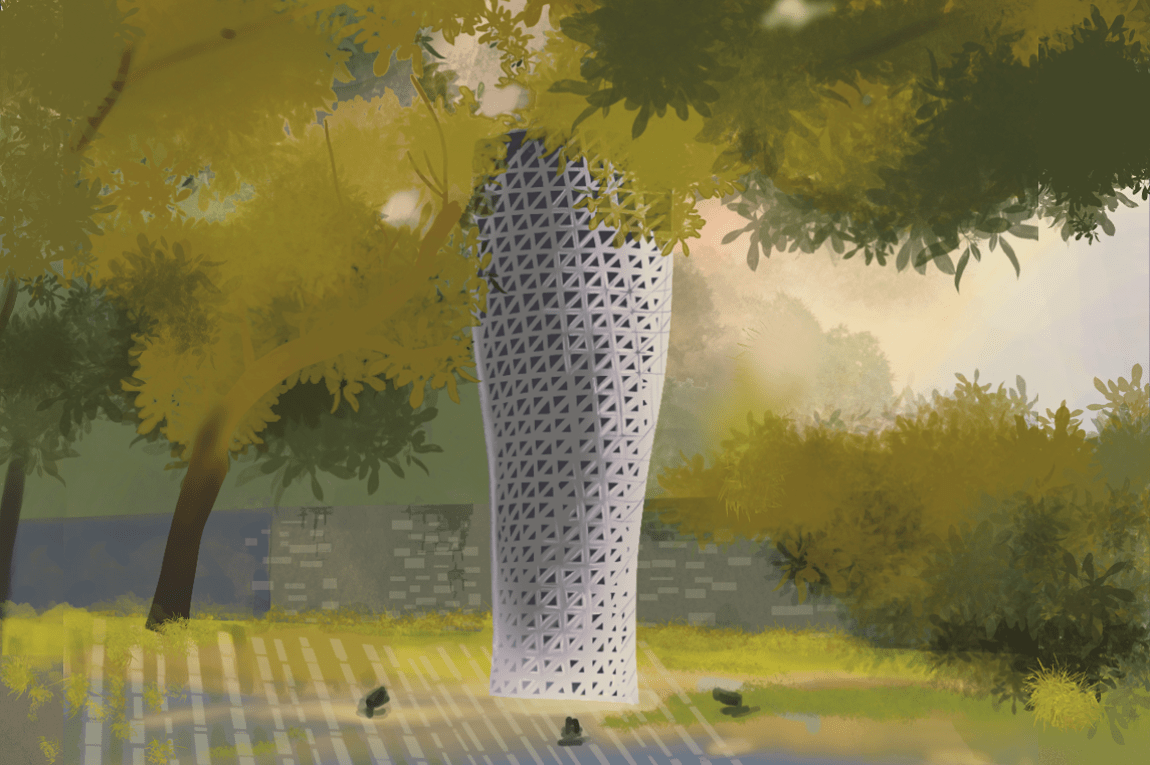

Shivkumar draws on Correa’s astute ability to question the conceptual core of a project. For example, the 32-storey Kanchanjunga Apartments, in Mumbai’s tony Cumbala Hill, demonstrates inventive cellular planning, with its cantilevered terraces that are open to as well as protected from the elements. Then there is his 60,000 sqm Incremental Housing project at Belapur, Navi Mumbai, which illustrates how open spaces are possible even with high densities. The simple layouts allow the houses to grow with their residents’ changing needs and aspirations.

As an urban planner, Correa foresaw the problems of rapid development that our cities grapple with today. He envisioned Navi Mumbai, for instance, as the world’s biggest city that would help decongest Mumbai. The architect condemned political and market forces for its partial failure.

But Correa’s brand of eco-socialism may have lost relevance within the Nineties’ capitalist framework, points out Kapil Gupta, co-founder of international practice Serie Architects. Unsurprisingly, it’s these resultant consumption patterns that have fuelled our current ecological emergency.

Gupta reminds that Correa’s regionalism was primarily driven by identity politics, but agrees that it was also about sustainability. “The role of regionalism should increasingly be a material one,” he explains. Architecture’s focus should be directed towards consuming less – via adaptive reuse, intelligent passive design, and technological innovation like eco-smart materials.

Gupta, whose firm is reputed for cutting-edge, contextually engaged designs, says that sustainable design is currently a USP for many businesses. But he believes it will soon be the norm that also defines policy.

In his essay Learning from Marine Drive, Correa established that almost all development involves a certain exploitation of resources, just as conservation implies the reverse. He advised finding “that point of trade-off where both objectives are optimised.”

Gazing out of the kind of linear, mechanically engineered bubble that Correa cautioned against some three decades ago, we see homogenous skylines, trite in their world-class appeal, and wonder if perhaps, we’ve tipped the scales too far already? Are movements like Architects Declare realistic in a market-led culture? The answer lies in the value systems of a society and the ability of its architects to illustrate the power of good design, while renewing their role as agents of change and social equity.

Gretchen Ferrao Walker is an editorial consultant who has collaborated with Indian and international publications like GQ India, Forbes India, Time Out, Architectural Digest India, Design Anthology and Collectively.org. She is the former editor of travel bimonthly Time Out Explorer and current mum to a 2-year-old. She enjoys embroidering and making pictures.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.