In Srinagar, the graveyards could easily be mistaken for gardens. On the graves of women bloom roses and Ashk-e-Maryam, a kind of lily. And on the graves of men, vibrant irises and daffodils. Devika Krishnan, a Bangalore-based designer and design consultant with Commitment to Kashmir, recalls confusing a graveyard for a garden, albeit with “a very strange layout,” up until the master craftsman Hakim saab she was working with pointed it out. “Yahan pe tho log marte rehte hain, aapko patha hain na, hamara haal kya hain. People die all the time here, you know the state of things,” she remembers him saying. “But why should we leave qabristans (cemeteries) like qabristans — yeh toh hamare Mughal gardens ho gaye na? These are our very own Mughal gardens, right?” Each family has a day for the dead, Krishnan explains, where the family gathers at the graves to tend to the flowers as well as neighbouring graves, and to pray, chat and laugh together. “It’s just such a beautiful community spirit,” she says.

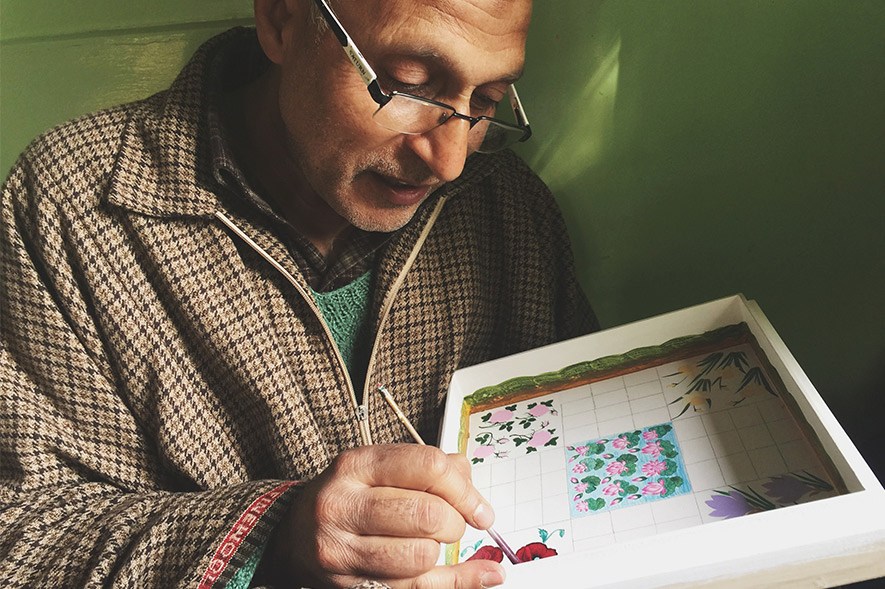

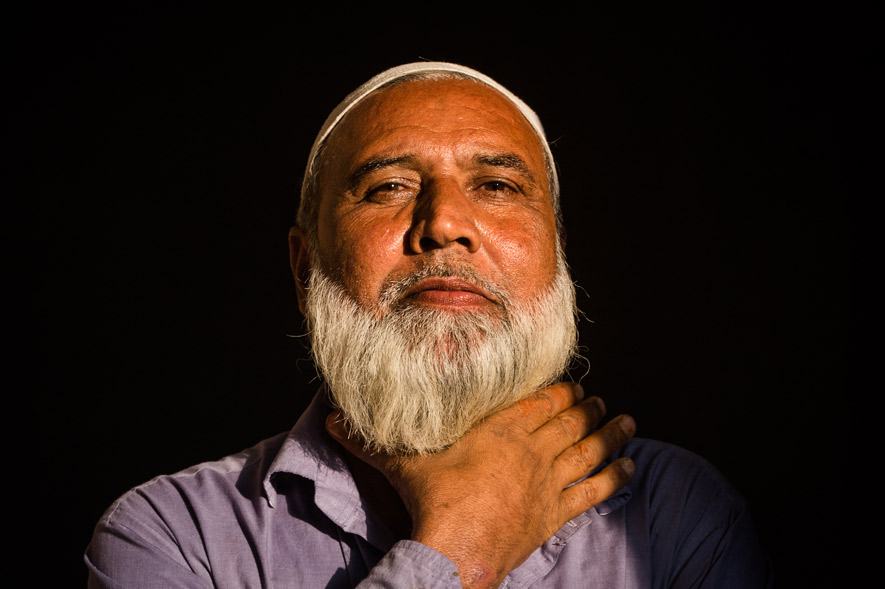

On her visit to the cemetery with Hakim saab — who’s adept at Naqqashi, the form of painting done on paper mache — she spotted a handful of men playing noughts and crosses. “They had drawn with chalk on the grave, and [were playing] with this coloured stone,” she recalls. “It’s so beautiful because there’s nothing negative about the dead. It’s just so inclusive as a thought.” It’s a sight that stuck with her — and eventually became the catalyst for a set of hand-painted board games she designed with Hakim saab, and his daughter and artisan entrepreneur Urooj Fatima.

Urooj, a 27-year-old engineer, was assigned to be Krishnan’s mentee by Commitment to Kashmir, an organisation that supports a younger generation of Kashmiri craftspeople and artisans to become independent and sustainable entrepreneurs. Krishnan remembers her initial interactions, back in 2017, with Urooj — she was polite, but reserved, not really enthused about laying aside her degree for this vocation. “When I went to Kashmir, to their studio, I realised that my task was not even one-tenth as tough as what she had set herself up against, because she would have to actually run an enterprise where the makers would be her father and her uncles,” Krishnan says. “Design had to be the building blocks of this entire business model — this business relationship within a family structure.”

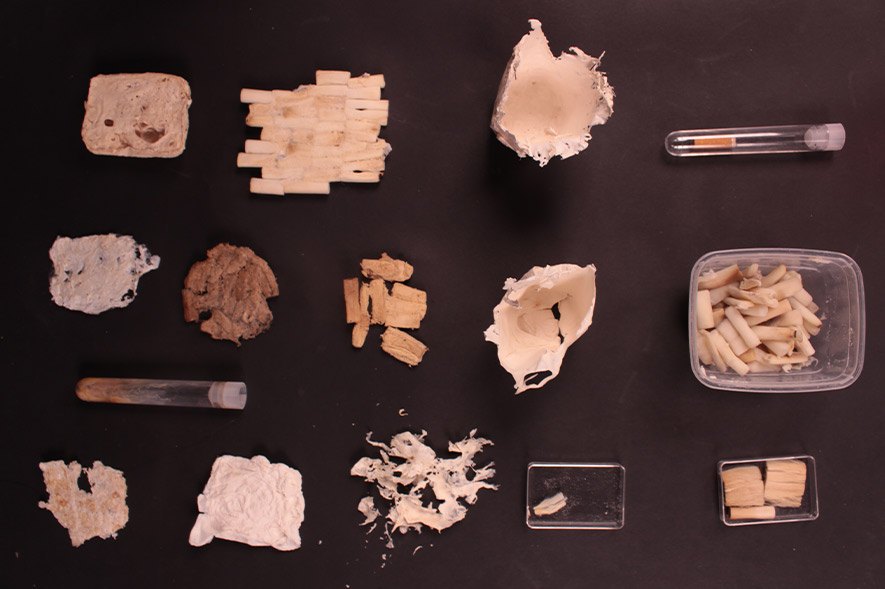

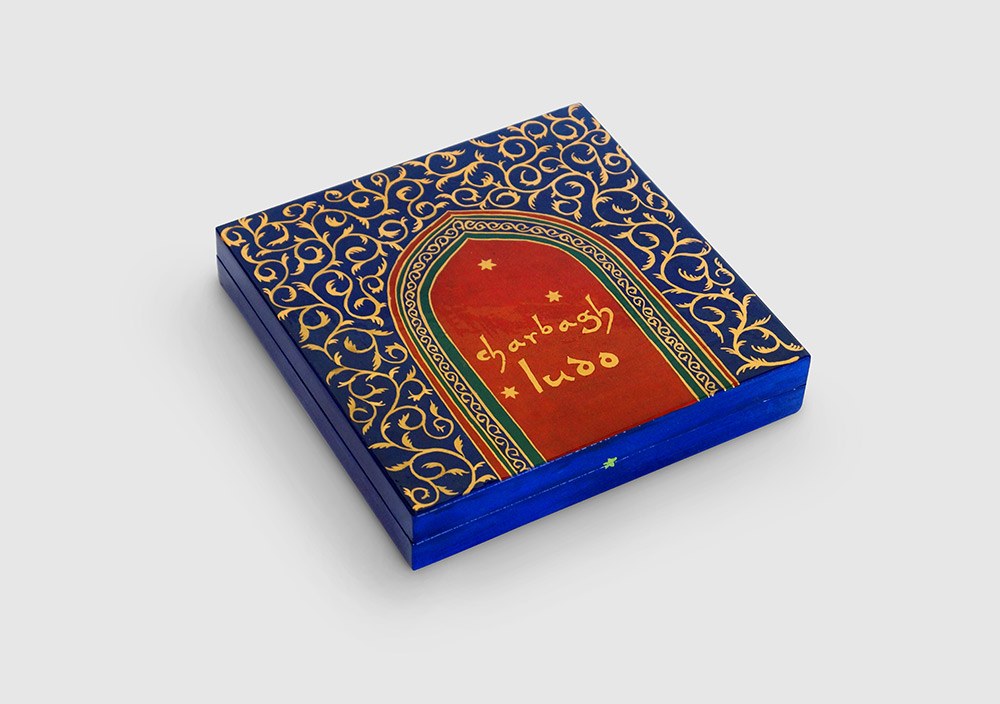

The first in a series of game designs was noughts and crosses, inspired by Krishnan’s visit to the cemetery. A mihrab — the arched niche in the wall of a mosque, whose shape also inspires gravestones — took centre stage on the box cover, while the inside board contained squares with flowers from the graves, Ashk-e-Maryam and iris.

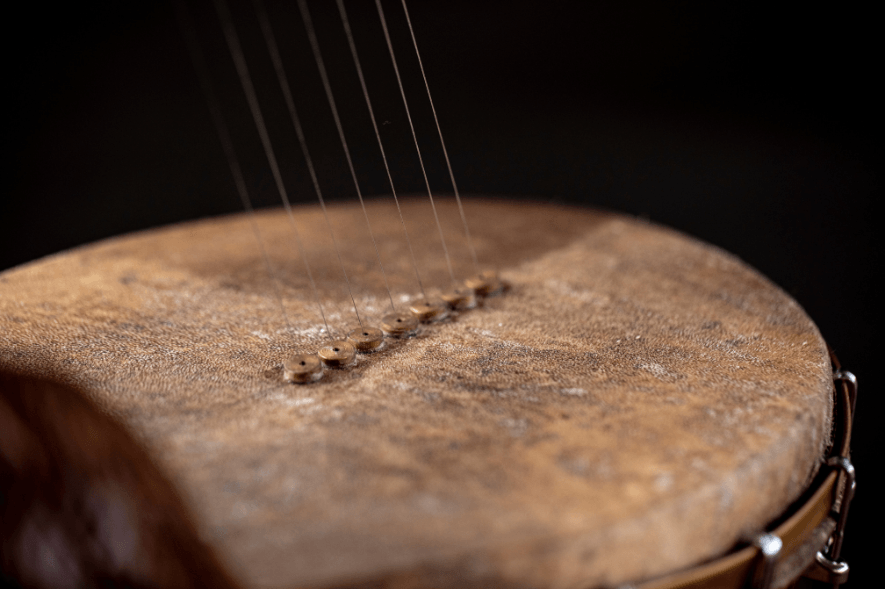

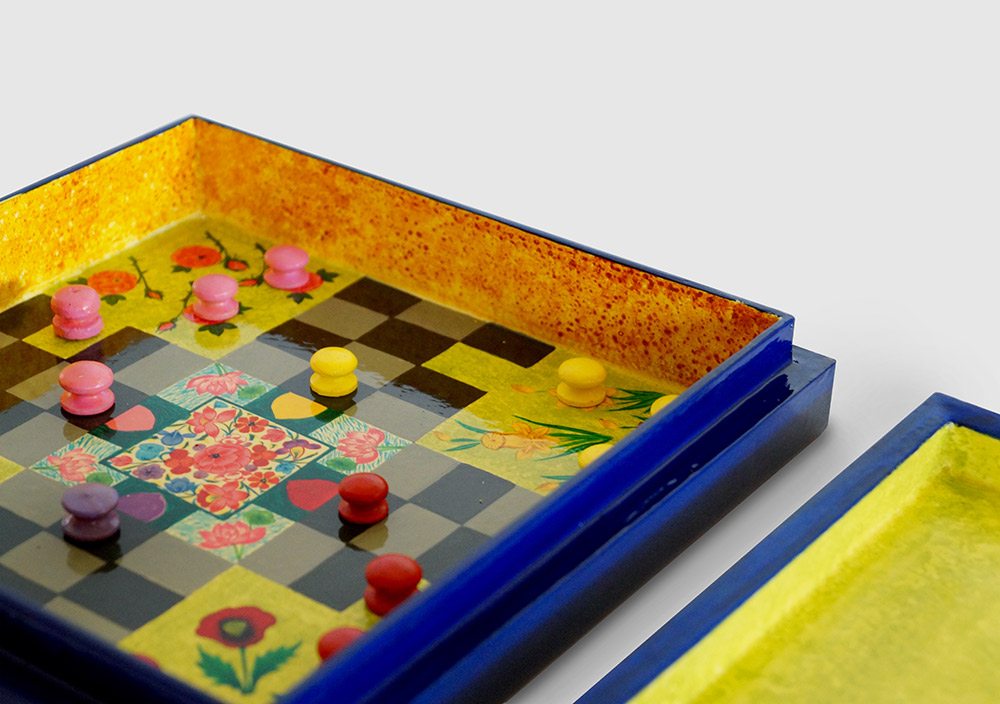

Just like the graveyards inspired the noughts and crosses set, a visit to the Shalimar gardens prompted the creation of the Charbagh Ludo set. “Ludo was very commonly played there, and we sat down thinking of what we could do with [the game]. That evening, I happened to go to the Shalimar Gardens, which I have visited a hundred million times,” Krishnan laughs. But that day, with Hakim saab, was particularly illuminating. He pointed out the social hierarchies behind the architecture of the garden — how your place at a gathering at the Gardens was determined by whether you were, say, a king, peasant, courtesan or minister. The royals would sit at the black pavilion in the centre, with their chamber kept cool by the fountains and breeze around. “That’s how the ludo set came about. It’s exactly how a charbagh garden is laid out,” Krishnan says. “When you cover all grounds [in the game] you actually reach home, to the king’s pavilion. Around the pavilion is a pond, with lotuses and fountains, and with pathways. Then there are these four flowerbeds and each flower bed has a flower from Kashmir. We’ve got poppies, irises, daffodils and roses.

During her time with the artisans, Krishnan realised that Urooj’s interest in the artform piqued when it came to business. Assessing the market viability and balancing costs with the time-intensive labour involved, and other such calculations, turned out to be Urooj’s strong suit, Krishnan explains. Together, they put a price to each of Hakim saab’s brushstrokes in order to arrive at the final cost for the Charbagh Ludo set.

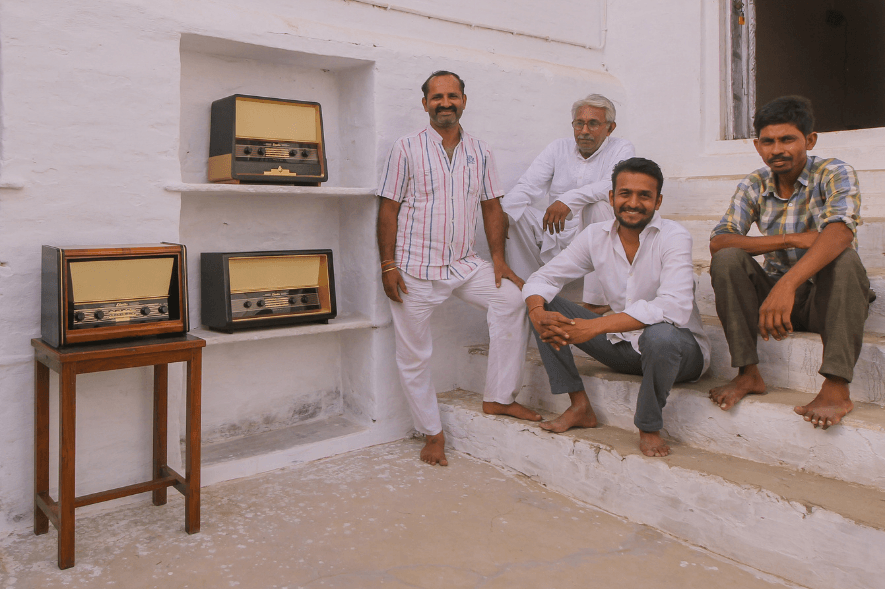

Now more than ever, while Kashmir comes up on eleven months of a harsh, government-enforced lockdown, artisans like Hakim saab and Urooj have had a slew of challenges to face. “The artisan needs to keep making [in order] to earn his money,” Krishnan says, about the importance of having a steady supply of work. “But it’s more than just earning money; it is also an occupation. Sure, I can sell a box for one lakh rupees and he doesn’t have to work for the rest of the month. Or I can actually price each box at, say, ₹2,000 and he works every day and feels happy about. Like any creative person, you want to be doing something all the time and earn from it.” The artisans play a key role in calculating the prices of their products, she says. “It’s always fairly priced so that people buy, but not so cheap that they’re short-changed. More orders [mean that] they can continuously work and also distribute work to others. So then it becomes a community, collective, activity.”

Krishnan’s work with the Naqqashis was cut short by the state-sanctioned lockdown, that’s now been on for nearly 11 months. The lockdown was accompanied by internet gags, which haven’t helped either. 2G internet, which was partially restored in January, ended what is reportedly the longest internet shutdown in a democracy. “If I send them an artwork — a PDF via WhatsApp or email — it takes until evening for them to download it. And when they send me pictures back, it takes 12 hours for them to reach me, because it takes so long to upload with 2G,” she says. Separately, there’s the added layer of COVID-19 to an already hard lockdown. While these issues persist, what’s needed are more marketplaces for the craftspeople. Organisations like Commitment to Kashmir, who are now helping the artisans digitally market their wares, need funding, Krishnan explains. “The biggest hindrance in India is that no corporate house, no funding agency, is willing to invest in Kashmir, because it’s so uncertain there. It’s been in conflict for over 30 years. In fact, Urooj and a lot of my mentees are all born in that conflict — for them, that is normal.”

The Charbagh Ludo set is ₹3,075 for a 9×9-inch box and ₹3,550 for a 12×12-inch box. The card memory games are ₹1,500 each. The noughts and crosses set is ₹1,400 for a 9×9-inch box. The games will soon be available with Commitment to Kashmir. Check @ctok.delhi and @zainabyctok for updates.

Fabiola Monteiro is Senior Editor at Paper Planes. She’s on Instagram at @fabiolamonteiro and on Twitter at @thefabmonteiro.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.