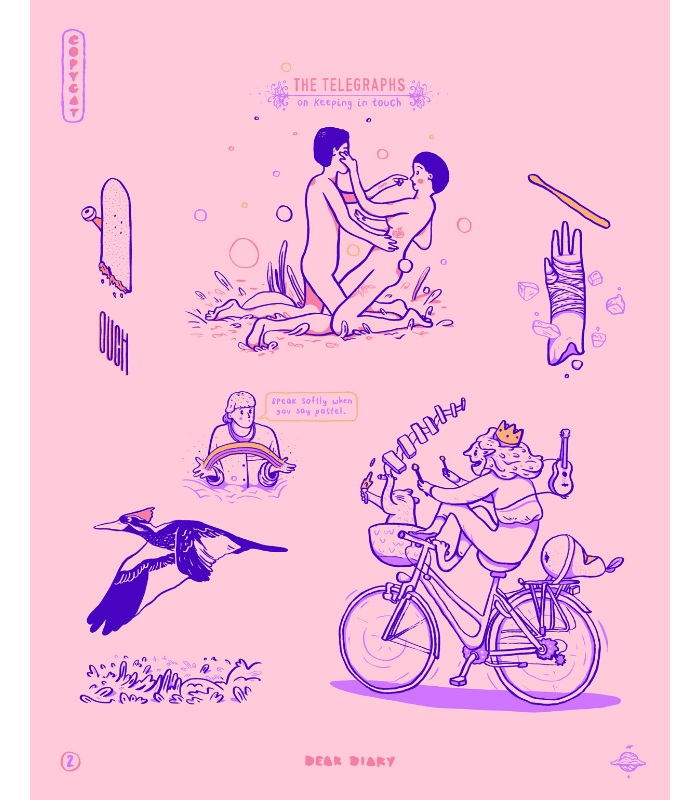

Welcome to Eye Candy, where we bring you the story behind a striking piece of art. Each time, you’ll get to feast your eyes on the work of one illustrator, graphic designer and/or visual artist, and discover details about their style, ideas and more. Follow along!

A couple of years ago, Mayur Nanda spent a month in a forest in Vermont, the USA. Each day, he would wake at 6am, run up a hill, build things, bathe in a brook, and draw at a giant table with eight other artists. This was part of GhostScout Training Camp, an art residency organised by American graphic artist and illustrator Ghostshrimp (aka Dan James aka Daniel Bandit). It was an amazing experience, Nanda says. “It made me much more goal-oriented as an artist and enabled me to work with more intent. It also inspired me to come back [to India] and take more control of my illustration career.”

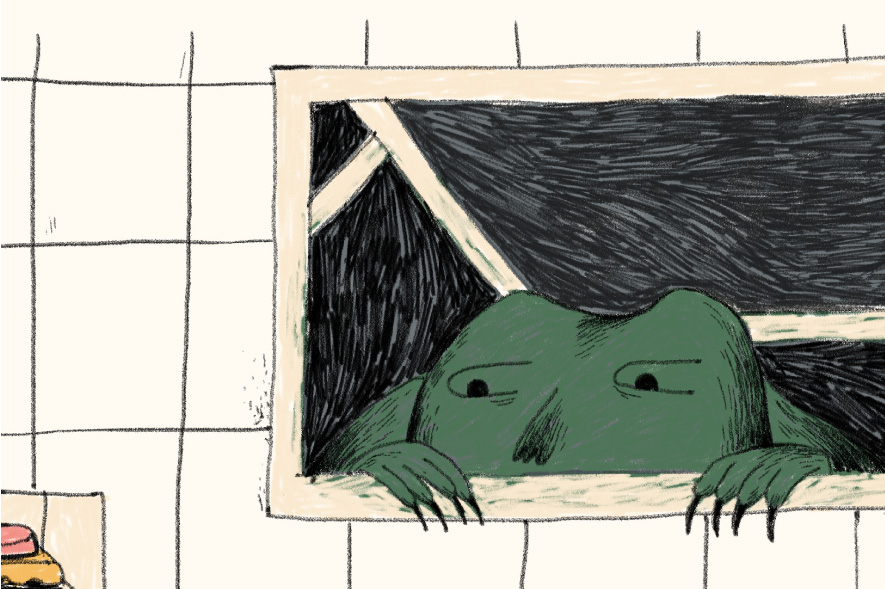

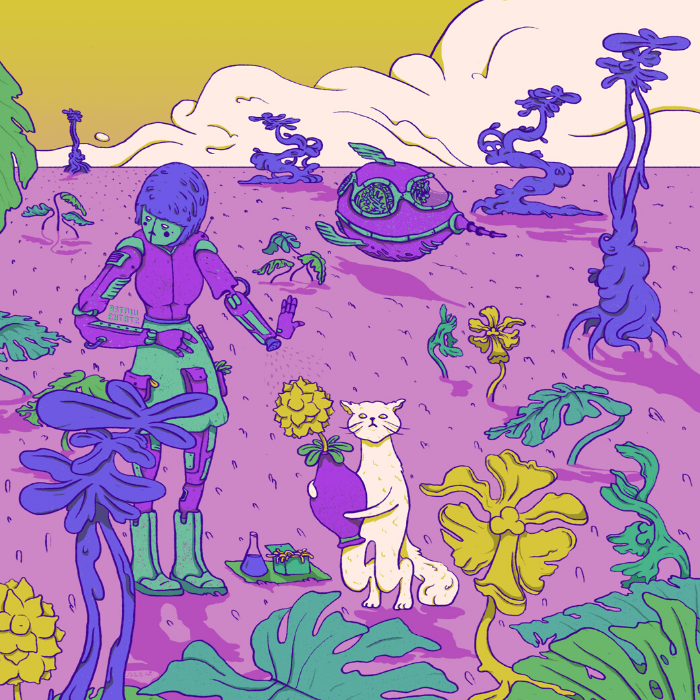

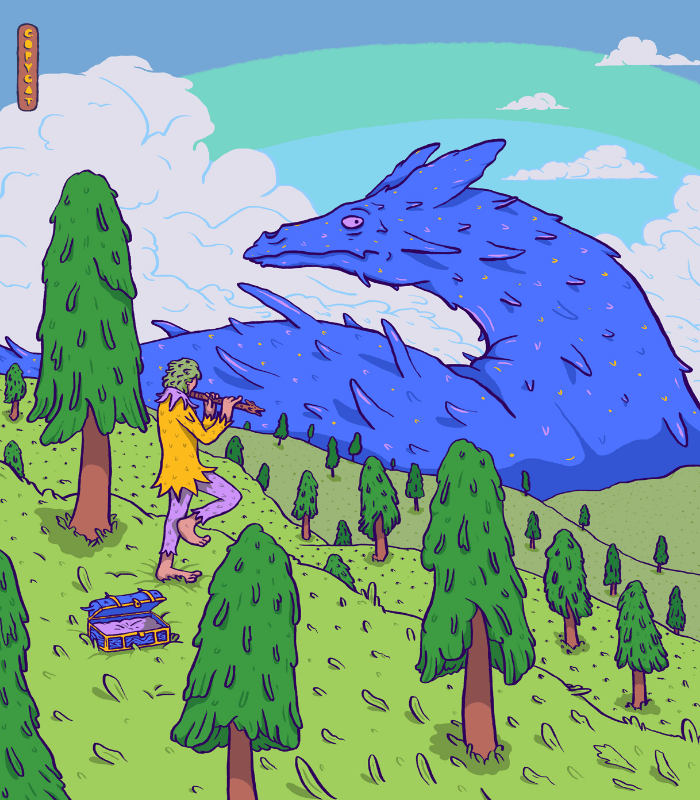

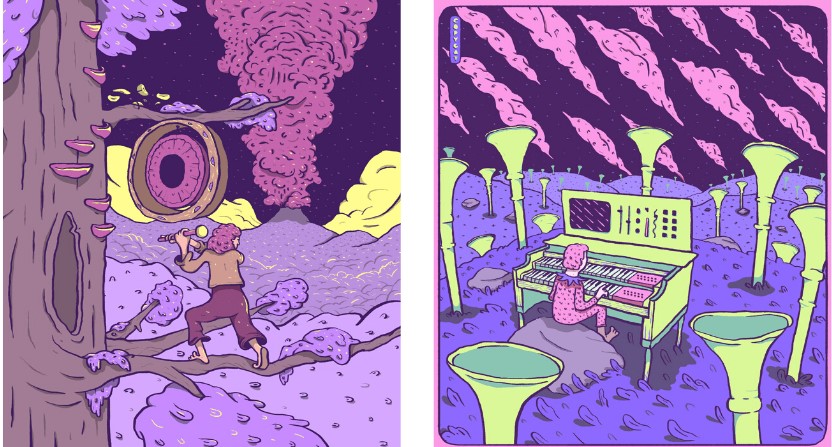

The landscapes Nanda creates are outlandish too — vast plains, foreboding mountains, all in the most surreal colours and textures. They make you want to be a part of the landscape, but it’s also eerily frightening, almost as though they are not meant for mortal beings. He describes his artistic universe as a “taffy land” after the toffee-like candy that’s made of treacle and boiled with butter and pulled until glossy. (Reader, this thrilling coincidence played no role in choosing Nanda’s work for Eye Candy.)

The Bangalore-based artist, who goes by @copycatdesign on Instagram, was working as a graphic designer until he quit his job about a year ago to pursue illustration full time. For him, having a personal voice is more vital than a style. “Someone who has good ideas can express them through film, music, or any form of art, speech or literature,” he explains. “If the message is right, then it will be clear that they’re all from the same person.” He acknowledges that his own voice is evolving organically, but the universes he creates are very distinct. Everything in them is made with one material, he explains. “Anything that you’re looking at, whether it’s the sky, a cloud, a piece of fabric or skin, or anything else, they’re all composed of the same substance, which is this element that I’ve made up. It’s soft, almost edible and sweet.” Hence, the taffy land.

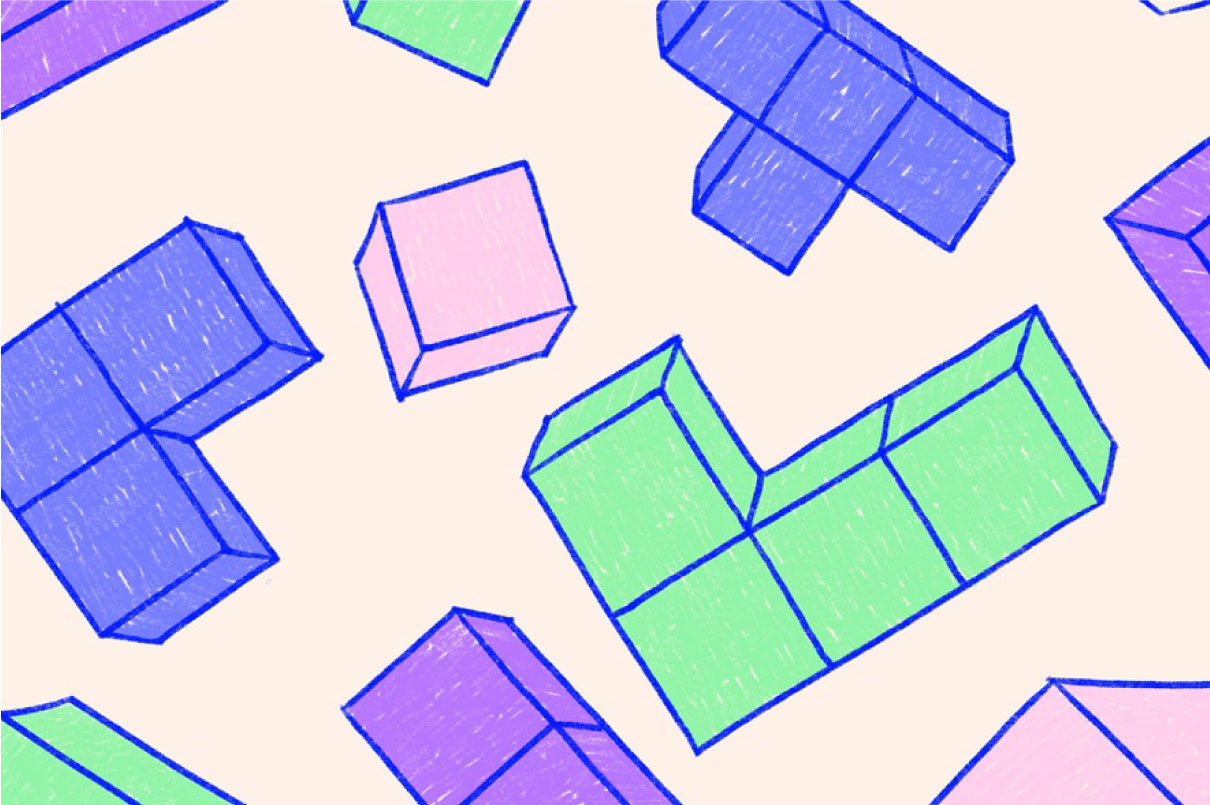

As a freelance illustrator, Nanda would like to work on art for music. For this, he says, he’s creating examples “in order to relate more to musicians, convince them that I can visualize a sound, and that I like doing that.” His series called Landscapes for Found Instruments, is something he created for this purpose. The series comprises illustrations that are all rooted in a single idea. These instruments are backed by elaborate settings and stories that Nanda visualises for them. For instance, “an ancient secret instrument has been set up in the wild somewhere, for one particular being to be drawn to it. All their lives have been leading up to this moment, where they find themselves and this particular instrument that is made for them. And as soon as they play a note on the instrument, the landscape around them starts to change.” This is also Nanda’s way of “showing my love for this dichotomy of art and music, sound and visual.”

This love finds its roots in Nanda’s ability to visualise sounds, which is a sort of synaesthesia, the condition in which one sense (for example, hearing) is simultaneously perceived as if by one or more additional senses (such as sight). “If it’s just a single note that I hear from an instrument or a whole tune, images tend to pop into my head whether or not I want them to.” This ability, almost instinctual, is what drew him to art in the first place.

Aside from this enviable gift of visualising music, it is Nanda’s ability to create transcendental landscapes and characters, at once alien and welcoming, that is particularly noteworthy. A brief pause reveals so many more layers than you’d notice at first glance.

Jessica Jani was formerly a part of the editorial team at Paper Planes. Find her on Twitter at @_jesthetic.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.