The yazh is an ancient Tamil string instrument. It’s an instrument that goes back about 2,000 years. It has been found in museums and, with its recognisable peacock head, embedded in temple sculptures. Until recently, its sound was lost. But now, 24-year-old architect Tharun Sekar has redesigned the yazh and brought back its melodic, harp-like tones.

As a teenager, the Madurai-born architect remembers becoming enamoured by string instruments — it was when he pressed play on a friend’s CD that featured tracks with a variety of guitars, recorded at a guitar festival in the USA. Over the years since that moment, he began making his own music and ultimately, his own instruments. The first one was a lap steel guitar — Tharun, who is also a part of Tamil indie band Othasevuru, decided to make one himself because he couldn’t find it anywhere else. “That process was addictive for me,” he says. “From then on, I used to make a guitar every summer vacation.”

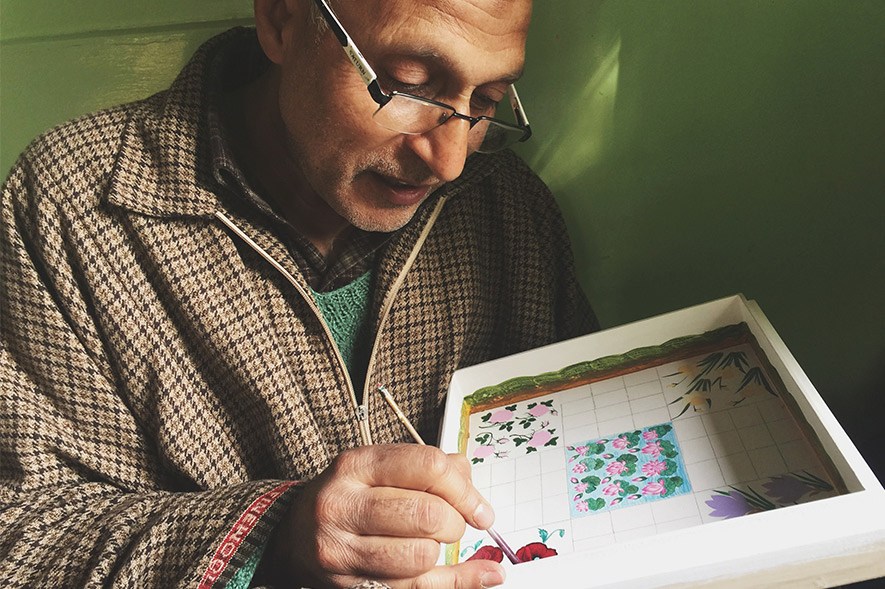

Tharun’s first brush with designing musical instruments more formally came at an internship in Auroville, while in architecture school. There, he trained under Erisa Neogy, a renowned luthier — someone who makes string instruments like guitars — for six months. Eventually, after realising he wanted to make instruments full-time, Tharun launched Uru in Chennai.

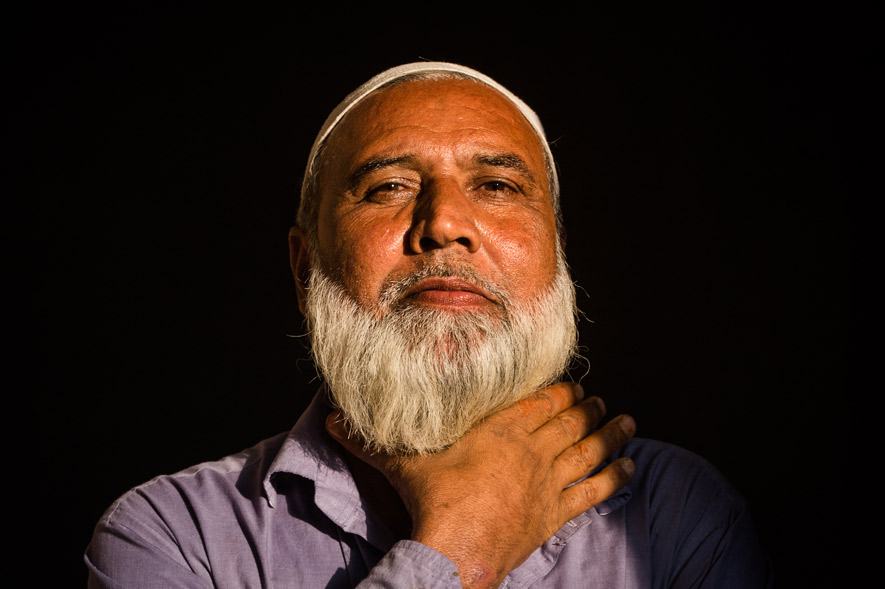

With Uru, Tharun wants to focus on bringing back ancient lost instruments. He started with the yazh, which a friend asked him to build. “I knew that there was something called the yazh, but I didn’t know what it was or how it would sound,” he says. It took a lot of research because there was no proper documentation or recording of the instrument’s sound and workings. He visited museums, pored over Tamil scriptures and Sangam literature, and thoroughly read Yazh Nool, the only complete treatise on the yazh, published in 1947.

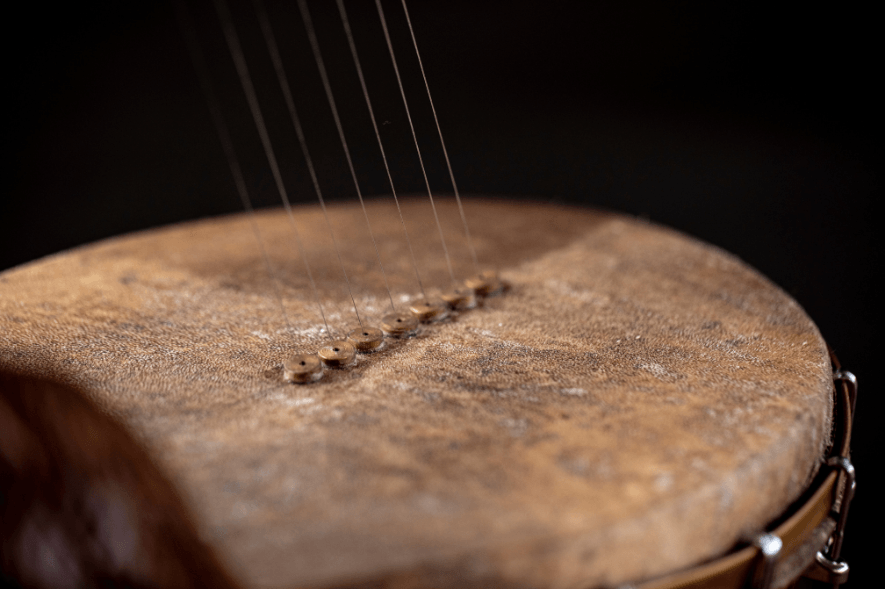

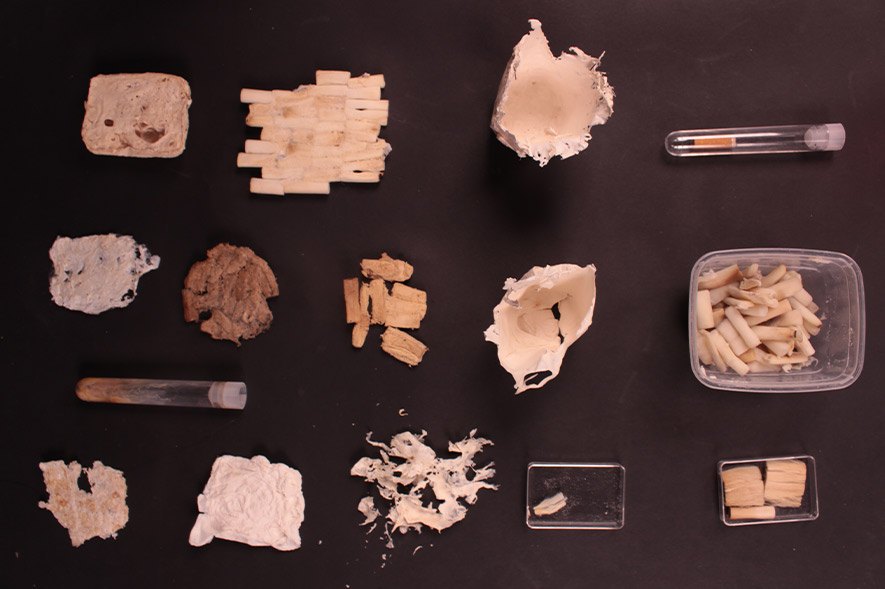

Uru’s yazh is made for contemporary times. Tharun explained how he wanted to bring it back in a functional way, so some changes to its structure were necessary. First, they standardised the tuning to the global C-major scale so that anyone familiar with the guitar could play it. The original design of the instrument had goatskin glued to the body with a turmeric-based paste. This made the process of tuning the yazh complicated — it had to be heated each time — so they added bracket hooks, like those on a banjo. A different wood — red cedar — was chosen to make the instrument lighter and more resonant, and it was scaled down in size so it could be carried around easily.

A single yazh takes around five months to make — Uru currently takes custom orders. Tharun has also been researching other forms of the yazh. While the sengotti or cenkotti yazh (the first yazh he made) is seven-stringed, there are five other versions. He is also looking into researching other ancient instruments that he could rebuild, like the panchamukha vadyam, or the five-faced drum. At the moment, the main goal is to make the yazh more affordable and available to a wider audience. It is currently priced at a lakh and a half. Meanwhile, Tharun continues to play the yazh, play in his band and make the instruments his band plays too.

Jessica Jani was formerly part of the editorial team at Paper Planes. Find her on Twitter at @_jesthetic.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.