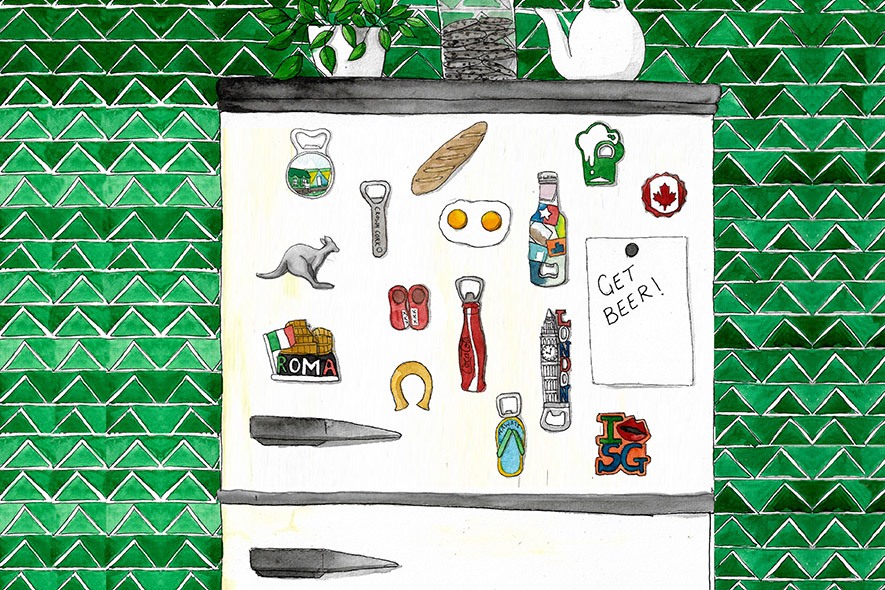

Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a monthly column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world.

Before Le Creuset brought the cocotte into common kitchen usage, the word was used to describe alternately a rooster, or a person who accepted payment for sex. Cocotte, French for prostitute and for a crowing species of poultry with a comb and wattle, is now almost entirely a family-friendly word, albeit loaded with Pavlovian responses tied to the sounds and smells of browning and braising meat in a Dutch oven.

For serious cooks, Le Creuset or Staub cocottes, vividly enamelled, tightly lidded cast iron saucepans have reached peak cult status; they are unarguably objects of high design and high desire. Cocottes move fluently from stovetop, where meats and vegetables brown beautifully and evenly, into the oven where tough cuts become tender, and the complex array of browned flavours from their Maillard reactions are allowed to develop further, infusing the braising liquid, to create richly flavoured sauces, gravies, and stews. This is because immensely durable cast iron has two key properties that, in combination, are unmatched by most other cooking materials — the ability to heat to very high temperatures (helpful for browning), and the ability to retain heat well (ideal for braising, baking, roasting, and so on). Which is perhaps why the histories of lidded iron saucepans in our kitchens can be traced to the Iron Age, the Han Dynasty, and the Industrial Revolution.

Human beings have been using bare cast iron since the beginning of the Iron Age. In China, archaeological evidence suggests it was used in weaponry, pagodas, ploughshares and artefacts as far back as 6th century BCE — cookware, in particular, came around during the Han Dynasty, around 2nd century BCE. Most of the Western world only discovered the wonders of cast iron as cookware as recently as 2000 years ago, most likely through Chinese technology transmitted via the Silk Route. Early cast iron cookware sounds witchy: the cauldron was a cast iron pot dangled above a fireplace or in a hearth, some pots had “legs” to lift them above burning wood or coals, and were called spiders.

The predecessor to today’s bright and beautiful aspirational cocottes had both. The first one was designed by an enterprising Englishman named Abraham Darby the Elder whose immediate descendants played key roles in the Industrial Revolution. In 1704, Darby visited Holland and noticed how the Dutch used sand (rather than loam or clay) to cast brass vessels. He decided to apply the same technique to a cheaper, but equally resilient and practical material — higher carbon iron. On page 46 of the Reference Index of Patents of Invention (from 1617 to 1852, by B. Woodcroft, With Appendix), somewhere between the applications for Double Hand Bellows and Lamp with Globular Glass is Darby’s 1707 CE application for a patent for Casting Iron Bellied Pots in Sand Only.

A case is made for it with these words: “by his study, industry and expense, [Darby] hath found out, and brought to perfection, a new way of casting iron bellied pots […] in sand only […] with ease and more expedition […] their cheapnesse may be of great advantage to the poore of this Our kingdom.”

Darby’s Dutch oven could also hold coals on its lid, intended for cooking outdoors or in a fireplace. This made it hugely popular in Europe and Colonial homes in the US. With the invention of the stovetop, vessels could have flat bottoms, placed directly on an indoor flame without threatening to extinguish it, so the Dutch oven could now lose its feet and arced hanger. By the 1760s, metal vessels in Germany were being lined on the inside with enamel for practical reasons — to prevent rust, or to avoid off flavours that often come from cooking in iron or copper. By the 1860s, the idea had caught on in American foundries.

In 1925, almost 165 years after enamel first lined metal hollowware, two Belgian men in northern France’s Fresnoy-le-Grand, a hub for iron and sand trade, started a foundry creating Dutch ovens coated with flame orange-red enamel. Caster Armand Desaegher and enameller Octave Aubecq, the founders of Le Creuset (French for “the crucible”), chose the colour to evoke lava, or the foundry’s molten iron as it cooled and set in wet sand casts. A Dutch oven thus coated with enamel is technically called a French oven, but somehow, the latter just doesn’t have the same ring to it, so that description’s never stuck for Le Creuset (or for Staub, or Lodge, or any of the other later manufacturers of enamelled cocottes).

While volcanic orange-red is still the most recognised colour for Le Creuset — production line workers at the still-active Fresnoy-le-Grand foundry wear T-shirts of the colour, as seen in this stunning photo essay in The Guardian — its cylindrical, straight-walled, lidded saucepan has become an icon of kitchen design, proving that high form and high function can co-exist without conflict. Each piece is quality-checked by 15 people for flaws — any piece that is even slightly flawed is re-melted.

Le Creuset now sells its enamelware in about 100 colours, and favourites differ by country — France loves the original flame hue, Japan loves pastels, and Americans like primary colours. But the cocotte’s versatility beats its enamelled spectrum. While it is known for its efficacy in searing and braising, the cocotte works just as well as a vessel to roast, bake, fry or boil. This means it’s as good for dum biryani as it is for donburi.

Julia Child, who popularised the cocotte in North America (and was also a fan of the pressure cooker), loved the ‘true red’ one, designed by Italian modernist artist Enzo Marie. This, her “soup pot”, is part of an exhibition at The American Museum of Natural History, a gift from the chef herself. Marilyn Monroe was a fan of the (since discontinued) Elysees Yellow colour. Her 12-piece set of enamelled cast iron Le Creuset cookware sold for over $25,000 in 1999. In the US, a standard 4.5-quart cocotte typically retails for about $300. Darby with his patent application pitch stating cheapnesse for the poore might roll his eyes, but for Le Creuset cocotte obsessives around the world, the price tag hardly matters.

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @roshnibajaj.

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.