Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a monthly column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world.

A bowl, a club and some forearm strength – all that human beings need to mash, crush, squish, bruise, grind, paste, shred, smash, pound, or pulverise.

The mortar and pestle is one of our oldest kitchen tools. This utensil gets its first mention in the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus, a medical scroll composed in 1550 BCE – but evidence of its use goes back to 35,000 BCE. Early homo sapiens used it not only to de-husk cereals, but also to process meat, fruits, nuts, leaves, seeds, and bark. Turns out, now, well into the 21st century, when we can get Alexa to make us coffee, we continue to use the mortar much in the same way as our Late Pleistocene ancestors did.

With some specialisations, of course. The mortar (from classic Latin’s mortarium, “vessel for pounding”) and the pestle (from pistillum, “pounder”) have each diversified and adapted over time, regions, and cultures to suit specific cuisines and their needs.

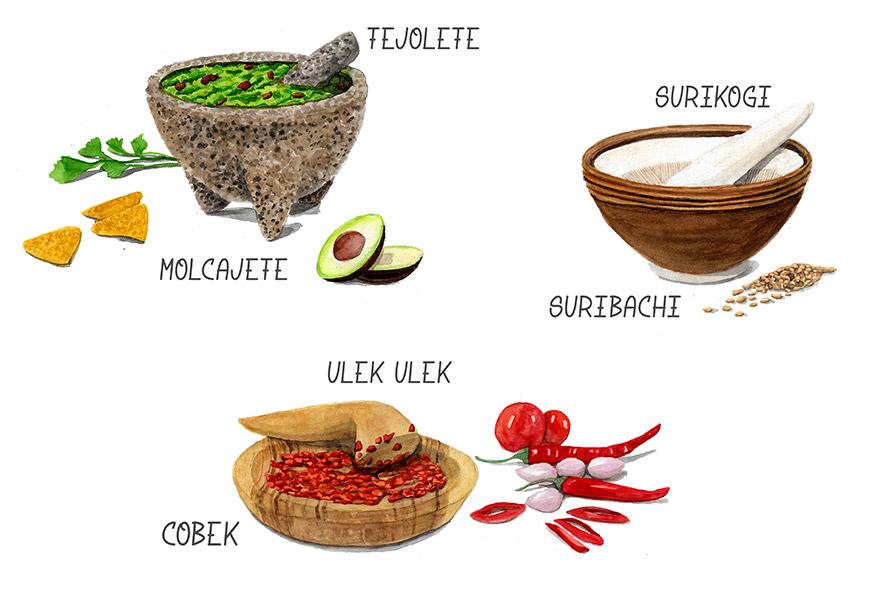

Allow me to illustrate. The absorptive molcajete – fashioned from coarse ancient basalt by the Aztecs and the Maya, still used in modern Mexican restaurants to roughly crush avocados into guacamole – will not work for the Italians. A proper creamy (and not oily) pesto needs a smooth marble bowl and a pestle made from the softer olive wood to gently bruise the ingredients’ cell walls, release their aromatics and emulsify the sauce. In Thailand, nothing pounds the ingredients of a curry paste better than a granite khrok and saak – but it’s hardly advisable to use anything but an earthenware mortar and wooden pestle for delicate Thai salads such as a som tam or a tam som-o.

Clearly, while the kinetics of the mortar and pestle remain roughly the same across the world, relying heavily on weight and gravity, its results are determined by material. Pharmacists and bartenders prefer smooth, inert easy-to-clean glass, ideal for precise trituration or muddling without cross-contamination. The Japanese kitchen has a specific kind of mortar and pestle to grind sesame seeds. To this end, their delicate, shallow earthenware suribachi bowl with its unglazed ridged insides works perfectly with its accomplice, the soft sansho wood surikogi. This construction comes closest to the Eastern European lidded clay bowl makitra, in which a makohon, a pestle with a rounded, ball-shaped bottom, is rolled around to crush poppy seeds or cream cake batter.

Then there is the matter of size. In Africa, knee- or thigh-high solid wood mortars, and pestles as tall as the humans who wield them, are so traditionally ubiquitous, they are now a fundamental part of birth, wedding, and funerary rituals. Their constant, consistent, comforting thump-thump also serves to lull the household’s babies to sleep while mothers pummel piri-piri or fluff fufu. In Spain’s Navarra region, small decorative mortars made from old grapevines are tableware, used to grind salt and pepper. A traditional Indonesian sambal, worked on in the smooth, dish-like cobek by a palm wood ulek ulek, tastes distinctly different from anything made in a food processor.

In India, where every regional cuisine has distinct spice mixes, batters, and ground meats, we seem to use every kind of material: East Indian bottle masala needs the wooden okhali with a long pestle; the fluffiest idli batter comes from the Tamil stone aatu kallu; turmeric is pestled for weddings with brass on brass.

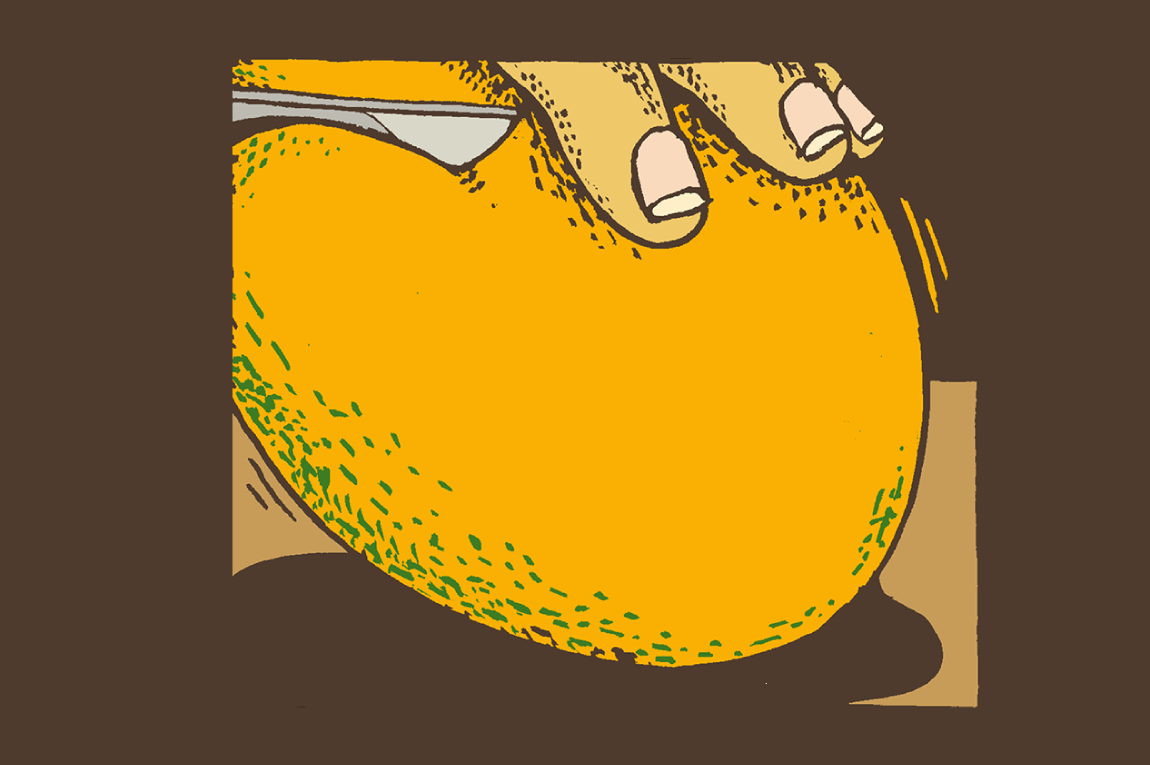

Which then proves that when it comes to the physics of the mortar and pestle, thirty-seven thousand years of technology hasn’t surpassed good old elbow grease. Modern mechanised pestles still make an efficient, low-effort, but poor substitute. They exist in spice and grain markets across the country (Lalbaug’s Chivda Galli in Mumbai offers curious visitors a close look). Serious and seasoned cooks, however, maintain that machines almost never offer the same control over texture, nor the guarantee of maintaining the temperature of ingredients to prevent flavour compounds from becoming oxidised and acerbic. For a fresher flavour and a livelier texture, we still need the symbiotic prehistoric partnership of this bowl and club, helped along with a bit of muscle.

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @roshnibajaj.

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.