Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a monthly column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world.

When life gives you lemons, make lemonade. To make it well, use a lemon squeezer.

Human beings have found many ways to press citrus fruits: we roll them between our fingers or palms, we put them in hinged contraptions that resemble garlic presses or nutcrackers, we use MacGyver-ed handheld reamers such as forks and whisks, and we put them in 600-watt machines. But of all the mechanisms we can use to burst juicy cell walls, nothing is as elegant as the lemon squeezer.

Lemons may have originated in Assam, but they found their way to West Asia around 700AD, and were imported in large quantities to Turkey in the 17th century because of the massive popularity of a drink called sherbet. This was no ordinary lemonade — honey, water, and lemon juice were chilled with ice and and perfumed with violets, ambergris, and musk. And so, for purely practical purposes, the earliest known lemon squeezers in the world were designed in Kütahya in Western Turkey, in the early 18th century.

Used as they were in Turkish courts and baths, squeezers became ornate. Kütahya was known for its kiln products, so a juicer could be made from delicate white ceramic painted with cobalt rosettes and floral sprays. These Ottoman ceramic squeezers are now considered fine specimens of product design, art, and history, and feature as collectibles at auction houses, selling for tens of thousands of pounds.

Three centuries later, modern-day lemon squeezers are structurally identical to the Kütahya ones – an upright conical reamer fixed into a wide shallow bowl which in turn has a spout to pour out the juice. The best ones have little blunt teeth at the base of the reamer that let juice go past, but not seeds. Those of us who grew up in India in the ’80s or ’90s may remember how ubiquitous this was in our kitchens, more likely made of moulded or pressed greenish glass, steel, aluminium, or plastic.

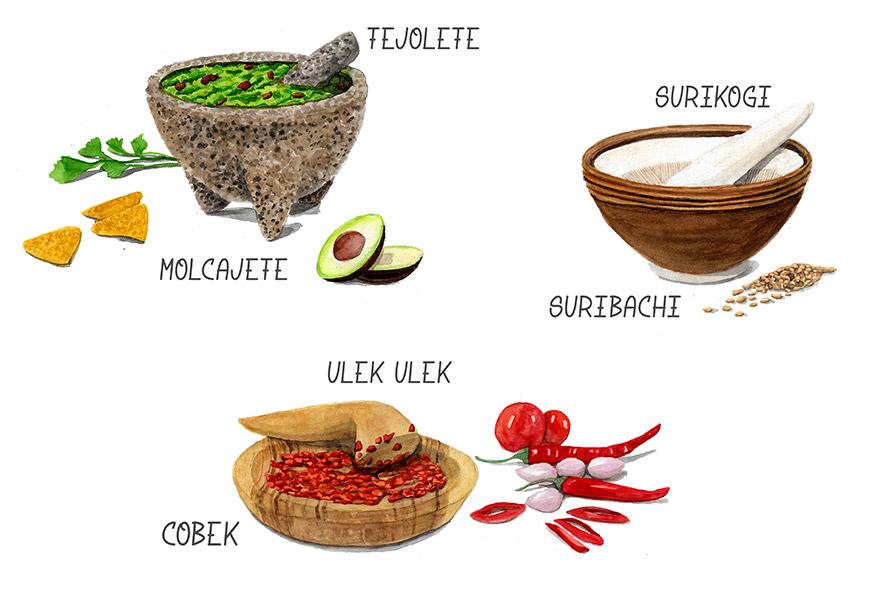

Garlic press-style juicers may be having a moment in Indian homes, but they’re also rigid in many ways. They do nothing for lemons that are too big, too small, too soft or too hard. The lemon squeezer is unfussy — it works with any size of citrus at any stage of ripeness. Halve a lemon, place the centre of the cut side onto the tip of the reamer, press and rotate, until the fruit has yielded all of its juice, then repeat. It’s a tool that maximises extraction, minimises waste, doesn’t create a mess, and once human muscle memory kicks in, lemons can be juiced with assembly-line efficiency. Like the mortar and pestle, it requires us to press into our food with our body weight, and also like it, it takes many forms in many materials, but its simple elegant design is hard to improve on.

Not that we haven’t tried. The simple squeezer has received inordinate amounts of fascination from humanity. Between 1880 and 1910, the United States Patent and Trademark Office received a little under 200 registrations for lemon squeezers. A heritage museum in Texas has a permanent reamer collection, featuring over 2,300 reamers, some of which look like cowboys, jesters, angry aunts and Benjamin Franklin. We might even be a little bit obsessed, especially in the US: there is a Facebook group that celebrates the squeezer as a collectible; and way before Facebook, in 1987, the LA Times featured a story about reamer collectors.

But perhaps the squeezer to rule them all is also the most subversive, the most controversial, and the most famous of all squeezers. In the late ’80s, product designer Philippe Starck was eating calamari on the Amalfi Coast, thinking about a design solution. Alberto Alessi, president of Alessi, the Italian design brand that Starck collaborates with, had asked him to come up with a tray. A few weeks prior, they’d had a brief discussion on how lemon consumption was on the rise in Italy. Starck looked at his plate and realised he didn’t have any lemon to squirt on his seafood. While waiting for his juice, Starck starting doodling on his pizza-joint place mat, starting with a calamari which, in stages, morphs into a citrus squeezer. He mailed the place mat to Alessi, who says it was one of the most amusing designs he’s manufactured. As Alessi describes in a YouTube video, the Juicy Salif flipped the notion of form follows function, and by deliberate design looks better than it works. It’s impractical and makes a mess, spraying juice all around its feet. What this monstrous but also stunning three-legged aluminum spider from another galaxy did do is mark the beginning of a post-modern design movement that wasn’t limited to lemon squeezers. Its iconic design and its ability to spark debate has earned the Juicy Salif a spot at the MoMA.

Other designers have attempted to make the squeezer their own without veering towards the impractical. Designer Graeme Davies’ ‘Catcher’ for Joseph Joseph is a handheld reamer with a colander cup to catch pips and German homeware design firm Koziol created the Ahoi, a stackable juicer shaped like a paper boat but made from plastic, where “both the bow and stern can be used for pouring”.

Starck believes that The Juicy Salif has done its job — it is intended to be more a conversation starter, less a mere piece of kitchen equipment. As squeezers go, it’s a lemon.

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @roshnibajaj.

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.