My window looks out over a garden, where a bright turquoise-backed little bird has been making a frequent appearance. It sits on the power line that cuts across the garden, a garden that I’ve looked out at more or less every day for about 15 years. I’ve watched branches wildly dancing in the whooshing wind, the trees turn resplendent shades of neon during the rains, and buttercup yellow copper pods add a bright spot to this view every April. I’ve spent hours staring out this window — mulling life, sipping chai, skipping deadlines — and yet, I can’t be sure that the white-throated kingfisher I’ve just spotted has ever stopped by before this lockdown commenced. It’s not an uncommon bird in Mumbai — white-throated kingfishers are only one of about a dozen stunning birds commonly found in the city. Maybe I just hadn’t tuned into its quavering call before.

As humans, it’s incredibly common to want what we can’t have. The grass has always been greener. In psychology, ‘scarcity bias’ involves the value of a product increasing as a result of it being scarce. In microeconomics too, a greater demand than supply results in soaring prices. Which is all to say, now that I’m home, without the option of going on a hike in a sun-dappled forest or on a walk along the beach — things that I could’ve, should’ve, made more time for in a pre-pandemic world — I want to even more.

On an episode of the new Sugar Calling podcast, the acclaimed travel writer Pico Iyer discussed the idea of impermanence, both in our human lives as well as in nature. “The cherry blossoms are such a good example of that because it’s the fact they only last for 10 days that makes them so beautiful. And if they lasted forever, we would take them for granted,” he said. It’s an example that stuck with me in these COVID-19 times because of how much I’ve taken my interactions with nature and the outside world for granted. Additionally, there’s a predictability to this idea of impermanence that’s incredibly reassuring too — a hot summer giving way to a muggy monsoon, a crescendo in birdsong during breeding seasons, that mangoes come in April and strawberries in December. Like clockwork, it’s a sense of surety in the natural world that, at this moment, is glaringly absent from our lives.

With our lives upended by COVID-19, we have no real bearings on when we’ll be able to go tiger-spotting in a national park, or inhale the heady scent of pine trees up in the Himalayas, or encounter clownfish and whale sharks while scuba diving. And yet, even though we may be barred from getting out, we’re finding new ways to bring the outside world in (albeit, via our screens). Airbnb Experiences lets you meet rescue goats on a farm in a corner of the USA. Marine Life of Mumbai takes you tidepooling across city shores via Instagram stories. The Bombay Natural History Society’s Conservation Education Centre has been conducting insightful webinars — on bird call identification, an introduction to dragonflies, on summer flowers — via Zoom. My work breaks while working from home have involved watching short documentaries like this recent one on the vulnerable western tragopan.

In real life too, so many of us have been paying more attention to the birdsong that’s in full blast without our human-powered din — a friend, whose sleep cycle has gone for a toss during the lockdown, knows it’s time for sunrise when he hears purple sunbirds and common tailorbirds outside his window. Another has red-vented bulbuls making pit stops at her terrace. On my Instagram feed, I’ve seen stories of grey hornbills at balconies in Mumbai, and photographs of a flamboyance of flamingos making its arrival in the city (the migrant birds were delayed this year but the numbers are reportedly 25 per cent more than last year).

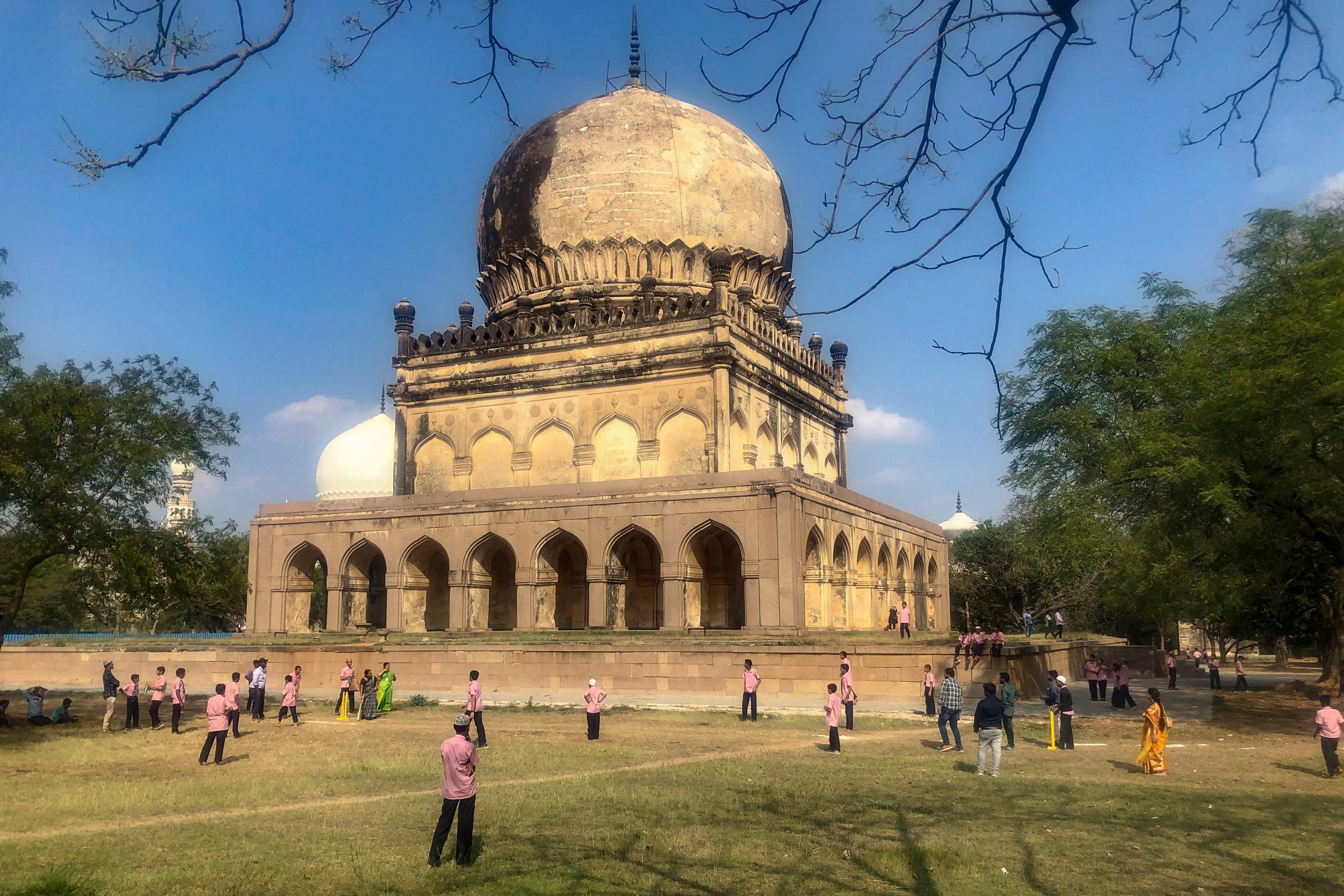

My interactions with nature and the wild have left me equal parts incredulous and grateful for this big planet we call home. In this showreel of my life, I would include peering up at ferns sprouting on mountainsides while road-tripping in Sikkim, finding ammonites likely formed millions of years ago in Himachal’s high-altitude Spiti Valley, learning of the interdependence between figs and fig wasps on a tree walk in Mumbai’s Sanjay Gandhi National Park, and spotting dolphins from a secluded beach in Mararikulam, Kerala. These aren’t, by any means, earth-shattering sightings or discoveries — but they’ve definitely made their mark on my city-slicker brain.

In fact, our interactions with nature have shown a remarkable impact on the way our brains work. Science has shown that nature is healing, a fact we’ve known long before we had the data to back it up. Noteworthy though, is that you don’t necessarily have to be in nature for it to be good for you — soaking in our wide, biodiverse world via a screen does the trick too. In a story in National Geographic magazine, writer Florence Williams points to a study in which Korean researchers used functional MRI to watch brain activity in people viewing different images. “When the volunteers were looking at urban scenes, their brains showed more blood flow in the amygdala, which processes fear and anxiety. In contrast, the natural scenes lit up the anterior cingulate and the insula — areas associated with empathy and altruism. Maybe nature makes us nicer as well as calmer,” she writes.

This is good. It means that, even though we may not have access to our parks and beaches, gazing out at a garden — from a window or a web browser — to rekindle a long-distance, voyeuristic relationship with nature may just be the tonic we need to get through these times.

Fabiola Monteiro is Senior Editor at Paper Planes. She’s on Instagram at @fabiolamonteiro and on Twitter at @thefabmonteiro.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.