Take a minute to mentally scan the space you’re in; from shell to shelf, and possibly self. Chances are you will spot at least one piece of design that’s inspired by the jaali — a perforated screen, traditionally crafted from stone or wood. At the most basic level, you’re likely to see it along common and service areas in apartment buildings. Then as a line of control — hexagons in black, yellow, green — for the world’s messiest intruder: the pigeon. It might be in a forgotten piece of jewellery you scored at Dilli Haat ages ago, or hidden in plain sight on furnishings in your living room. The 16th-century architectural device has slipped through space and time, evolving across materials and technology, to become part of India’s everyday design vocabulary.

Before we explore its current status as a cultural symbol — an overused one, some may argue — let us take a minute to marvel at its original function. As a passive cooling element, it offers shade from the harshness of the sun, while encouraging natural lighting and air circulation. “The jaali epitomises the subcontinent. It’s a smart device before smart technologies happened,” says Latika Khosla, Founder-Director, Freedom Tree Design, a colour- and trend-based studio in Mumbai.

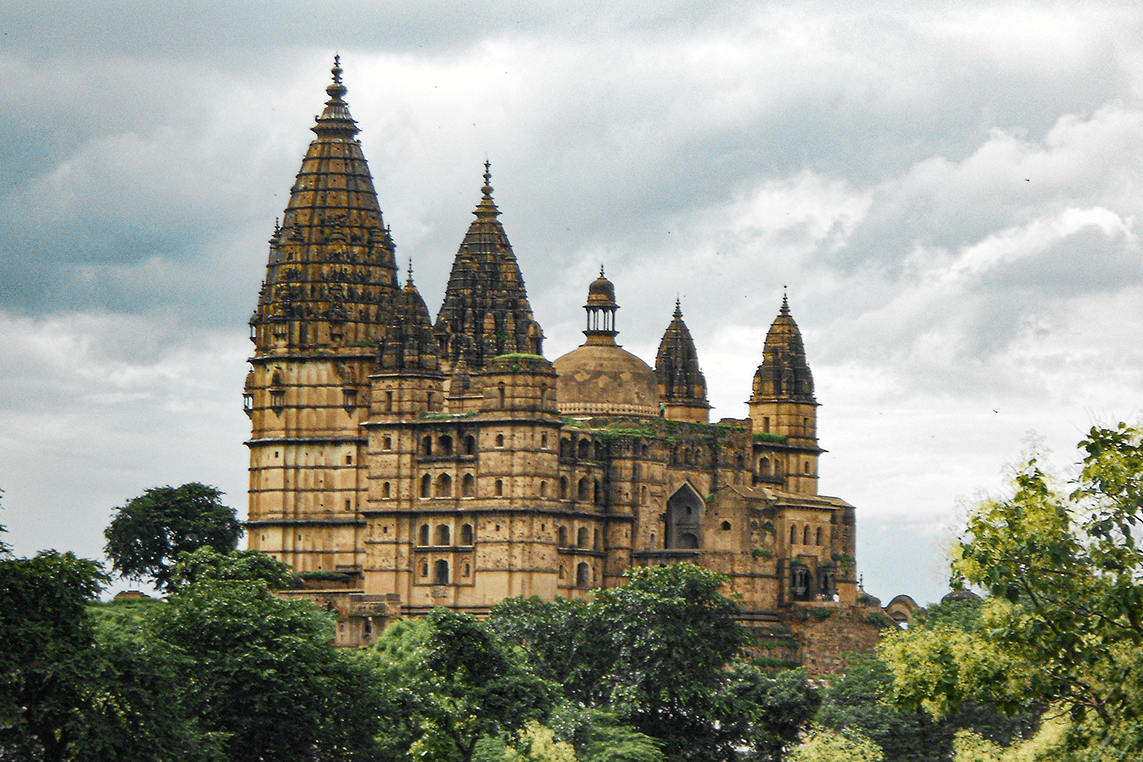

The Urdu origins of the word (jaal refers to a net), along with its prevalence in Mughal architecture, suggest that the jaali was an import of the eponymous Empire (1526-1761). Although, according to an article in Architectural Digest, carved apertures existed in India, albeit in rudimentary forms, as early as the 8th century — at the Kailasa temple in Ellora, Maharashtra, and the Pattadakal temple complex in Karnataka.

In keeping with social norms of the time, the jaali also served as a purdah, initially segregating gender-specific areas and eventually demarcating the personal from the public. It allowed inhabitants a view while ensuring privacy. “The jaali gives me the sense of the forbidden and sensuality, that not all is revealed… In that respect, it is a representation of intimacy. If you cross the purdah or jaali, some great concept or emotion or person gets revealed,” elaborates Khosla. It is this sense of discovery that many present-day designers bank on to create unique circulation schemes in cookie-cutter retail formats. Asha Sairam, Design Principal at Delhi-based architecture and interior design practice Studio Lotus, likens it to the concept of a bazaar with its “intimate pockets offering a personalised retail experience.”

Design is in the Detail

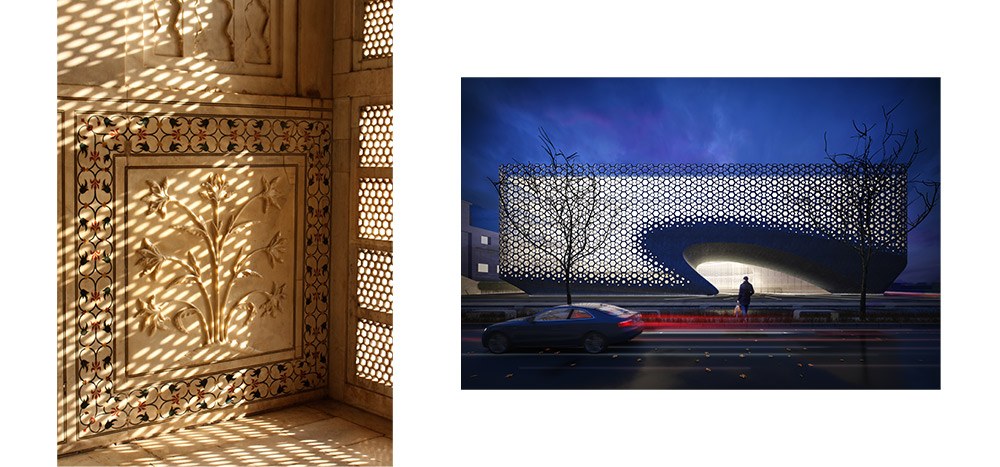

Visually, the play of positive and negative space, of light and shadow, lends a flirtatious softness to an otherwise solid surface material development. To understand the jaali’s aesthetic, we need to look at Islamic design. Given the religious philosophy’s non-figural mandate, craftsmen drew on principles of art, history and mathematics to evolve what we now know as Islamic geometric design. In essence, a pattern is built on tessellation — a simple geometric progression — of a single form. The repetition is said to be representative of the infinite nature of the divine. Geometry was often coupled with calligraphy and botanical forms.

At the Taj Mahal, the marbled enclosure around the royal couple’s cenotaphs is believed to showcase the jaali at its finest. Parchinkari (a form of inlay work known as pietra dura in Italy) in semi-precious stones features along the octagonal screen that took a decade to complete. Crenulations, kanguras, acanthus leaves and vase-like elements are all part of the intricacies of this creation. Conversely, the jaali-work at the Naulakha Pavilion in Lahore Fort, Pakistan — also built by Shah Jahan as a summer retreat — is an exercise in simplicity. It sees the hexagon repeated across planes to render myriad mesmerizing patterns.

Present Continuous

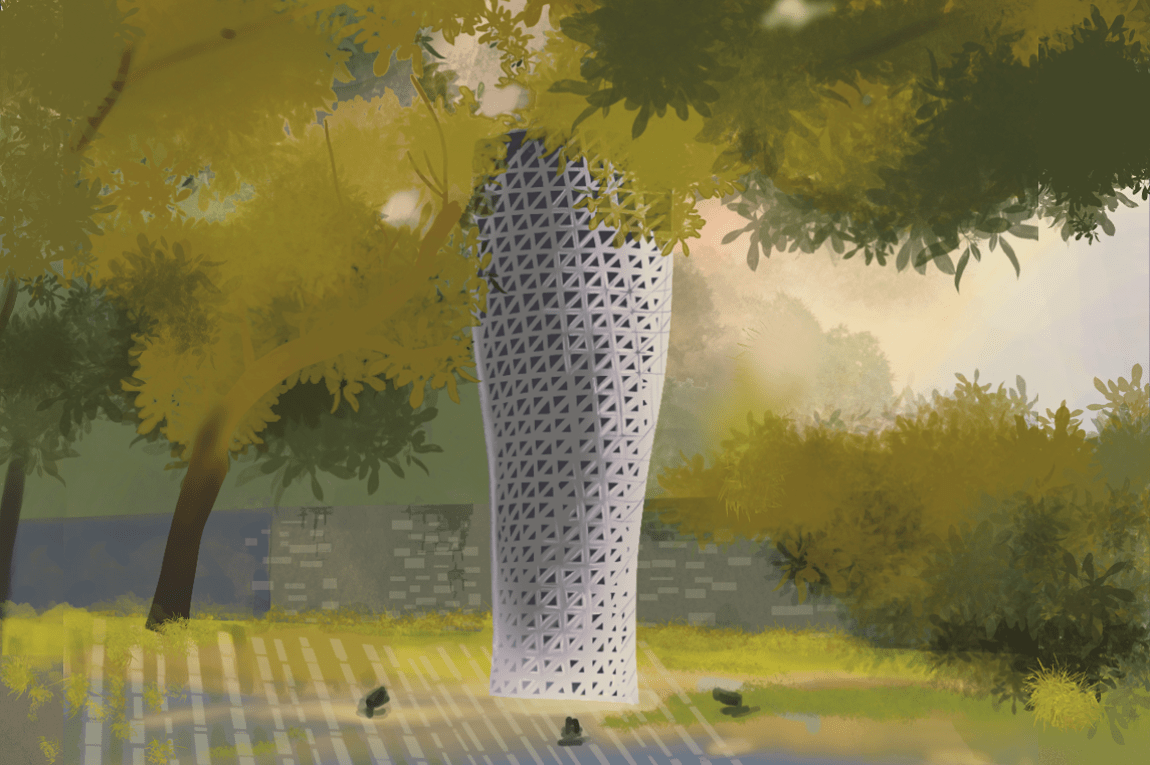

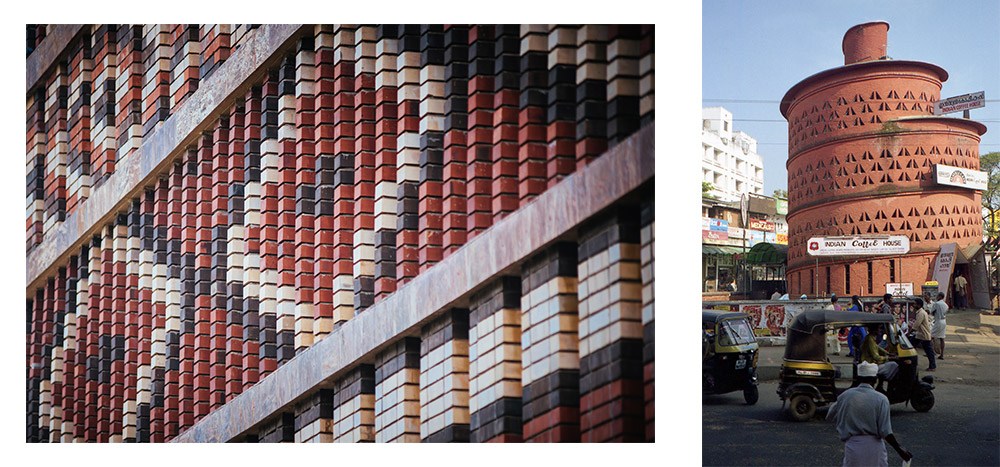

No conversation on the jaali is complete without a hat tip to British-born, Gandhian architect Laurie Baker whose contextual designs — like the Centre for Development Studies and the Indian Coffee House (Maveli Cafe) in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala — shaped post-independence aesthetic sensibilities. “Baker’s work with bricks has been vital in asserting the adaptability of the material… His brick jaalis are a fundamental interpretation of the vernacular vocabulary that we continue building upon to this day,” says Sairam.

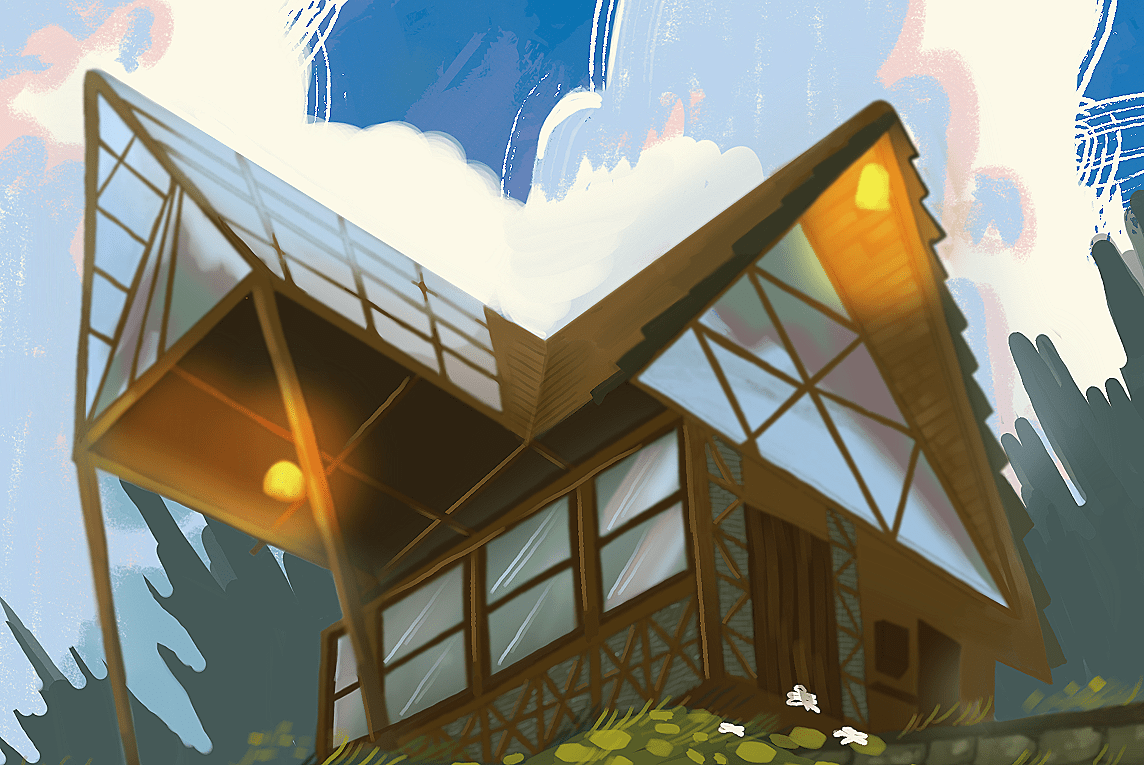

In recent times, the jaali has repeatedly proven its versatility: At boutique hotel RAAS, Jodhpur by Studio Lotus, it appears in locally sourced and handcrafted red sandstone. Terracotta latticework forms the skin of the kindergarten block at DPS, Bangalore, by Khosla Associates. And a design rendering of the Punjab Kesari Headquarters in New Delhi (which is slated to open later this year) by Studio Symbiosis Architects, sees a precision-cut, glass-reinforced concrete facade whose pattern shifts in response to the site.

Beyond the Built Form

This architectural element has played muse to many a creative discipline. Of note, is its contribution to textile design. In Nur Jahan, author Ellison Banks Findly says that the Mughal empress patronized all the arts, from architecture to textiles; marrying aesthetics and techniques from Islamic and Hindu traditions. Chikankari embroidery and its definitive jaali threadwork is said to be inspired by her. In Embroidering Lives, author Clare M Wilkinson-Weber mentions local stories that say the queen’s love of Persia’s stone tracery led her to get the designs replicated on her clothing. Perhaps, this is the link between the Arab mashrabiya — a type of latticed, wooden window — and the jaali.

With fabrics, Benarasi cutwork, block prints and ikat have become part of our personal spaces. All of these bear connections to the design principles of the jaali. Khosla explains that the precision of the geometry makes it simple for a weaver to construct a basic grid, which can be further populated with more geometry or stylized motifs. Kiwach, for instance, one of Freedom Tree’s longest running prints, creates a geometric surface progression with the hexagonal form of the betel nut. Designs by Krsnaa Mehta, Founder and Design Director of India Circus, often draw on Mughal aesthetics — the brand’s wallpapers, Curtains of Versatility and Timid Royalty, feature the jaali. Then there’s interior designer Marie Christine Dorner’s opaline Jali table lamp for French furniture company Ligne Roset. The jaali as a frame is another commonplace idea that goes back to the delicate borders of Mughal miniatures. In a more glamourous avatar, it dazzles with gems and semi-precious stones in the portfolios of jewellery labels like Tribe by Amrapali and designers like Viren Bhagat.

Much like its design ideology, the possibilities of this iconic motif are infinite. As Khosla concludes, “The whole universe expands when you see how you can make the jaali absolutely stunning for people to look at on an everyday basis.”

Gretchen Ferrao Walker is an editorial consultant who has collaborated with Indian and international publications like GQ India, Forbes India, Time Out, Architectural Digest India, Design Anthology and Collectively.org. She is the former editor of travel bimonthly Time Out Explorer and current mum to a 2-year-old. She enjoys embroidering and making pictures.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.