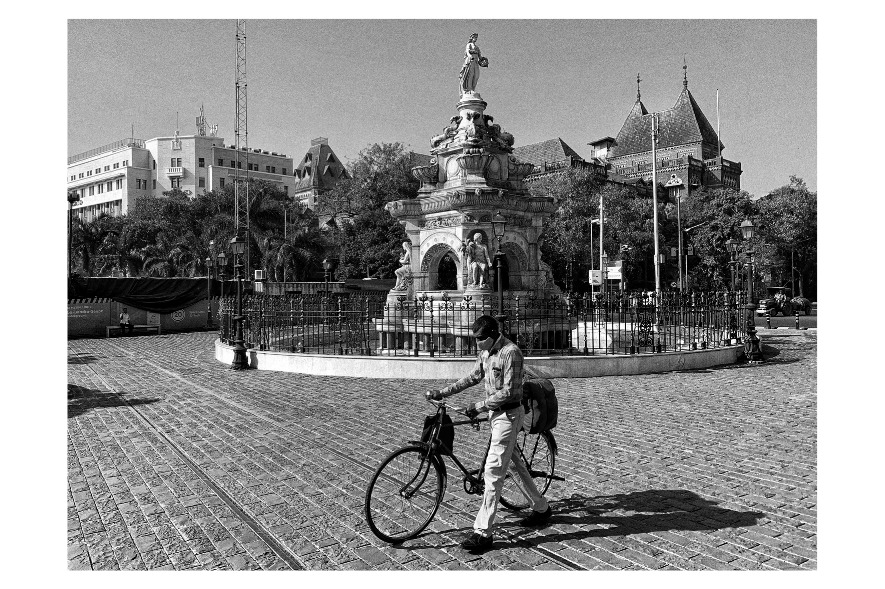

For many of us, cycles are our first memory of being completely independent. It’s in that moment when you’ve been peddling for a few minutes and turn back to find out no one’s holding on behind you — you’re doing it all on your own! — that you realise how completely self-reliant you can be.The pandemic has left many of us feeling scared and anxious, stripped of our agency, unable to control things around us. It is no surprise then, that so many around the country have turned to cycles this year. In fact, bicycle sales in India grew more than twofold between May and September 2020. City corporations across the country have also been encouraging — there have been guided cycle tours, new infrastructure proposals, and developments that make it easier to stick to two wheels. Some have turned to cycles for the freedom they offer, and some have turned to them out of necessity.As Mumbai opened up after months under lockdown, I stepped out in my neighbourhood to spot cycles doubling up as vehicles of agency and joy. Here, we track cyclists through the course of a day.

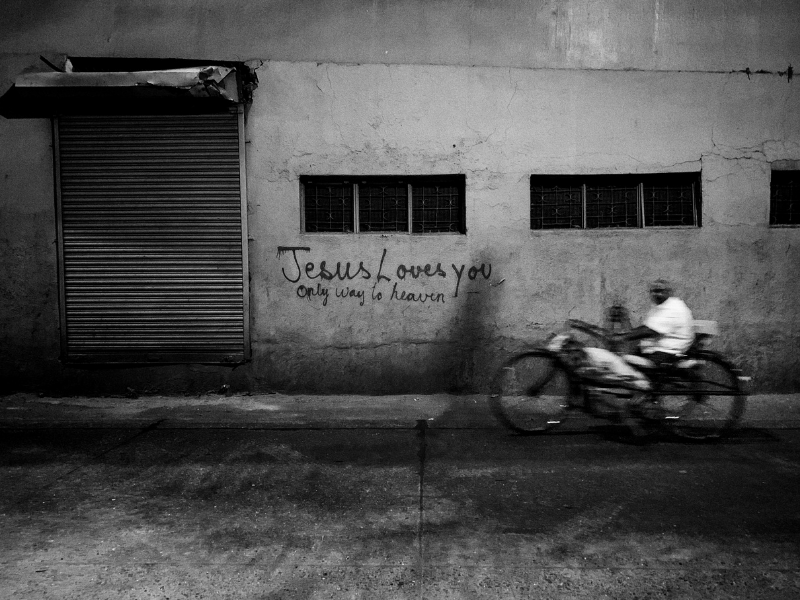

It’s 5.15 am on a Saturday morning, and Anthony Dcosta, 31, is in his home in Charkop, Kandivali, prepping for an off-road biking trip. He packs a puncture repair kit, some food and a spare tyre and heads out to the Gorai jetty by 5.40 am. Dcosta, who works as a customer service trainer for an e-commerce company by day, is a mountain biker on weekends. This, he explains, basically involves riding on unpaved roads and forest trails in and around the city. He takes the first ferry out to get to Gorai by 6.10 am, where he officially starts his ride. While Dcosta’s been cycling for as long as he can remember, he only got into mountain biking five years ago. He cycles up a hill called Manori Rockface, wedged between Manori and Gorai. The trail is beautiful, and once he’s up, he takes a break, eating a protein bar while watching the sun rise over the sea. Then he starts his ride back. “When the lockdown started, it was difficult to access [most] places, so I started mapping the whole city for places where I could cycle,” he says. “Basically, I tried to map all the locations around me in a 12km radius.” If not the Manori–Gorai stretch, Dcosta usually goes to Aarey Milk Colony or Uttan, also a short ferry ride away.

As Dcosta returns home at 9 am, in another part of the city, Nilesh Shersingh Vishwakarma heads out on his cycle. Vishwakarma, 28, works as a watchman in a housing society in Borivali’s sleepy, green IC Colony. With the onset of the pandemic, the building’s residents, most of them senior citizens, have relied almost completely on Vishwakarma, who also lives in the society, to be their bridge to the outside world. He has just washed the neighbourhood cars and is now heading out to buy milk for two families in the building. This is just the first of many such trips he takes throughout the day on his trusty old cycle.Vishwakarma came to the city from Nepal eight years ago, and has worked in this society for six of those years. He only learnt to cycle when he got here. “My village in Nepal was on a mountain and almost no one owned a cycle,” he explains. “Here, it is a necessity.” His cycle has been a boon for him and the residents of the building, especially in the earlier phases of the lockdown. It’s what kept everyone’s pantries stocked. He returns from his errand almost immediately, in tow with the milk and a fizzy drink to share with his three-year-old as the day gets hotter. Then he’s off in the other direction to buy potatoes.

At 10.30 am, another gentleman in Borivali heads to the station. 53-year-old Haresh Gala boards the local train, which is a little less crowded nowadays. As he stands at the edge apprehensively, he thinks of riding his cycle to work again. For the first few months of the lockdown, Gala rode his son’s cycle to his garment business in Goregaon. “There was no public transport, and I had to be there to oversee everything, so I decided to just start cycling to work,” he says. It would take him about an hour to reach, but he enjoyed every minute — he hadn’t been on a cycle since he was 14 and he was happy to find out he still had it. Train services in the city have been partially restored now, so he doesn’t need to cycle, but he still occasionally sets out with a gusto that puts the rest of us to shame.The afternoon is hot and dusty, and almost everyone retreats indoors, except for Vishwakarma and his son, who lounge under a shady gulmohar tree outside the building, dreamily chatting about motorbikes.

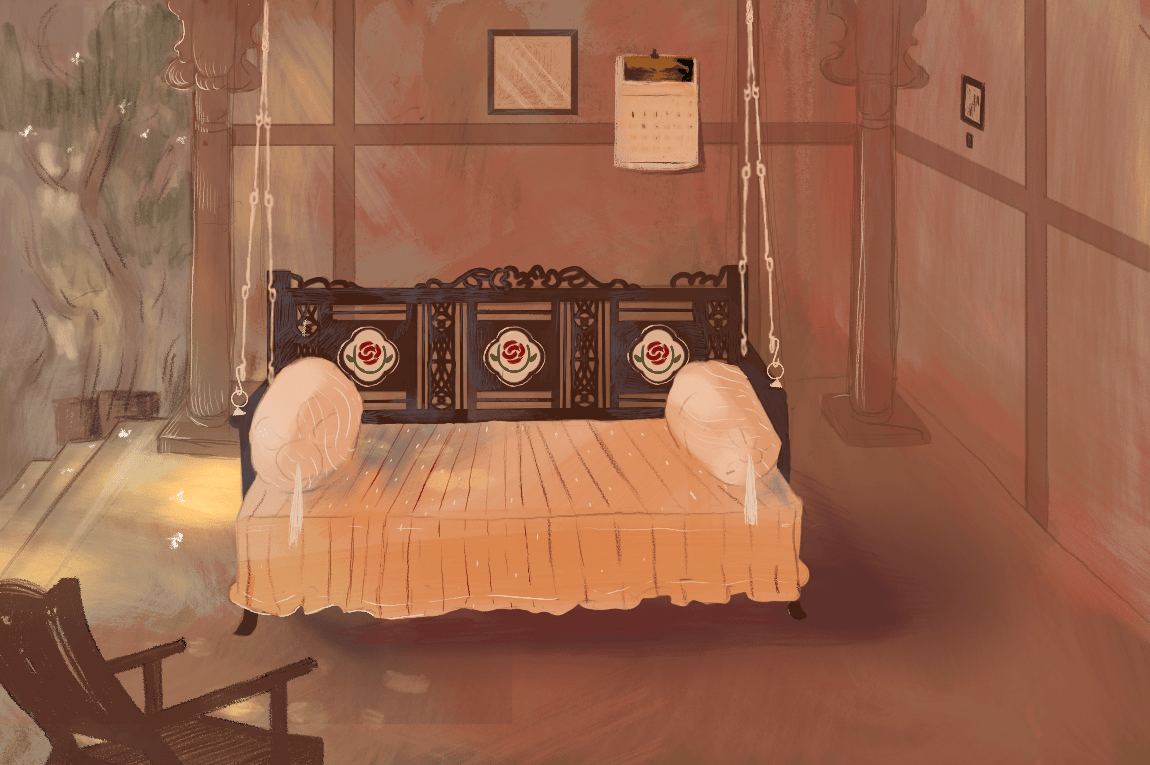

At dusk, another resident from Vishwakarma’s building heads out, hugging the shadows. Rina Jani, 55 — my mother — is learning how to cycle. “This has been a dream since childhood,” she says. “I’ve seen my brothers and neighbours learning how to ride, but I wasn’t allowed.” The lockdown, with its restrictions on movement and lack of public transport, made her feel completely dependent on others and this pushed her to finally learn. “There were a few things holding me back — my age, my weight, what will people say when they see me?” While she’s slowly trying to overcome these obstacles as she practices on a rented bicycle, sometimes with her family watching over and yelling instructions, she still prefers to come out after dark around 7 pm, “when no one’s looking”. She practices for half an hour in the street outside the building, luckily devoid of traffic at all times. “It’s very freeing. You are on your own, not depending on anybody. I like that.”Just an hour later, 22-year-old Aaron Barboza, wraps up his work for the day and goes out to cycle around his Santacruz neighbourhood. Barboza, who works as a consultant for a multinational accounting organisation and runs a food service start-up on the side, has been cycling since childhood. He stopped a few years back when his bicycle was stolen. However, during the lockdown, he purchased a new one as soon as the nearest cycle shop opened up. “The cycle for me was sort of an excuse to get out of the house while being safe and socially distanced at the same time,” he says. Heading out at 8.30 pm with a bottle of room-temperature water infused with green tea, he cycles to Juhu beach, where he stops to take in the breeze and sip on his water, before turning back. “This lockdown period has been great for my mental health,” he says, and he even hopes to be able to bike to work in the future.

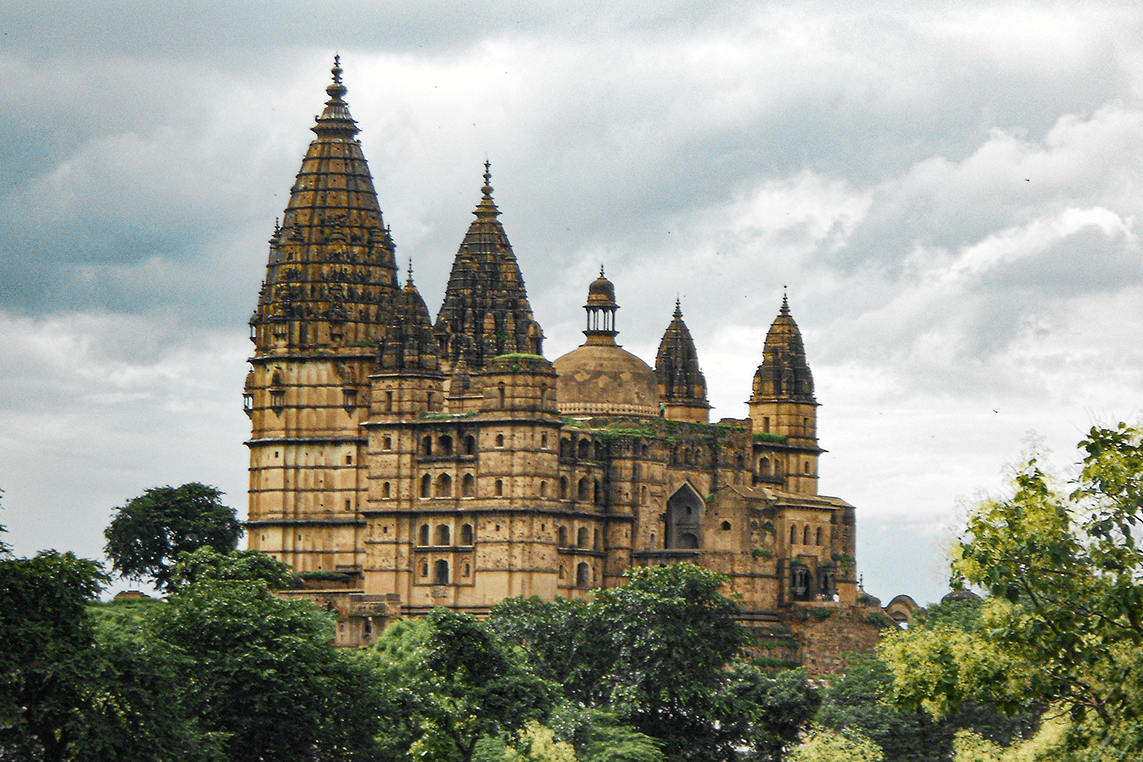

It is now 12.30 am. On a night that is eerily quiet for the city that never sleeps, Mulchand Pal wheels out his cycle to a discreet spot at the corner of a street in Borivali. Laden with a large kettle of hot milk, sachets of powdered tea, coffee and Boost, and cigarettes, this cycle wallah is open for business. Pal, 45, has just returned to the city from his hometown near Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, and business has been slow. He was among the worst hit during the lockdown, with no business and no jobs at hand. He first moved to the city when he was 15, and has worked as a daily wage labourer or by doing odd jobs. He started selling cigarettes and tea on his cycle after other shops shut down about two years ago when a former boss suggested it. It has been a good source of additional income — in the day, 3pm onwards, he works at a hotel as part of the housekeeping staff. As soon as his shift is over at 12 am, he goes home to boil milk, prepare his cycle and head to his spot, keeping a keen eye out for cops. He stays there till 4 am, catering to a smattering of customers, and then heads home to rest before doing it all again.

Jessica Jani is Associate Editor at Paper Planes. She’s on Twitter at @_jesthetic.

Zahra Amiruddin is a writer, photographer, and educator based in Bombay. When she’s not chasing after pockets full of light, she practices conjuring a patronus in her free time. She’s on Instagram at @zahra.amiruddin.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.