Shahnaz Habib’s debut translation — of Benyamin’s novel Jasmine Days — won the JCB Prize for Literature in its inaugural edition (2018). The New York-based writer and translator tells us about a childhood delightfully abound with books, the thrill of reading poetry in multiple translations, and why it helps to be a complete stranger to a draft during the editing process.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

At the moment I am reading Dina Nayeri’s The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You — a beautiful book that challenges the standard narrative about migration. I frequently return to A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith. This is a childhood favourite, a book I read long before I knew of a place called Brooklyn.

‘Jasmine Days’ by Benyamin is the first book you’ve worked on as a literary translator, describing it a “translation of a (fictional) translation,” followed by its twin novel ‘Al-Arabian Novel Factory’. What made you decide to take up the translation of these two books?

I think of Benyamin as a writer who captures the way migration is an essential experience of our time, especially for Malayalis. As a Malayali migrant myself, maybe I was trying to understand my own experience. I also loved the title Al-Arabian Novel Factory. We all live inside novel factories and when I read the book, with its mischievous meta glance at the business of writing, I knew I would enjoy translating it.

Oftentimes a book might be tremendously rooted in a certain culture, ethos, social norms and mores or geography. How do you retain the integrity, readability, or even the musicality and cadence of the work while translating it? Is there a sort of confirmation bias or inadvertent manipulation that might creep in while doing so?

I am sure my translation involves inadvertent manipulation and confirmation bias because pretty much every human interaction involves these things. Sorry for this dim view of our world! I find it helpful to keep in mind that it is impossible to fully “retain” the book that I am translating. Translation involves some shapeshifting, so the question is within the framework of that shapeshifting — how do you convey what makes this book interesting or important? Readability and integrity may often be in conflict with each other, so then it comes down to choosing the proportions for each element. Musicality is especially hard to recapture when you are going from one language to another, and if you try too hard, it can seem almost like a parody. But while all of this can make translation seem such an uphill task, I find that translation itself works to create a layer of ambiguity and subtlety for a text — these are both qualities inherent in good literature.

What memories do you have of reading as a child? Did you grow up reading — or perhaps hearing or overhearing — different languages?

[I have] lots of memories of reading. Walking into the Ernakulam Public Library so many times a week that the librarians were concerned. Book fairs at the Town Hall. Stealing a book from our local bookstore and getting caught red-handed. My parents were definitely the kind who preferred to spend money on books as opposed to painting the house or buying new clothes. I also had wonderful Malayalam teachers in school as well as in college. They showed me how playful and subversive Malayalam could be, how it was the language of court jesters and revolutionaries. I also learned some Arabic in the madrassa I attended after school, Hindi from the television. So looking back, it seems to me, a childhood full of sounds and words in different languages.

While writing, do you leave room to let yourself explore and follow things that perhaps may not materialise or turn into well-defined projects?

Yes, definitely. It’s part of practising the craft, keeping the writing muscle strong. And sometimes, the “unproductive writing” might lead to ideas or stories that eventually become projects. If I am stuck for ideas, I frequently look through my journal and scavenge. And when I am reading in Malayalam, I find myself trying out English translations of phrases and words in my head — can’t turn it off.

How do you edit your own work? Is it important for you to disrupt your writing routine in any way?

If I had a writing routine to disrupt, I would be thrilled. My current struggle is to put in place some semblance of a writing routine. I was traveling all summer and despite my good intentions, I did not write much. Ideally I’d like to write a little every day. So that’s what I am working towards. As for editing, what really helps me is putting lots of time between drafts. It’s not always possible on deadline, but it helps so much to become a complete stranger to the draft.

To what degree does the author of the original work influence you? Is the process of translation a collaborative exchange of ideas or is it more of a one-woman show?

I’m not such a seasoned translator that I can give a definitive answer to this one. I believe it depends on the book. I did not interact with Benyamin very much during the translation process and I did not find it necessary. But he and I were just talking of one of his other books which is much more rooted in local lore and slang, and if I were to translate that, I think it would be much more collaborative. So it would depend on the book in the end. But regardless of whether I’m in touch with the author during the translation process, his or her influence is constant. The book is their book and translating their words means a constant interaction with the mind and values and craft of the author.

At times publishers peg a book as “the definitive translation.” There is never a single way to translate a book; there might be several styles of translating something. How does the reader then know which one to read?

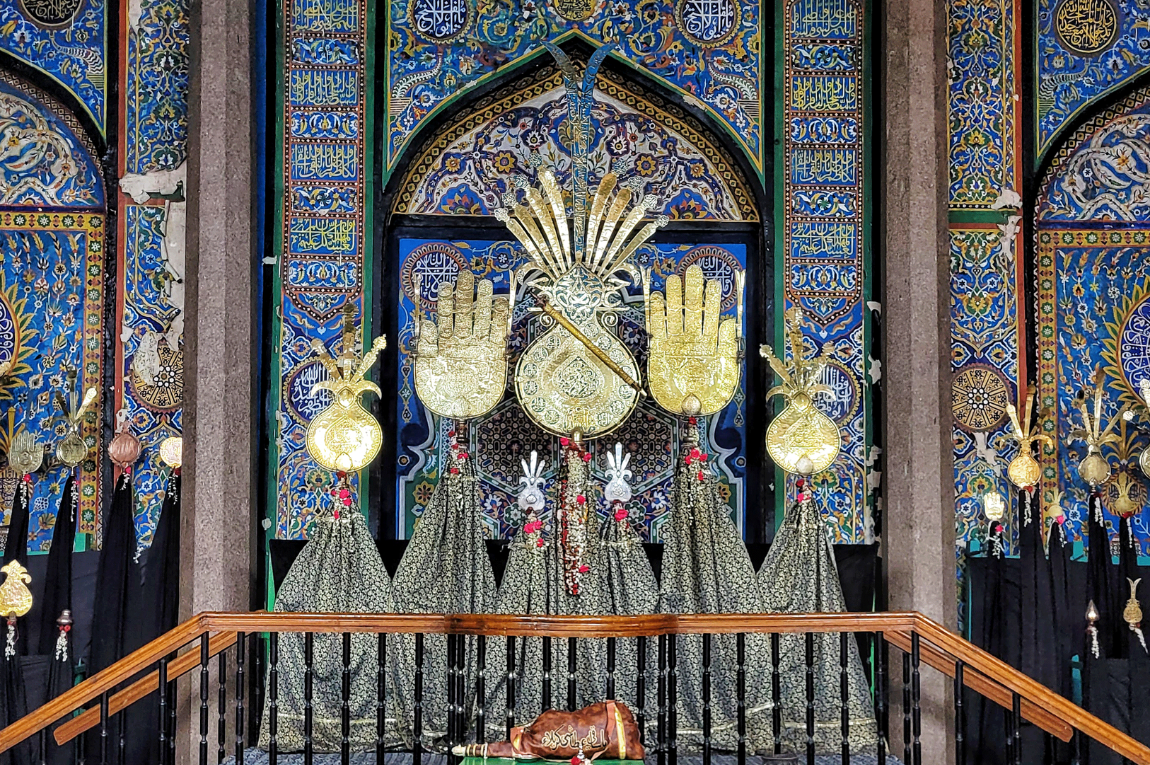

Yes, each translation is a subjective version of the book. It is up to each reader to find the subjectivity that appeals to them the most. I have several translations of the Qur’an, and I love reading The Sublime Qur’an by Laleh Bakhtiar who has paid deep attention to how male scholars have interpreted the etymology of Arabic words. Her translation rectifies some of these twists, which is a project I am invested in — how everyday words privilege men and male points of view, and what we can do to neuter that.

I think it is also particularly rewarding to read poetry in multiple translations. Do you know the book, Into English [edited by Martha Collins and Kevin Prufer]? It’s a collection of various poems, each with three different translations side by side. I adore and celebrate this kind of multiplicity and the fact that there can be no one definitive rendering.

How do you think more support can be garnered in India for encouraging translation across genres?

So many answers here, but to highlight just one strategy — I wish there were more grants for translation projects. Prizes are wonderful, but a prize is given to a finished, published translation project. Grants would help translators take chances on work that might not be commercially successful. Also, many regional languages such as Malayalam have rich literary criticism and non-fiction traditions. Most of what gets translated is fiction, and I would love to see more non-fiction in translation.

Do you have a list of works you wish you could translate, language no bar?

I grew up reading Soviet children’s books because of the connections between our governments. I have often thought how wonderful it would be to read them in the original languages — in Russian, Kazakh, Uzbeki, and so forth. The ones I read were beautifully translated into English, so it would be quite redundant but yet a rich experience for me personally to translate them.

If you had the chance to create a lexicon of your own, what would you come up with?

I would come up with a pronoun for God that goes beyond ‘He’ or ‘She’.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)