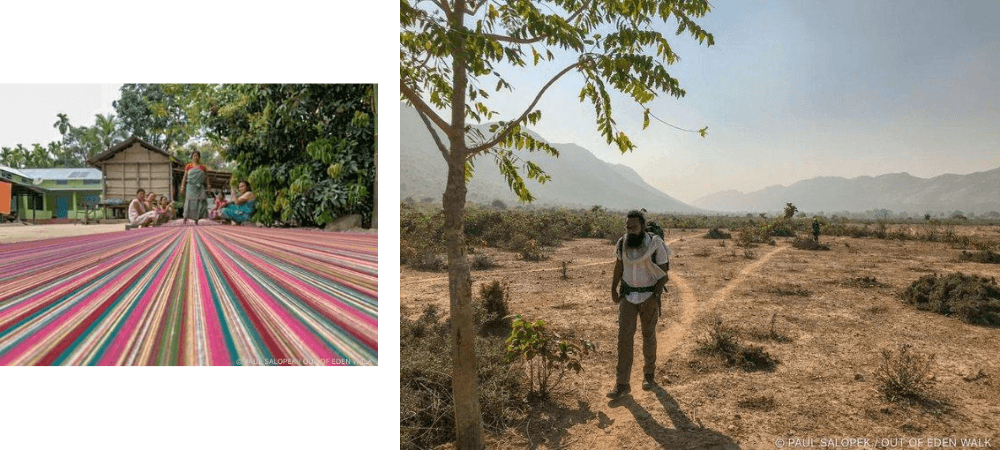

Writer and National Geographic Fellow Paul Salopek has largely lived an itinerant life. Currently in northern Myanmar, the two-time Pulitzer Prize–winning American journalist is walking the earliest routes of human migrations, reporting and documenting humanity’s shared histories as well as the turmoil of the present. Conceived in 2013, the walking journey began in Ethiopia and will conclude in Tierra del Fuego, the tip of South America. Spanning four continents and encompassing a multitude of narratives from climate change to the history of headhunting, Salopek’s journey so far has been unpredictable, revelatory, uplifting and awe-inspiring. While traversing through India last year, Salopek and his walking partners and fellow contributing journalists encountered grave ecological issues surrounding the country’s looming water crisis, and the threats they pose to riverine communities. Here, Salopek tells us why borders can go unnoticed, how poetry enables him to understand a landscape, and why by slowing down you actually “break” news.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I’m reading Zadie Smith’s Intimations; Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary; Peter Hessler’s River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze; and Thant Myint-U’s The River of Lost Footsteps: Histories of Burma, in addition to several scientific papers about plant diversity in northern Myanmar.

I re-read a lot of writers — Barry Lopez, Ryszard Kapuscinski, Annie Dillard, Cormac McCarthy, Pattiann Rogers, Denis Johnson, Mary Oliver, Juan Rulfo and so many others.

The Out of Eden Walk is a 21,000-mile transcontinental journey on foot, to retrace the footsteps of humankind’s first migration out of Africa about 50,000 years ago. Could you take us back to what sparked this idea? Have geopolitically defined borders altered the way you first envisaged your walk?

It came to mind as a way to braid together all the different “genres” of contemporary literary reporting that I’ve been doing for years: a continuum of one unified, linear narrative. It was a quest story that touches upon science, culture, economics, health, war, and every other kind of story under the sun and moon. I was looking for a meta-narrative that links it all together — one that transcends the little boxes that journalism puts life’s complex, overlapping stories into, one that belongs to everyone. A long walk in the pathways of the common ancestors, fits the bill. I’ve been very fortunate in finding institutional partners, like the National Geographic Society, who have stuck with me over the years.

What transformation does your work undergo upon crossing borders? Are all borders “in-between” spaces, so to speak? How drastically does the arc of your storytelling change with crossing borders?

Borders can act as chapter divisions or not be noticeable at all. The border of the Caspian Sea — dividing a “European” Caucasus and an “Asian” Central Asia is a significant cultural and bio-geographical border. The old colonial line between the steppes of Mangystau in Kazakhstan and the steppes of Karakalpakstan in Uzbekistan separate nothing meaningful, really — you may as well say that you’re dividing the wind. So it varies. Not all borders are equal.

You’ve also parallely made a map documenting “police stops”, or all the times you were questioned by local police. How do you deal with the situation if it turns particularly hostile?

The police-stop map is just one of many that my cartographer-partners at the Harvard Center for Geographic Analysis and Esri [Environmental Systems Research Institute] have built from the walk. I suppose I deal with security forces the same way anyone does. I’m polite and respectful, and hope the officers will reciprocate. Most of the time, they do. But there have been some tense encounters. I’m acutely aware that my identity — a white guy — usually means I get special treatment. The flip side is it can also bring unwanted scrutiny. I’ve been detained a few times and expelled once.

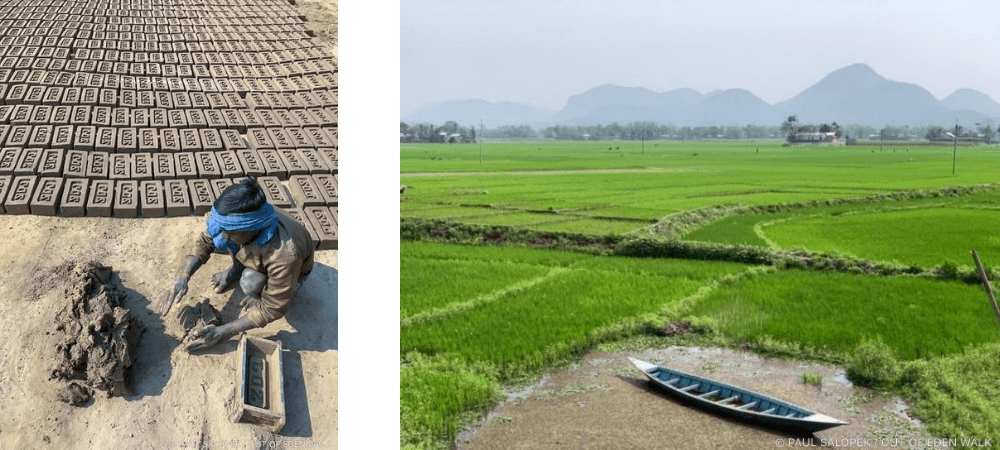

A large part of your 17-month-long journey in India throws light upon riverine ecologies and an impending water crisis in the country, owing to the desecration of our lands and waters. What were some of the grave concerns among the riparian communities you came across?

Everything you might imagine. Absence of water due to agricultural over-pumping or climate change, the poisoning of water due to human or mineralogical contamination, the destructive power of rivers that is often aggravated by poorly conceived management plans, like thousands of dams and dikes. As my walking partner Arati Kumar-Rao says, rivers aren’t pipes, but humans often treat them that way.

You spend most of your time out on the road, traversing a range of landscapes and environments. Has this prompted you to seek out the works of certain writers, as a way to perhaps better understand the experiences you were going through?

I try to read the work of writers, poets, journalists and scientists who inhabit the landscapes I walk through — they’re the real experts. I’ve found that poetry offers a good foundation. In the Rift Valley of Ethiopia, it was the songs of the Afar camel pastoralists I walked with. In the Caucasus, they revere their national poets the way other societies lionise their generals or politicians. In Kyrgyzstan, the national epic poem is half a million lines long — an encyclopaedia of local character and psychology. And of course, India overflows with poets, both world-renowned and obscure.

On the other hand, have there been instances when the experience or encounter you had was so invaluable or overwhelming, that even language seemed inefficacious?

This is most of the time.

How do you go about selecting your walking partners or interpreters/guides on every stretch of your journey?

I think I’d call it mutual selection. People seek me out as much I cast about for victims. I mean, it takes a fairly unusual person to cast aside their normal life and go walking for weeks or months. Whatever the individual case, the end result is the same. These are not guides; they’re co-owners of the journey and its stories. They generate their own narratives, from the invaluable perspective of rediscovering “home”. The nuances they can bring to this experience are therefore often a thousand times more insightful than mine. We publish their work, and more important, they become family.

When compared to the present state of the media and the way we consume the news, your approach of telling stories is slow and immersive, almost like picking up the pieces after the dust has settled, advocating for being mindful of one’s immediate surroundings. How do you maintain a consistent flow between your stories, given the larger narrative?

I’d argue that what the walk’s approach does is more than just a “slow journalism” ramble through current events after they’re covered as “fast news.” By slowing down, you actually break news, because you see stories that are missed by other writers who speed past them obliviously. I’ve broken stories on the effect of Somali piracy on farming outputs in India (it’s complicated), gotten unique access to Israeli settlements in Palestine by approaching the topic on foot (it’s somehow not as threatening), and literally tripped over amazing megaliths in Central Asia that were largely unknown to the scientific community.

Your acquaintance with the land is as a chronicler, a walker, a reader, a listener. Do you see yourself as a catalyser of something much larger?

I’m not an activist. I’m a very, very slow storyteller. If others find some of these ideas and approaches worthy of a look, some investigation, and maybe even adoption — great!

Given the present circumstances due to the global pandemic, what shape does the walk now take? Are you looking at it as a pause to ponder and reflect? Where do you go next from northern Myanmar?

Pauses are part of any journey. As terrible as the pandemic is, it’s part of life’s mosaic, and I’ll adapt to it the way everyone else is. I’m working on a book during my wait for borders to reopen in Southeast Asia and China.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)