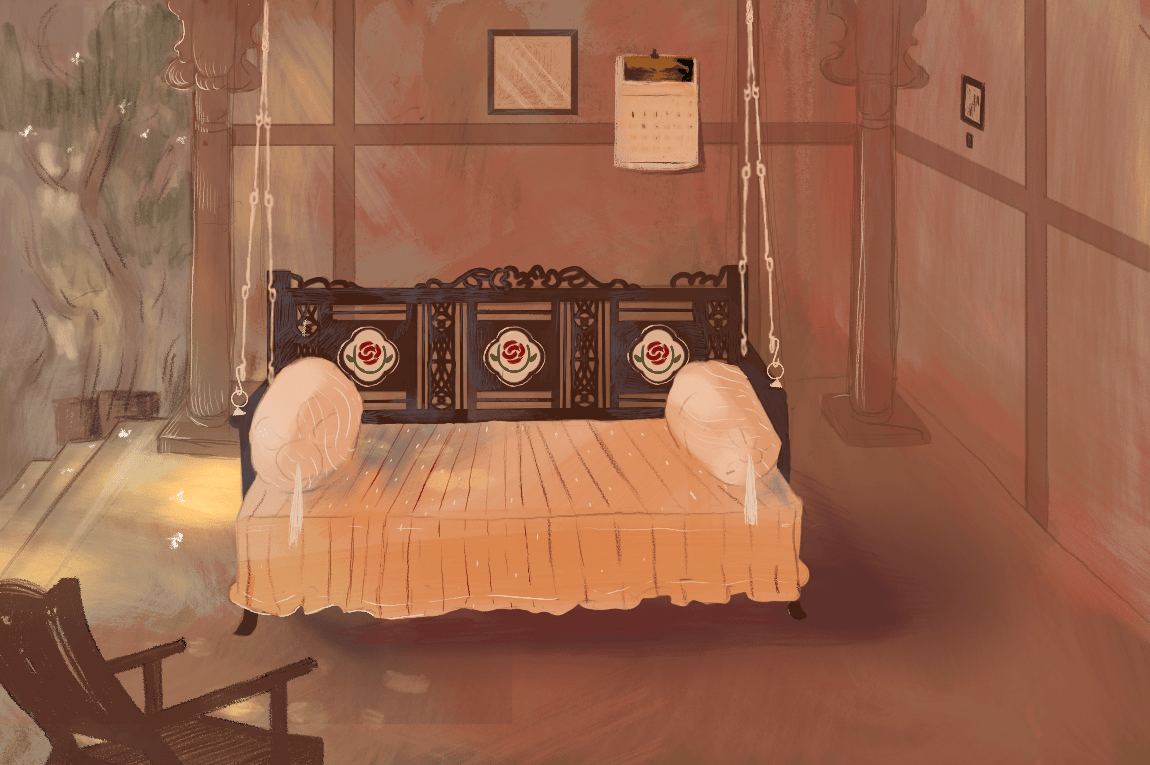

Growing up, I spent all my summers in Sanjan, a little Parsi town along the coast of Gujarat. Our drive through the village would take us through lanes of dilapidated, abandoned mansions, with forests growing in them, and end at a sunny colonial guesthouse. It was little known to tourists, lapped in nature and I spent many afternoons sunning myself in the verandah and playing cards on the giant four-poster bed. A few years ago however, to cater to an influx of tourists, the owners pulled down that guesthouse and now, there’s a two-storied apartment complex with air conditioning in its place.

It’s tempting to romanticise buildings of the past, to hold them as testaments to a glorious history and keep them at a distance, like sanitized museums of memory. But heritage is not about the “good old days”, it’s about the identity it manifests today.

In April 2020, the UNESCO-listed Basilica of Bom Jesus in Old Goa suffered damage and flooding due to unforeseen rains. The structure has been in a state of disrepair for several years now, and repairs initiated by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) began in January 2020. With the COVID-19 lockdown, however, the work stopped, leaving the structure exposed to the elements. The basilica houses the remains of St. Francis Xavier — thousands congregate for his feast each December. It is arguably one of the most important heritage sites in Goa. The damage caused by the rains finally shone a light on its neglect, sparking local outrage. Repair work was re-started by the ASI in late April.

Goa-based architect Lester Silveira has been actively involved in raising awareness for Goan heritage structures. Along with a few other architects and well-wishers, he has been visiting the basilica to advise the rector on its future restoration. “The rains damaged a part of the basilica which was already weak to begin with,” he explains. “The immediate solution to that was put in place by the ASI itself. They got a local team and directed them to do the works.” But Silveira, who runs The Balcão, an architecture blog and magazine that serves as an archive for heritage structures in Goa, points out that restoring the Basilica would involve fixing more than just these impending issues — “it’s to do with things at a master planning level, about what kind of systems should be in place to ensure the longevity of the structure.” His goal right now is to bring to light this need for conservation within his architectural circle and among the public. He adds that it’s troubling to think of the state of lesser known heritage buildings in Goa, when the basilica, which is such a renowned structure, is so neglected.

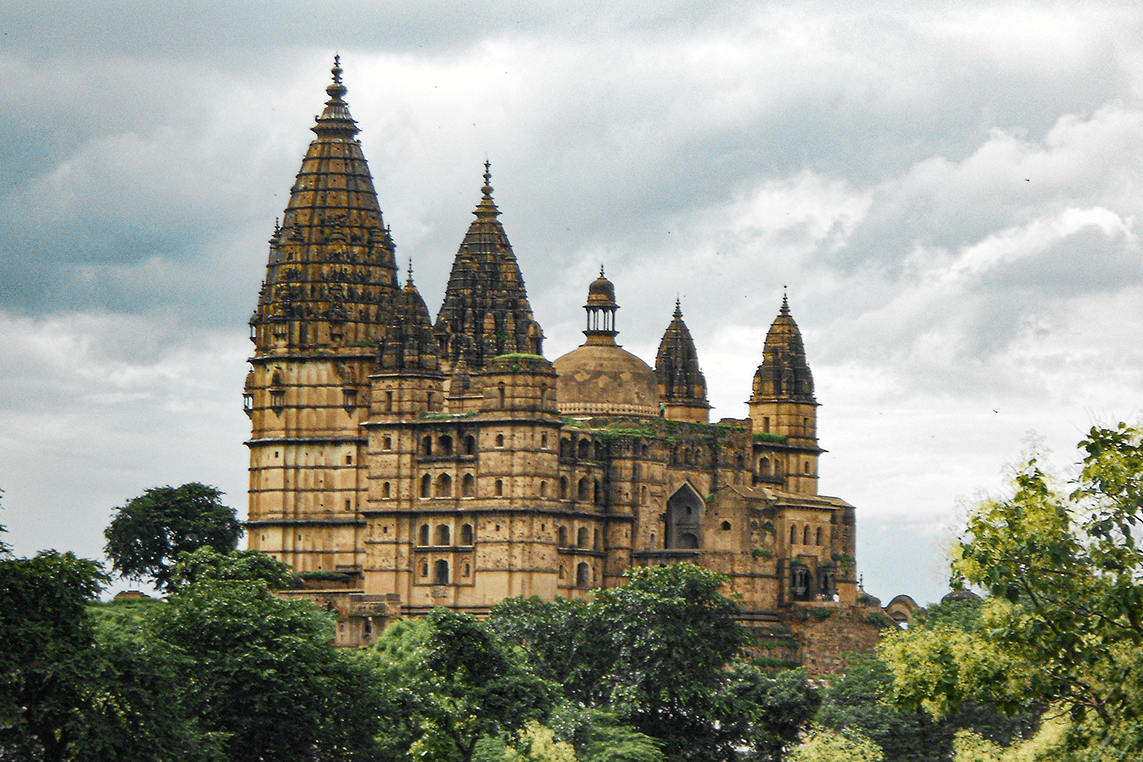

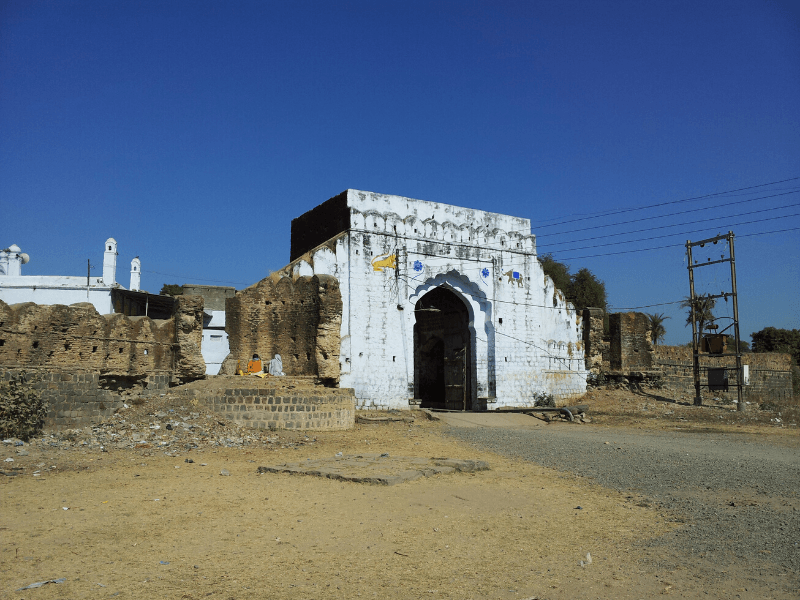

According to Silveira — who is also part of the newly-formed Goa Collective, which is working towards better public and urban spaces in the state — these spaces represent a physical identity of a particular culture. Award-winning conservation architect Aishwarya Tipnis, who has worked closely with UNESCO on the conservation plan for Bandra station, Mumbai, and the Darjeeling Himalayan railway in West Bengal, echoes a similar point. “Heritage helps reinforce identity,” she says as she cites one of her projects — the Mahidpur Fort in Madhya Pradesh. About a hundred families live inside the massive fort, she explains, and the state government had sanctioned a crore for its restoration. Since their budget was limited, Tipnis and her team decided to restore only the front gateway and the walls and bastions of the fort, as these were the structures that would most benefit the families inhabiting the fort. “I think the best feedback I got was when we were wrapping up the project, and one of the gentlemen from the village came and thanked me for restoring it,” says Tipnis. “I was a little shocked and I said, ‘Why are you thanking me?’ He said, ‘You know, there was a wedding in our village and the baraat came through this newly restored grand gateway and all of us were very proud to welcome them.’” For Tipnis, this sense of cultural identity — of the man, of his neighbours, of his village — is what was restored, along with just the fort walls. Besides, as she points out, it is always so much more sustainable to restore than to demolish a structure and build it from scratch.

Acclaimed conservation architect Vikas Dilawari, who has worked on restoring buildings like the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum, Esplanade House, and the Royal Bombay Yacht Club in Mumbai, suggests that the neglect these structures face stems from apathy. “We have so much abundant heritage, so much wealth in terms of cultural heritage, that we take it for granted, we don’t respect it,” he says. “None of the governments are keen on genuine overall conservation of [the] built environment. Seventy years down the line, we don’t have a conservation ministry, we don’t have proactive involvement in declaring something, protecting it and encouraging it.”

But what can we, as individuals, do? According to Tipnis, there is a role for everybody in conservation. Movements created by people who care about a space they are connected to can result in real change. Take, for example, Tipnis’ efforts over the last decade to put the former French colony of Chandernagore (Chandannagar, in West Bengal) back on the map. The town houses Indo-French architecture that is a unique amalgamation of European and Bengali aesthetics, and was in a state of utter decay. Tipnis and her team started a citizen’s initiative, where young students from and around the town pitched in and collected stories and oral histories about its heritage. They created a digital website too, where “a lot of people who had migrated to other places like the USA [from Chandernagore] then got in touch to share their stories. At the end of nine years, the movement had grown enough to push the Government of West Bengal and the Government of France to restore the buildings together. Last year, the governments agreed to restore and revamp the main promenade in Chandernagore. “I think what we have achieved in the Chandernagore project is a process where regular people can bring about change,” says Tipnis.

Similarly, Silveira points to a movement in Chimbel, a town in north Goa, by the Mount Carmel Conservation Association of Chimbel who have rallied to enlist the ruins of the Church and Convent of Mount Carmel in the town as a heritage site. “These [citizens] grew up with this church complex forming the backdrop of their everyday lives. It is ingrained into the cultural and social fabric of the region,” says Silveira. “Thankfully, the monument in Chimbel is on the verge of being enlisted by the Town and Country Planning Department after a long struggle and by the efforts of many stakeholders.”

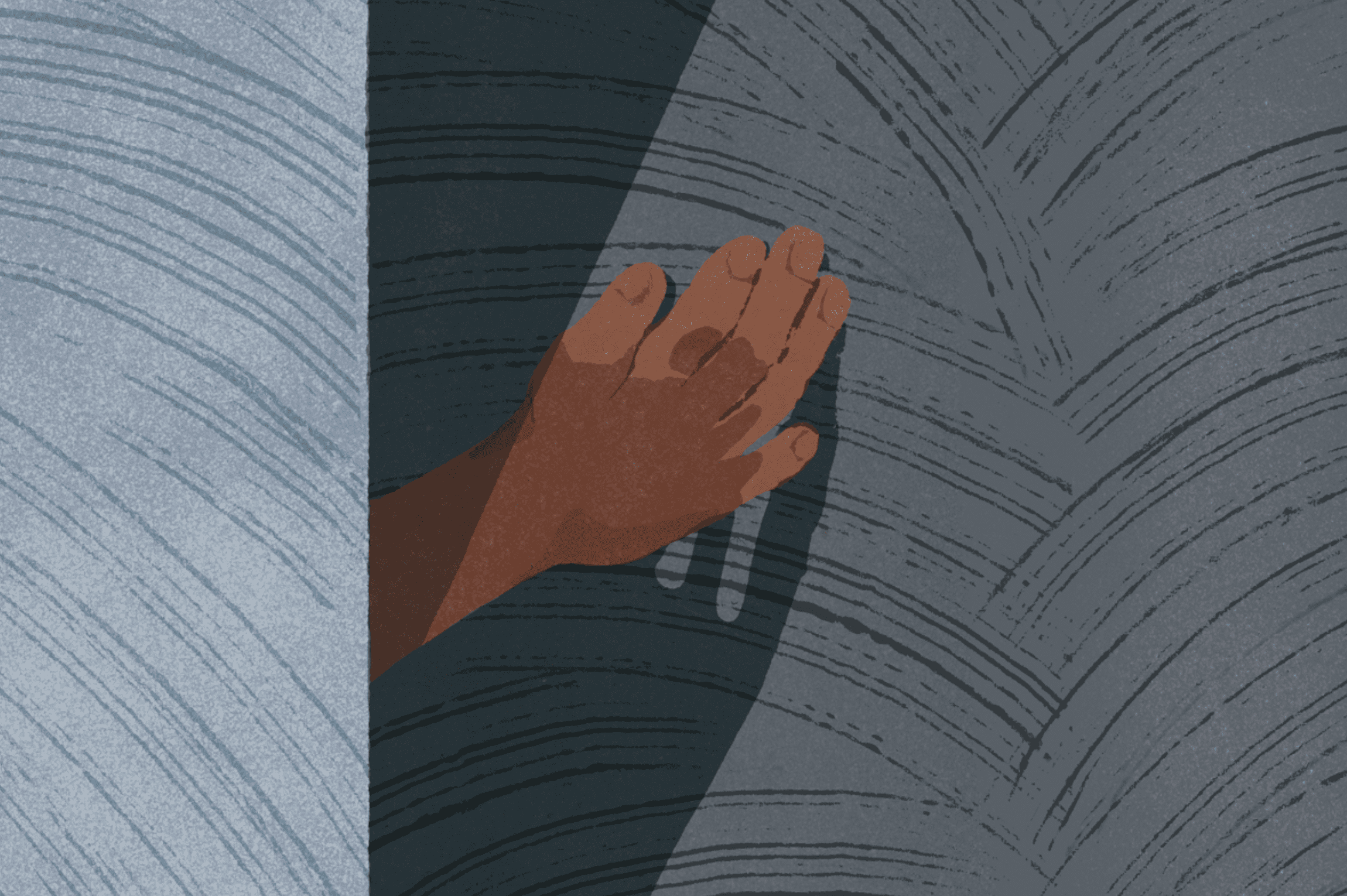

For people to care about a structure, it needs to be relevant to them. Design plays a huge role in making these restored spaces relevant. Dilawari says, “the goal of conservation is to prolong the life of [a structure’s] fabric.” The idea is to remain sensitive to the cultural significance of the space while attempting to make it utilitarian and economical. What is needed most today in conservation architecture is creativity, Tipnis adds. “My philosophy of heritage conservation is to make sure that we are using the buildings that we have, and making changes in them that are sensitive to its heritage, changes that make it relevant,” she says. “Even if you restore a building exactly the way it was built, it is not the same building because the time has changed.”

These heritage spaces are ones in which we live out our lives — they’re churches, old homes, entire towns, and while they are memory markers for many, they’re also living, breathing buildings. We just need to start caring about them, before it’s too late.

Jessica Jani is Associate Editor at Paper Planes. She enjoys reading books, about books, and the scores of magazines she has access to thanks to our amazing library. Find her on Twitter at @_jesthetic.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.