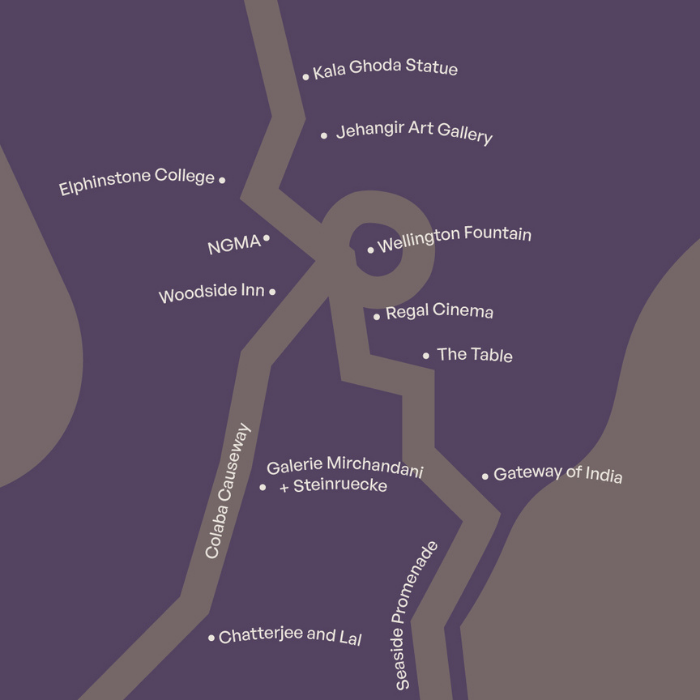

Walking is my preferred mode of transport. Pre-pandemic, I walked daily from my home in Colaba, near the tip of Mumbai’s coastline, to get to Kala Ghoda, the city’s well-known art precinct. Sometimes, it was a little bit closer — to neighbourhood favourites like The Table on Sunday mornings or Woodside Inn for an early drink. During these ambles, it could seem like the legs led the body, tracing a route that had become muscle memory after numerous trips at different times of the day, for varied purposes. There were subconscious calculations made during the journey. Today too, without a thought, I know when it’s a good time to glance at my phone to view a pending notification or when I have to pay attention and look to navigate a familiar puddle that collects yearly with the first monsoon. It seems to me that walkers develop a rhythm as they move through this cityscape.

When I walk from Colaba toward Kala Ghoda, I know instinctively, as I cross the Wellington Fountain, the beautifully restored Gothic Revival structure at the Regal theatre junction, that each step needs my attention. Not anymore on the recently paved concrete footpath outside the National Gallery of Modern Arts. Steps away, as the NGMA ends, it’s like walking back into an older era. The old stone tiles, probably laid when Elphinstone College was built in the 1800s, still persist, complete with their rough surface and even paving. Here, each stride has to be smaller, but it’s heartening to see how the stones have absorbed millions of footprints over almost 200 years. The college, a Victorian neo-Gothic building, has the iconic patterned Minton tiles paving its covered entrance, albeit ones that have been broken and refilled. Still, underfoot they retain the evenness of the tile, leaving the eyes to take in the modern, classic structure of the Jehangir Art Gallery opposite, along with the trees that line the gallery.

On regular walks around Colaba, the pavement is a reminder of what is often missing from so many other parts of the city. For the most part it’s clean, but it is rarely uncluttered. On the main road parallel to Colaba’s seaside promenade, there are street vendors for everything from leather bags to junk jewellery. In the morning, before they open, the sidewalk is littered with tarp-covered boxes, all sealed with a kaleidoscope of ropes.

And then, right by the coast, at the Gateway of India, underfoot for the photographers and the tourists that flock here daily, there is hard stone, cut smaller, smoothened and paved neatly. During the CAA-NCA protests in early 2020, for a night or two, there were slogans being written, samosas being distributed and beds being made on the rough, uneven stone that is over a century old.

The greatest pleasure however, during a stroll through Colaba, comes from bounding up the stairs, sometimes two at a time, to the city’s art galleries. A big cluster of them are sited in the area, in old buildings with wooden staircases. Whether it be Kamal Mansion for Chatterjee & Lal, Queens Mansion for Chemould Prescott Road, or Sunny House for Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke — the sonorous, dusty wooden stairs are resonant, tuned to a frequency that seems to exist only in Bombay, a city that was.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Aatish Nath is an independent writer based out of Bombay. He writes about food, travel and music and enjoys making photographs. His work has appeared in publications such as The Hindu, Condé Nast Traveller India, The Wire, Lost and CityLab, among others. He tweets as @aatishn.

Raj Lalwani is drawn to the familiar and outlandish, and seeks to make photographs that blur the lines between the two. He is on Instagram at @lookdoyousee.