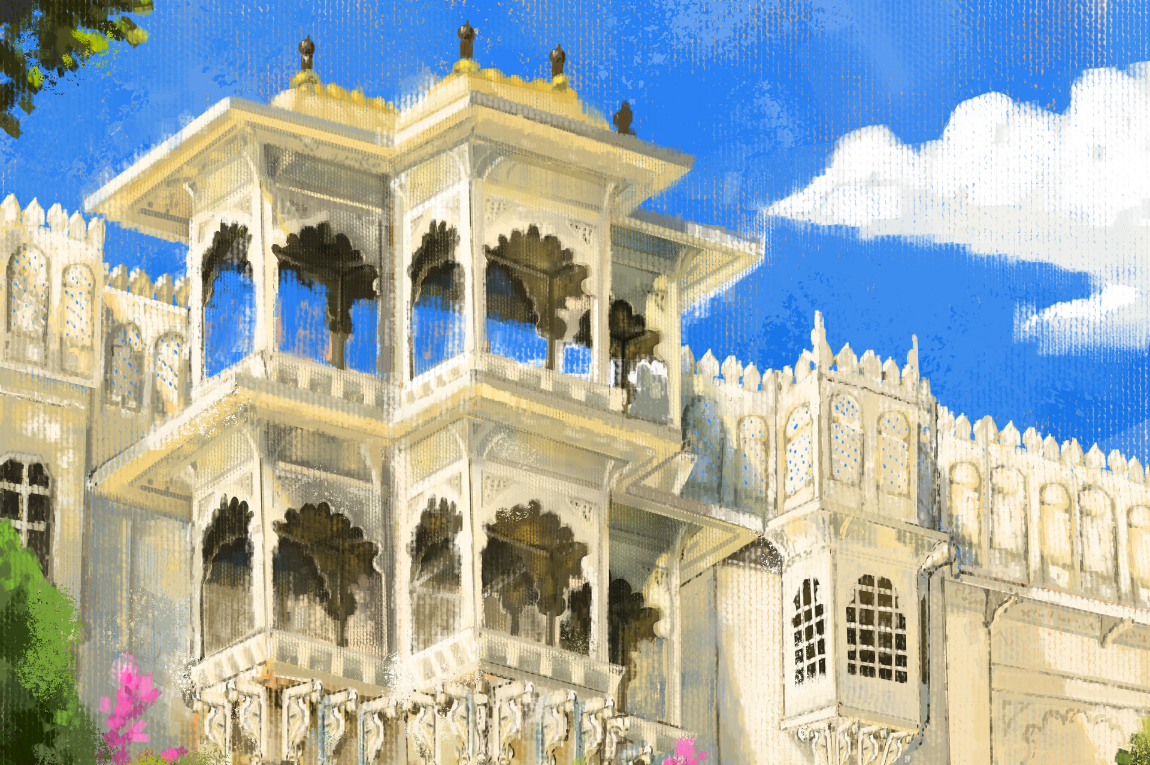

While walking through the narrow streets of Udaipur, a city teeming with palaces, havelis and statues, the city appears frozen in time. Looking up at the old heritage buildings that loom over the streets, I spot a repetitive element, and arguably one of the most iconic features across Rajasthan at large: the jharokha. These are oriel windows, supported by ornate brackets, that protrude out of a building’s facade. It’s a favourite spot for selfie-takers — an activity I’ve both participated in and been witness to while scrolling through Instagram. And with the number of hotels and restaurants housed in heritage buildings in this old city, there are plenty of jharokhas to observe (and use as photo booths too).

The jharokha, as an architectural device, can be found across Mughal and Rajput architecture. While the exact origin of this kind of window is a bit muddy, research suggests it can be traced all the way back to the Mauryan Empire around 300 BCE. “Jharokha was an old Indian concept, and the idea essentially belonged to the region which extended roughly between the [rivers] Jammuna (sic) and the Tapti and the Banas and the Betwa,” explains R Nath, a historian specialising in Mughal architecture, in his work. “Its form too belonged to this region: the word jharokha appears to have been derived from ‘jala gavaska’ or an ornately designed window.” In contrast, Udaipur — and consequently the jharokhas we see today — came much later, in 1559, when the city was founded by Maharana Udai Singh II.

These windows also worked with the region’s hot and dry climate, protecting the residents of the palaces from harsh sunlight and letting in the cool breeze. But more than just a respite from the heat, they were also windows to the outside world for women in purdah, especially at places like the Zenana Mahal inside Udaipur’s City Palace.

Jharokhas can be easily spotted across Rajasthan and surrounding states like Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. Jaipur’s Hawa Mahal is well known for its 953 jharokhas. Mughal emperor Akbar, whose empire spanned much of the Indian subcontinent during his reign from 1556 to 1605, popularised the custom of ‘jharokha darshan’. He would conduct the day’s first official business, after prayers, from a jharokha that faced east, which allowed the public to see him at work every day. This was also a way of worshipping the sun — a more Hindu and Zoroastrian custom — which is said to have made his rule more favourable.

Across the region, this ornamental window adapts to the character of the place. In Udaipur, where the urban fabric comprises stone and white plaster, the jharokhas, with their engraved, multifoil arches, look delicate and pristine — a subtle contrast against the rugged mountain backdrop.

One of my favourite activities during my time in Udaipur was sitting by the window, watching the sun set over the Aravallis and the marvellous cityscape glimmer in the waters of the Lake City — all through the iconic frame of a jharokha. Udaipur may be engulfed in a cloud of popularity and prettiness for most travellers, but looking back on all of the jharokha selfies that are proudly clogging up my phone gallery, I’m fascinated to know that the story behind these stunning backdrops is, in fact, older than Udaipur itself.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Namrata Dewanjee is an undergraduate student at RV College of Architecture, Bangalore. She grew up in Kolkata and is driven by her interest in expressing her opinions through art and writing. Her journey through architecture has been a process of exploring different media and finding her voice. She is on Instagram at @namrata_dewanjee.

Emmanuel Augustine is an illustrator based in Kochi. He is on Instagram at @emmanuelagustine.