In her debut book ‘Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul’ (2019) author and journalist Taran Khan creates a personal portrait of the Afghan city after spending long periods of time traversing its terrain, between 2006 and 2013, as a reporter and training Afghans in video production. Here, she tells us why Kabul is an ‘amnesiac city’, why navigating the outdoors is complicated for most women, and the shortcomings of being a writer.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

If I have a tilt in my reading preferences, it is towards non-fiction. I think reality is interesting and challenging in a way that often defies the imagination. I am thinking of works like Hisham Matar’s The Return, which has stayed with me since I read it nearly two years ago. Or Svetlana Alexievich’s Zinky Boys, about the Soviet war in Afghanistan. My current reading list includes two very big books — Tawaifnama by Saba Dewan and The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India by Supriya Gandhi. In fiction, I was riveted by Shubhangi Swarup’s Latitudes of Longing; she writes in a way that is absorbing yet inventive. Like most children in India, I grew up listening to stories as a way of spending evenings at home — I love fables, folk tales, pahelis (puzzles) and muhavras (metaphors and idioms that often reveal a lot about the speaker’s world). I am, of course, reading about crisis these days but I am also reading more poetry than I usually do, including Ilya Kaminsky, Mirza Ghalib, Agha Shahid Ali and Paul Celan. The authors that I return to repeatedly are Alexieveich and Ryszard Kapuscinski, in addition to Italo Calvino for certain moods.

What made you want to be a writer? What do you think is the role of a writer?

I grew up in a joint family around lots of books — my parents were avid readers and loved to introduce the kids in the house to new authors. I also had the influence of my maternal grandfather, who was always surrounded by books, and who had been a translator and written plays and articles. This was in the 1990s, before liberalisation and the internet, and a time when print media and magazines carried a lot of importance. I remember spending hours reading the Sunday newspapers and thinking, “This is what I want to do”. It seemed to be a good way to be part of the world — by writing about it.

I think my job as a writer is to reflect on what I experience and hear, and tell those stories as honestly as possible. At the heart of this sentiment, I think, is the idea of empathy — a need to explore the many realities around us, and to connect with people who may seem completely unfamiliar.

Your book ‘Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul’, released last year, is a fresh counterpoint to the accounts otherwise published by correspondents from places of conflict. It grapples with tropes that seem specifically urgent today ― that of identity and gender. It is also autobiographically revealing. How did you maintain being private yet candid at the same time? Did you, at any point, feel you were sharing too much?

From an early stage I knew that this was not a book about me, but about the city. There have been many books about journalists in war zones, and I didn’t feel that was the most important story to be told here. Kabul was the heart of this story.

But it also made sense to use my own vantage point, as a way of making connections and explorations, and also for the reader to understand that this is my perspective. The key question I had to consider was if my personal voice was adding an insight, or revealing a different way of seeing the city. This idea guided my decision-making. For instance, I decided to write about my grandfather because he was so important in the way I explored Kabul.

You have been going back to Kabul on assignment since early 2006, working as a reporter and also training Afghans in video production. As you kept returning to the place over the years, what were the drastic changes that you noticed? Did you also experience any changes in yourself, as a person?

It was a time of flux and transformation. Over the years that I saw it — from 2006 to 2013 — the population of Kabul increased dramatically and its infrastructure could not keep pace. Physically, the city became bigger and spread out wider, expanding beyond its traditional limits. But because of the deteriorating security situation, the roads became narrower, encroached on by security apparatus like sandbags and concrete barriers. Many foreign workers had to live and work within secure compounds, and could venture out only in a limited way. At the same time, neighbourhoods that had been destroyed during the civil war were rebuilt, and Kabulis who had spent years living as refugees abroad built homes for their families.

I think being in Kabul made me more aware of how situations that seem simple can often be interrogated to reveal more complicated truths. So the easy narratives that dominate the discourse about places like Afghanistan are often quite meaningless on the ground. As a journalist, I learned the value of spending time in exploration, and the value of respectful listening. I also learned to trust my instincts and recognise that the stories I found were worth telling, even if they departed from traditional forms of ‘war-reportage’. Personally, I found the energy and enthusiasm of the people I worked with very inspiring. I learned a lot from them.

Could you tell us more about why you speak of Kabul as an “amnesiac city” in your book?

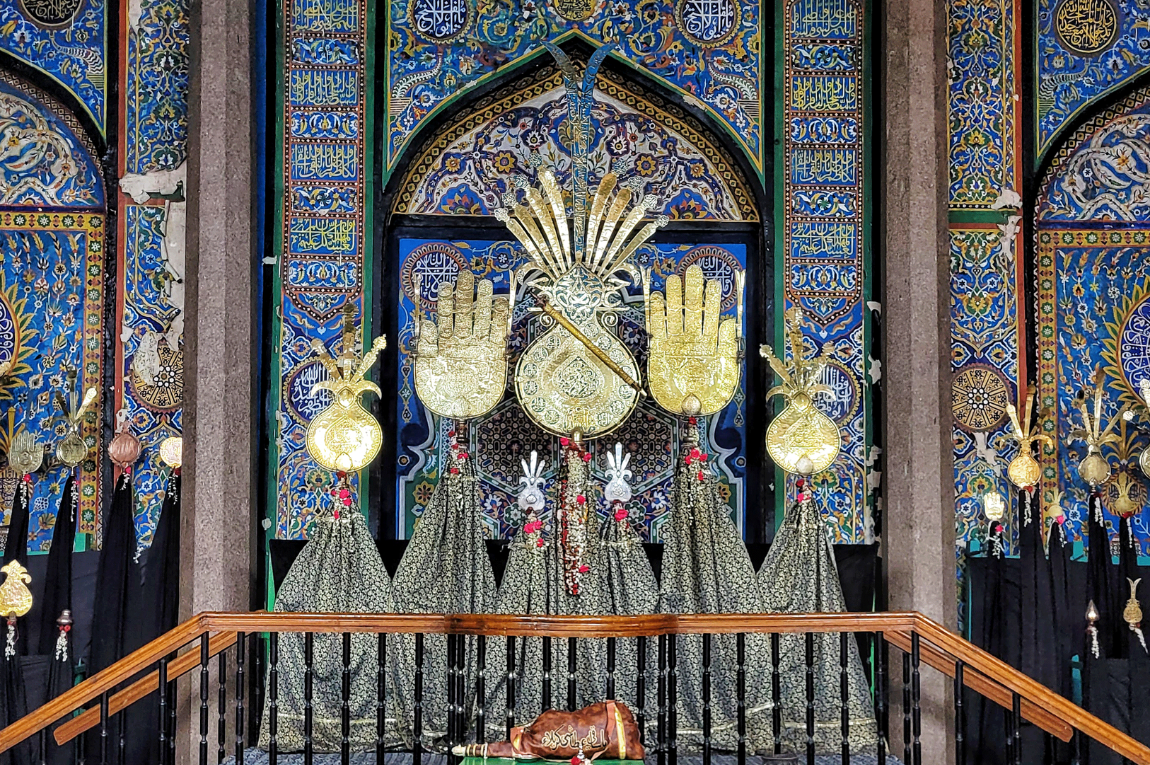

I read this description in a history of the city, and was struck by how apt it seemed. Kabul is a place where the past often seems obscured; something below the surface. This includes the physical remains of its history, as well as the intangible heritage of its culture. Many of the themes I explored revolved around this idea of a city with layers that are revealed in different ways. These were motifs I found recurring in my explorations — the idea simply being that there are memories and stories to this city beyond its more recent history of war.

In your book you also state that you have a “complicated relationship” with walking. Here, I am also thinking of Lauren Elkin’s book ‘Flâneuse: Women Walk the City’ (2016), and the way she combines historical research, critical analyses and memoir to bring to the fore how women artists and writers ― over the ages ― have navigated cityscapes, challenging the otherwise patriarchal practice of the flâneur. What were the apprehensions you had to confront, concerning the act of walking?

The outdoors is complicated territory for many women. In my case, this first became apparent in the urban landscape of my hometown in Aligarh. I often had to display a posture of work, or purposefulness, in my very stride, to show I had a reason for being out on the streets. I would recommend Why Loiter: Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets by Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade as a book that explores many of these questions from a south Asian perspective. In Kabul, walking was deemed dangerous for everyone from abroad, not just women. But being told not to walk was also a part of my particular experience. It was one more way in which this unknown city felt familiar.

You also mention of your familial connection with Afghanistan going back centuries. Did you ever feel compelled to abandon, perhaps temporarily, the current state of upheaval and unrest in the country in order to question its past?

I would say yes and no. The more time I spent in Kabul, the more strongly I felt the need to write in a way that communicated the feeling of being in the city. This was the stuff that was often left out of news or even feature-writing. I began working on longer pieces and experimenting with form and themes which revealed the potential for a book. After 2013, I spent long periods revising my work, to find the right shape for the material. I was keen to get this right because I wanted a structure that led readers wander in their own imaginations, while moving across spaces and time in Kabul.

How did you go about gathering, tabulating, and accounting for evidence and anecdotes as part of your research process? Did it change over the years?

I reported the stories between 2006 and 2013 on different journeys to Kabul. I also read deeply about the city, including accounts by other travellers — like the poetry of Muhammad Iqbal, and the iconic tourist guidebook by Nancy Dupree, An Historical Guide to Kabul, first published in the 1960s.

The alleged misrepresentation of traditional Afghan society in ‘The Bookseller of Kabul’ by Anne Seierstad created a furore a few years ago. Were you, at any point, in conflict about or wary of being a reliable narrator?

I made it clear that this book was my perspective, so I was comfortable with what I said, as the reader knew where it was coming from.

What, according to you, are the downsides to being a writer?

On a bad day, several. Besides the dual demons of procrastination and guilt at procrastination, I find that women writers tend to face self-doubt in an intense way. There are practical problems too, like balancing the schedule of being an independent journalist with longer writing projects that require dedicated stretches of time.

On good days, however, it is satisfying in a way nothing else is. For me, getting to do this work is a privilege. Even if I don’t always know the shape the text will take, I try my best to engage with the tasks of documenting voices and recording the stories around me as part of doing my job.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)