There are numerous ways in which a place blends into a work of fiction — breathing its own life, singing its own tune, mapping its own moments. These are places the reader may not have visited but through texts, the reader witnesses, wanders, meets strangers, lingers, and gets lost. They flit from page to page as if from street to street. We ask six writers to recommend books in which the places that characters inhabit become characters in themselves.

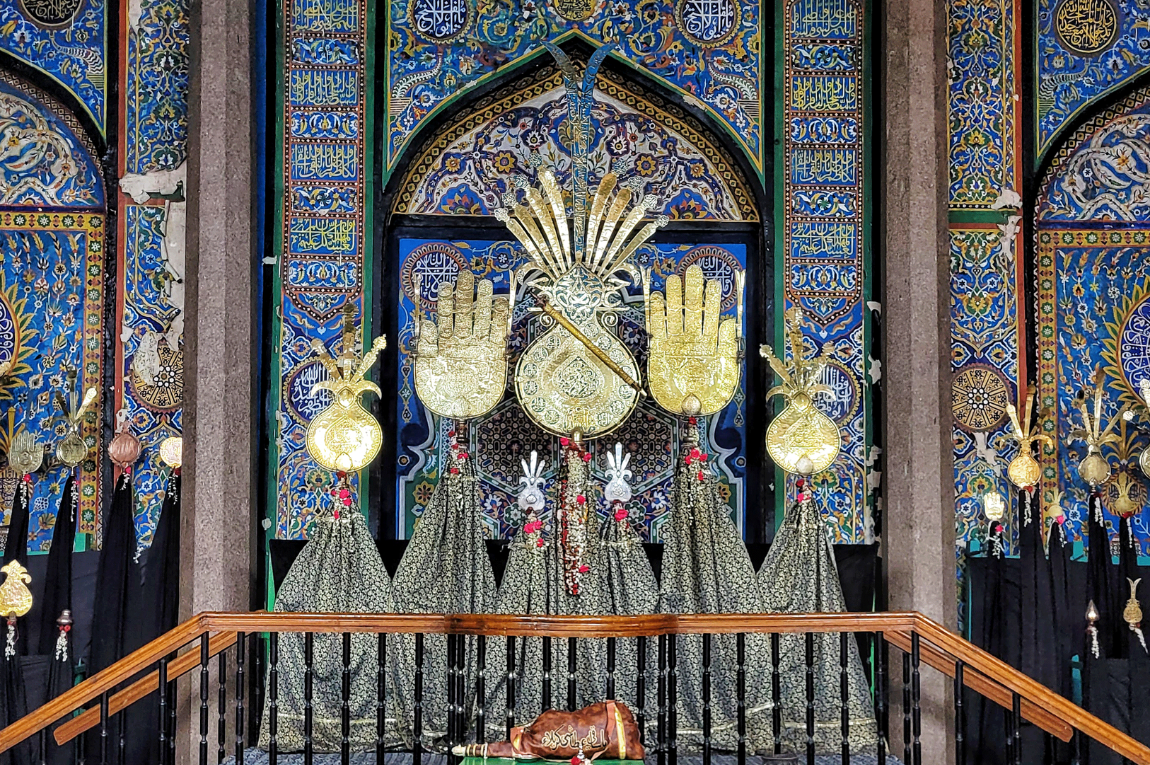

‘The Language of Baklava’ (2005) by Diana Abu-Jaber

Recently, on my first foray to the desert after moving to the Middle East, I was reminded of Diana Abu-Jaber’s powerful recollection of visiting a Bedouin village in her father’s native Jordan, where her family relocated from the United States. “Here, there is no such thing as time, there are only curling robes, high winds, undulating camels,” she writes. The dusty streets and desert sands of Jordan are not just the backdrop to Jaber’s story about the highs and the lows of a lifetime of straddling two distinct — and in many ways, disparate — cultures. Instead, the country becomes both the canvas and the muse, and food is the medium through which she paints this deeply moving story.

—Vidya Balachander, writer

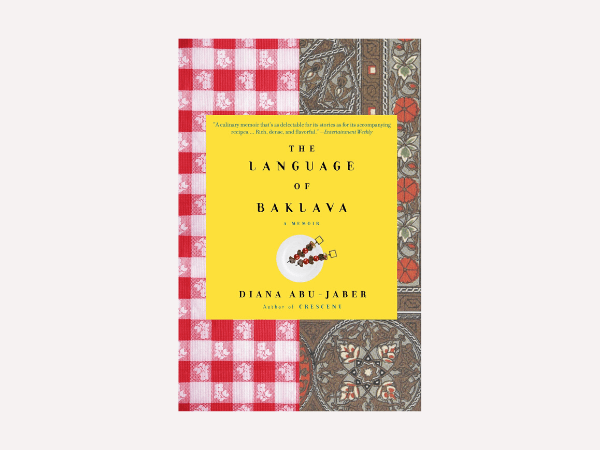

‘Watermark’ (1992) by Joseph Brodsky

Few of us recall that the word ‘tide’ is simply an older word for ‘time’. The splash of oar against wave, the line of breakers riding up to the beach, the stripe that the canal touches at its fullest, the relentless rise of the acqua alta that surges in from lagoon to piazza — all these are ways of telling what time it is, when it’s time, when it’s high time, or when we’ve run out of time. Nowhere is the relationship between water and time more sensuously, passionately or sumptuously invoked than in Joseph Brodsky’s extended love letter to Venice, Watermark. It has remained one of my favourite books for nearly three decades.

Weaving together anecdote and aphorism, painting a striking portrait of a Venetian aristocrat, recalling the exploration of a palazzo in magical semi-darkness or a long walk across twelve bridges, the Russian poet — who was imprisoned by the Soviet authorities and later migrated to the USA — invites us into the lived experience of a legendary, labyrinthine city. Brodsky recalls how Venice was a fantasy for him, when he was confined to the Baltic coast, and how he promised himself that he would visit there if he ever escaped to liberty. Eventually, he ended up visiting the city many, many times, spending extended periods and forming strong associations there. In Brodsky’s memoir, Venice assumes the dynamism of a person, wearing and discarding masks, costuming itself in different kinds of weather, transiting from one mood to another. The poet’s eye dwells on the winter light of Venice, cold and pure, the “caress of infinity”. It falls on little architectural details like the chimera with “the head of a lion and the body of a dolphin” that leaps out of a wall.

Venice is one of my own favourite cities, and I know the topography of several of its sestieri like the back of my hand. I love Watermark because it affirms my own deep love of Venice, which has been the scene of some key events in my life. “So you never know as you move through these labyrinths whether you are pursuing a goal or running from yourself,” writes Brodsky, “whether you are the hunter or his prey.”

—Ranjit Hoskote, cultural theorist and poet, Jonahwhale

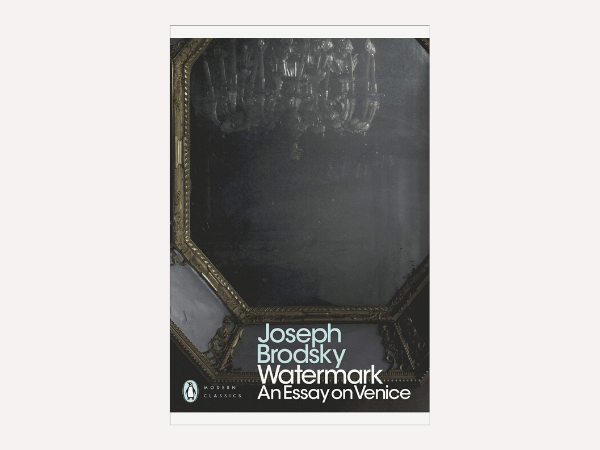

‘Kartography’ (2002) by Kamila Shamsie

Kamila Shamsie’s Kartography transported me to Karachi, a city I haven’t visited (and given the current political climate, hold scant hope of ever seeing) but which began to feel familiar within just a few masterful chapters. Upper-class Karachi, I learnt, is not very different from South Delhi, except for curfews and stray bullets and the memory and wounds of civil war. It is a multilayered novel about love, betrayal, family and history; it brings Karachi to life and also reminds us that walking through a South Asian city is walking through multiple cities, multiple histories at once.

—Amrita Mahale, author, Milk Teeth

‘Insomniac City’ (2017) by Bill Hayes

A great deal has been written about New York City, and it’s easy to see why. There’s the iconic skyline, its palimpsest-like history that continually builds with each successive decade — albeit much later than most ancient civilisations — and its chance to create and inhabit subcultures that allow everyone to feel at home. Insomniac City by Bill Hayes manages to find the corners and crevices that detach these themes while keeping things intensely personal. Hayes narrates the hold the city has on him, intertwining it with sharing a home and life with Oliver Sacks, the noted physician and science writer. There is a lot that’s overlooked, but for an uncannily generous look at the city, Insomniac City is a favourite.

—Aatish Nath, writer

‘The Peninsula’ (1970) by Julian Gracq

Last year, for three months, I was at the Institute of Advanced Study in Nantes, France, on the banks of the river Loire so I picked up an English translation of a book by the celebrated French writer Julien Gracq. The book, The Peninsula, is set in Guérande, 80 kilometres west of Nantes, abutted by a tributary of the Loire and the Atlantic Ocean on either side. It describes a man wandering around the Peninsula one afternoon while waiting for his girlfriend’s train to arrive. It is a slow, deep evocation of a place: seascape, inland, road, inn — all accompanied by shifting moods. While Proust comes to mind, this is a unique voice; more contemporary as well as a different shade of dark.

—Amrita Shah, author, Ahmedabad: A City in the World

‘Let the Great World Spin’ (2009) by Colum McCann

New York City is a challenge, a darling, a whimsy for any author who wants to capture its irreverent energy on the page. I return to Colum McCann’s novel Let the Great World Spin because he gets it absolutely right. The book opens on an early weekday morning in the Financial District, where the previous night and present day are still fused together, and office-goers are too sleepy for conversation but too wired to move slowly. McCann marks this transition from stillness to movement through pieces of trash, umbrella tips, sneakers, and revolving doors that “pushed quarters of conversation out into the street.” Every line makes me nod in recognition — and cringe with envy — at McCann’s physical and emotional precision. (“Quarters of conversation”! Isn’t that just genius?)