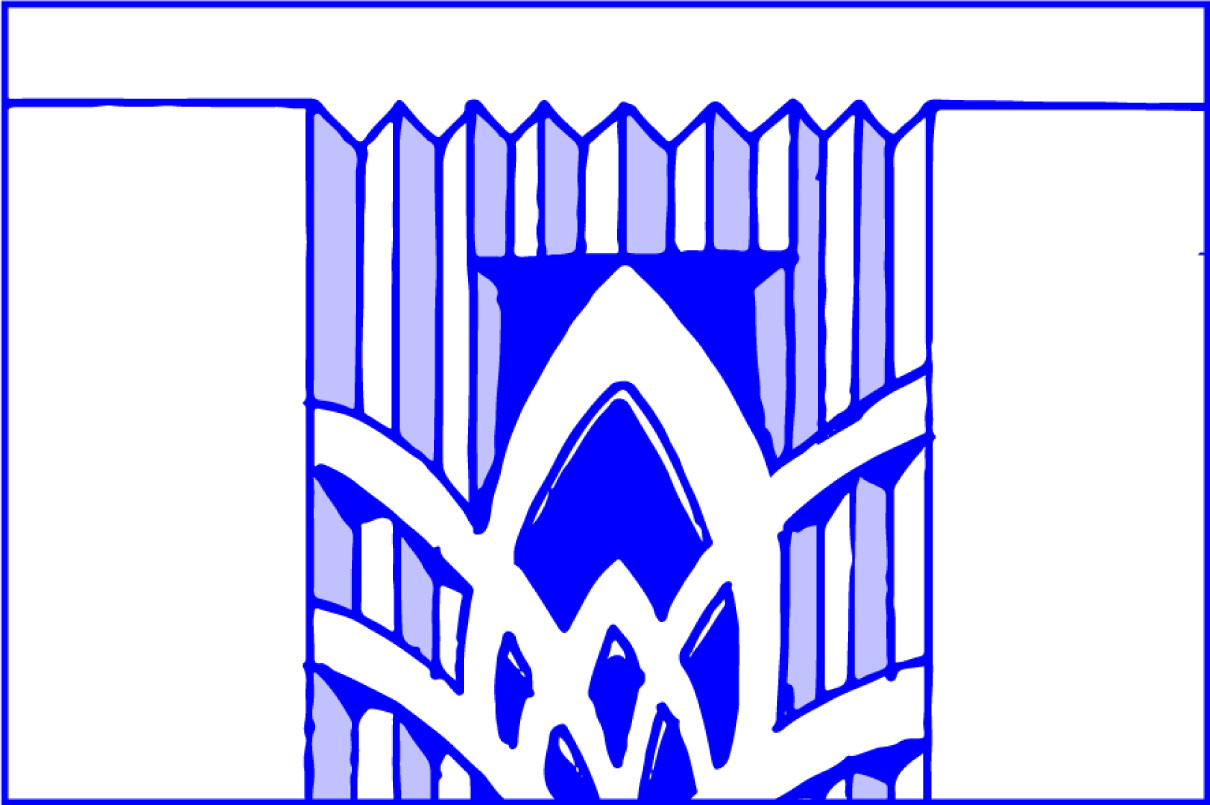

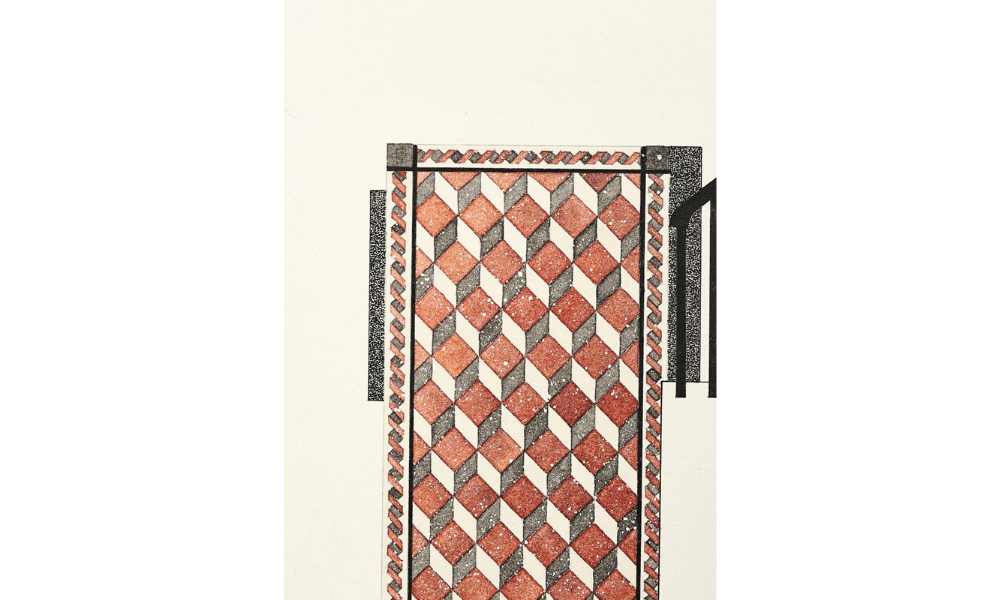

Artist Vishwa Shroff’s observant eye barely ever misses an intricately detailed balustrade, an absent tile, or a nondescript partisan wall. Her practice is firmly rooted in drawing; Shroff’s works are currently on display at Bombay’s TARQ art gallery. She has also conceptualised and designed — along with Katsushi Goto — the set for the play ‘Guards at the Taj’ (2017) directed by Danish Husain, weaving together the architectural facets and histories of the Taj Mahal, the space the actors occupy on stage, and the narrative of the play that oscillates between the worldly and the imaginary. Here, Shroff tells us about the books she loves to return to, the idea of exploring domesticity through drawing, and why stepping out for a walk can be a crucial starting point for making a work.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I’m currently in the middle of reading Time, edited by Amelia Groom, from the Documents of Contemporary Art series [an editorial collaboration between London’s Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press]. One of my go-to books is Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays by Robin Evans and my all-time favourite is Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll.

When did you first start developing a sense of curiosity towards spaces, to find out more about what lies behind and beneath and beyond an apparent surface?

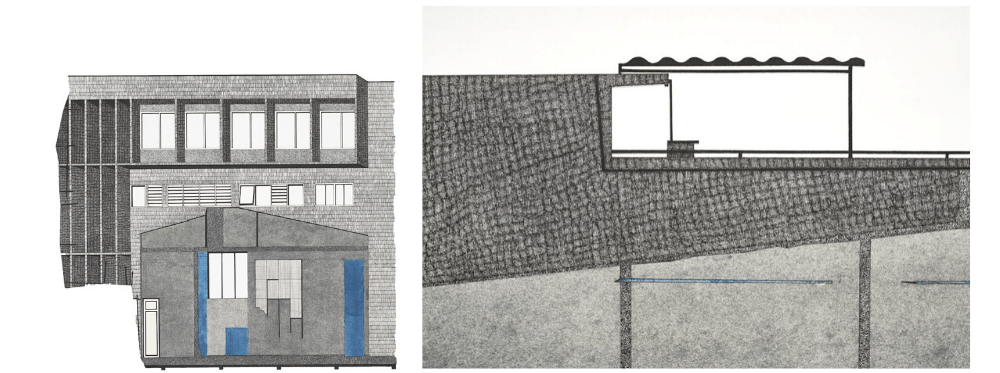

My parents started to build their new home sometime around 2007, which led me to be in and out of the architect’s office and to the construction site. At the same time, the house I grew up in was demolished. I think both these events, along with the influence of architect Karan Grover — who has been my mentor — unconsciously guided me towards looking at spaces as well as at objects within these spaces. I sometimes joke that architecture chose me, as I don’t quite remember a specific moment when I started to think about it. But looking back, I think this must be it.

You’ve lived in multiple, vastly distinct cities ― Baroda, London, Tokyo and Bombay. Has the transition from one place to another also changed the way you work, or the way your work takes shape?

I’m sure it does! It is something that has been pointed out to me several times, but the changes in the way I work are slow transitions that I don’t think of consciously. I believe that while these cities are different [from each other], pigeons are everywhere and just like them, the aspiration of cities and their transforming nature is a common thread. This is what I am interested in — how these seemingly disparate places are, at their core, similar, both in being cities of dreams and in historic analogous developments further accelerated by colonial movements.

When you’re drawing, do you think at all about who would be seeing your work? What would you like a viewer to take away from your work?

When I draw, I think about the methodology of drawing employed by architects, craftspersons, furniture makers, toy makers, and artists such as Rachel Whiteread and Zarina Hashmi, and even in Manga comics. I think about the curious marks and personal clutters that begin to quietly tell our stories, and about how I want to express these stories through drawing. I hope I am able to convey and transmit the intrigue of mnemonic connections that spaces hold!

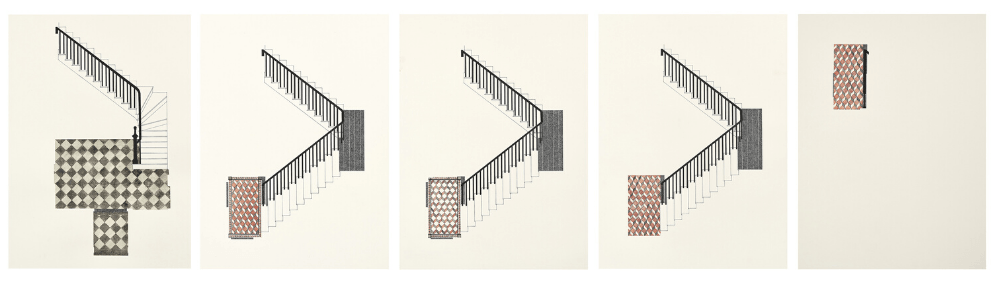

When you return to the same places/spaces — for instance, your drawings of the floor of the Victoria & Albert Museum — do you see things differently? Not just in terms of the physical space but also the potential it offers to experiment and iterate, or that it might be a crucible for stories that haven’t been explored?

Always! When I return to places, several questions play out. Did I do it right? Have I missed anything? Can I document parts of it that got left out the last time? Should I document it differently this time? How can I get more detail? But most of all I wonder how it’s changed since I was there last and whether this change brings out yet another narrative.

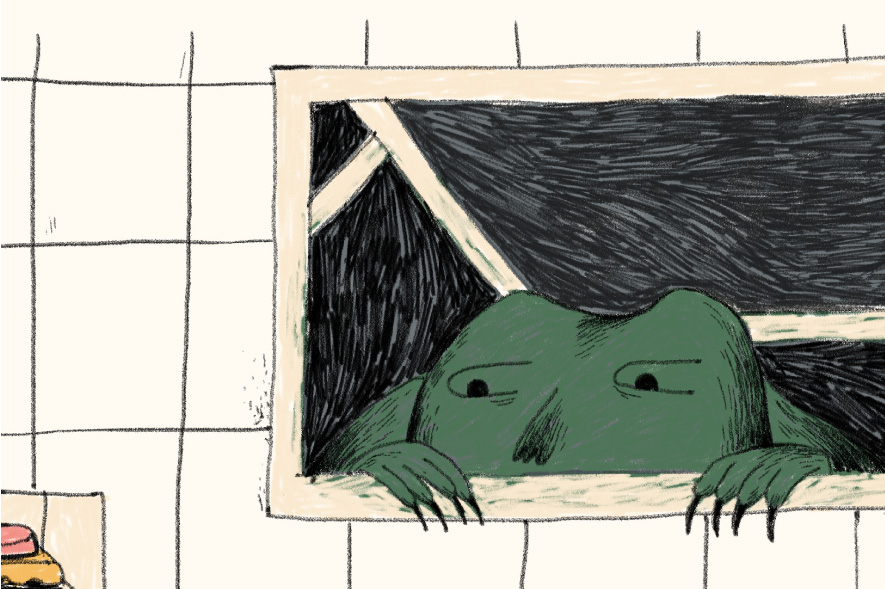

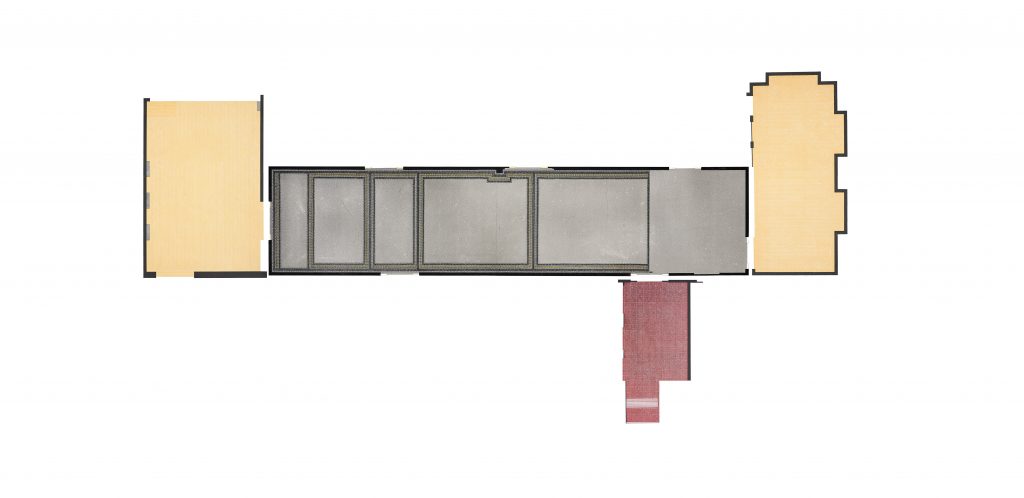

There is a lack of human figures in your drawings, except for perhaps the series ‘Everyday Rossana’ (2018) from the current exhibition, a playful rendition of a conversation between two people ― represented by two black dots ― who move within a space over a period of time. We are eager to know what sparked this. Could you tell us more?

‘Everyday Rossana’ is a study of movement within a domestic space that was mapped during Square Works Lab (SqW: Lab), a fellowship programme that I co-direct along with curator Charlie Levine, writer Rossana Van Mierlo, and my architect husband Katsushi Goto. The fellowship is an exploration of domesticity in all its possible variants done through the medium of drawing. It is in this context that ‘Everyday Rossana’ studies and explores the notion of permissions and thresholds that one encounters in a house.

Do you have a preparatory process for each work? When do you know when a work is finished, or when you’re satisfied with a drawing?

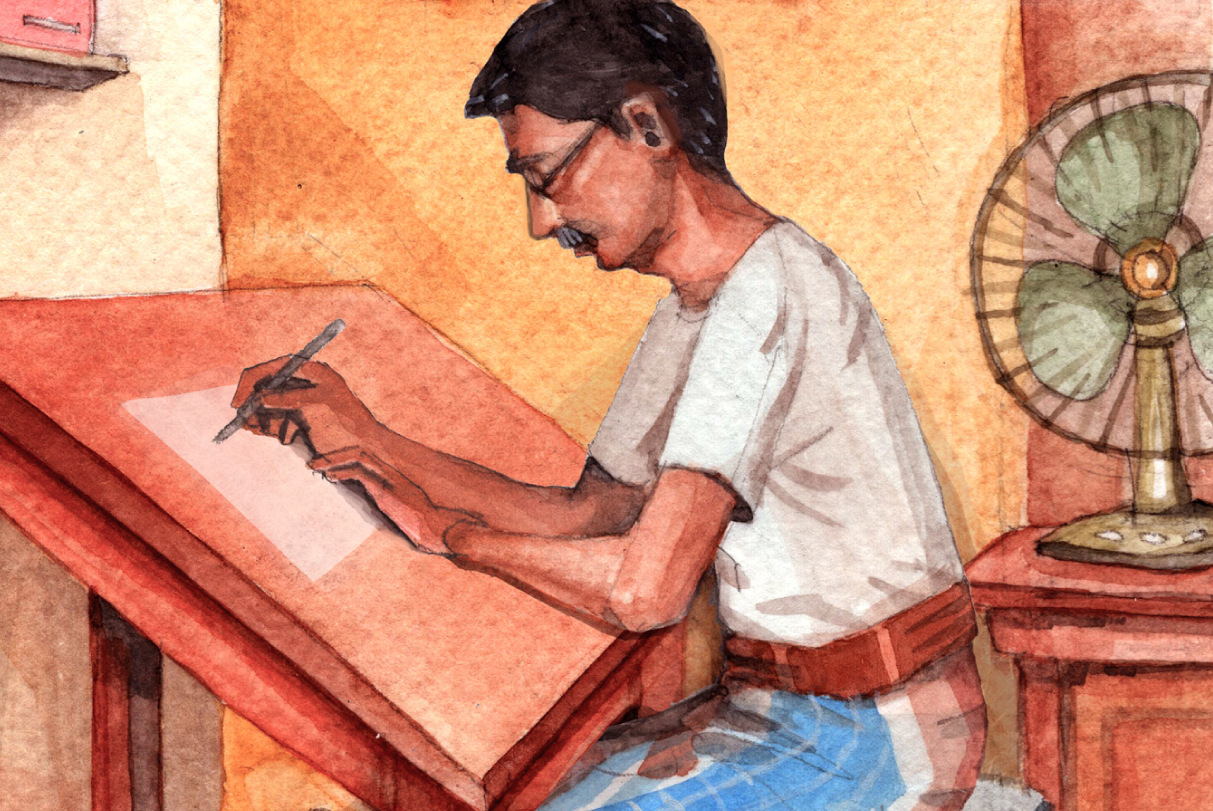

My preparatory process starts with going out for a walk and finding spaces that work as time-markers. I document these using photographs which I bring back to my studio and then use various tools to convert them into drawings either within my sketchbook or on graph sheets. These are then traced and redrawn on to the final paper I will work on to finish the works. Because the process takes time to reach this stage, I have usually worked out a mental image of what the final result would look like. Barring material experiments, I strive to achieve this and then I know the work is finished.

You have been experimenting with different formats ― for instance, the form of the book is an intrinsic part of your practice, with ‘Room’ (2011) and ‘Postulating Premises’ (2015) created with Katsushi Goto. Does the book act as a starting point for a larger set of works when it comes to questions of scale?

The books are a culmination of conversations that Goto and I have about both our practices at a certain point in time. While we both have very individual concerns, we find that there are overlaps that have the potential of becoming concrete convergence points that we are able to work with collaboratively. Since it is an extension of an ongoing dialogue, I suppose they do become starting points for larger sets of works, or maybe they are an end of one such conversation. This year, I think, we have reached a place where we will make a book and I’m eager to see how it will affect my work.

How did the idea of the Square Works Lab (SqW:Lab) fellowship in Bombay come about? Having been an artist-in-residence, what is it like to be hosting artists and creative practitioners who come together to collaborate? Has this also influenced your own practice?

Goto, Charlie and I had been having a conversation about drawing, domesticity and spatial narratives since 2011 and have collaborated on several projects since then. These include ‘The Tale Tellers’ ― where artists and writers had to interpret their favourite stories, songs or poems via a series of images that represent plot points within that story, and ‘Cornered Stories’ ― exploring the possibilities of a corner through words or illustrations. We always dreamt of expanding our conversations and projects in a more formalised manner. We then met Rossana Van Mierlo in 2016 and realised that she, too, had been exploring similar concerns. When we moved to Bombay in April 2018, we had the space to do it. The fellowship programme is just in its second edition, so I feel it might be too soon to tell how it is going to affect my practice. However, you can keep in touch with us about the programme on its website (sqwlab.com) and can hopefully see the progression for yourself.

Which city would you wish to explore next, to perhaps gain inspiration from for a future body of work?

As many as I can and definitely those that have had British/ colonial grandmothers! I recently met a lady from Argentina who, in her home, has the same tiles as those I have drawn in one of the ‘Bombay Stairwell’ series. I haven’t thought about Argentina earlier, but now I wonder whether there are more links between Bombay and Argentina. Similarly, I’m interested in historical cultural transferences that have taken place, and how the selective amnesia of our history changes the narratives that shape our identities and how we then think of ourselves. But most of all, I want to find these links that exist as material evidence before they all disappear.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)