Welcome to Pantry-Trippin’, a column in which food writer Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi unearths the cultural connections of cookware and other kitchen paraphernalia from around the world.

There are a few ways to put chopsticks in context. Let’s begin with some simple numbers.

There are a hundred and ninety-five countries in the world. Citizens of only four use chopsticks as a primary eating utensil. In 2015 — according to Q. Edward Wang’s book Chopsticks — this number added up to 1.5 billion people. Add seven other countries who also use chopsticks for specific foods such as noodles and rice — and about one third of the world’s population has a pair of chopsticks on their table today. (As many people use a knife and fork as cutlery.) Humans who employ chopsticks use 50 muscles, 30 joints, and thousands of nerves between their shoulder, arm, wrist, hand, and fingers to move food into their mouths.

This effort is clearly not a deterrent. In 2006, 25 billion waribashi, better known to us as disposable chopsticks, were used in Japan. That’s 200 chopsticks per person per year. Laid end to end, they would circle the equator 250 times. Most of these are manufactured in and imported from China. According to a report in the South China Morning Post, the country produces 80 billion disposable chopsticks a year. To break it down, that’s about 220 million chopsticks a day. To manufacture them, the equivalent of about 20 million 20-year-old trees need to be cut every year. Each tree yields about 4,000 chopsticks — enough for the annual consumption of twenty people in Japan. Concerns about the ecological footprint of waribashi has led to a few BYOC (Bring Your Own Chopsticks) movements in both China and Japan. At least one company — Vancouver-based ChopValue — is up-cycling them into beautiful Scandinavian-looking furniture, hexagonal wooden tiles, and yoga blocks.

To be fair, BYOC is how these dining sticks came into play. The invention of chopsticks is credited to Ta Yü, the founder of China’s oldest dynasty, the Xia. He’s also more popularly known as the Tamer of The Flood. According to Chinese Mythology, he took the help of dragons to dredge soil such that the swelling waters may find a way to the sea. Controlling floods is imaginably both rushed and difficult work that leaves little time for leisurely meals. The story goes that around 2100 BCE, Yü picked up a pair of twigs to hastily scarf down hot food directly from a wok, little knowing that he was triggering a torrent of tableware for time to come.

Yü may be the stuff of legends and myths, but the more practical explanation for chopsticks’ existence is safety and speed in the kitchen. Indeed, chopsticks version 1.0 were most likely a pair of twigs or thin long bones designed to reach into boiling water or oil in the kitchen. Like many cooking implements, they were created to protect human fingers. It took about four millennia and a population boom for them to travel from the stovetop to the table. Feeding more people demanded efficiency in food prep, and so food was cut into smaller pieces for faster and more even cooking, making table knives somewhat redundant. Chopsticks were cheap, easy, and quick to make — enough reason to abandon other forms of cutlery.

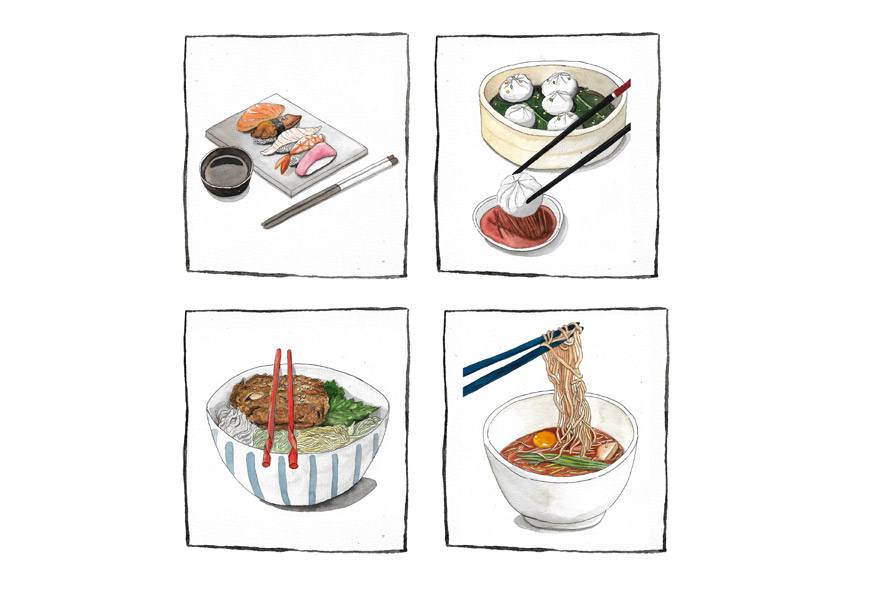

Chopsticks, as they are wont to, moved fast — even though they can sometimes slow you down and make eating more mindful. (The root of the word, in fact, may lie in the Pidgin English and Cantonese words for ‘haste’ according to this snappy but intense analysis by the UPenn-hosted linguistics blog Language Log). By 500 CE, they could be found on tables in other parts of the continent — specifically Japan, Korea and Vietnam, mainly due to the Chinese cultural influences in the area. And since, chopstick design has evolved to suit local regional foods both in size and the materials used to make them. Chopstick etiquette symbolism is a book unto itself: In China, for example, poking around in a bowl looking for a particular morsel is akin to digging one’s own grave; tapping them on the edge of the bowl makes one look like a beggar seeking alms; and if kids aren’t deft with their sticks, it’s telling of their upbringing.

Of course, for those among us who aren’t Chinese kids, modern design has not only made handling chopsticks easier, it has also made them collectibles, taking something that started out as twigs in all manner of weird and wonderful directions. Klutzy design nerds seeking luxury and convenience will gain from and relish the irreverent sculptural tong-like Tukaani (€498.75) by Finnish-Ugandan designer Lincoln Kayiwa, inspired by the toucan’s bill. Those with somewhat smaller budgets will enjoy the spare genius of (and the a-ha moment behind) the $5.95 Gravity Chopsticks 2.0. The business end of these implements levitates off the table for hygiene purposes, eliminating the need for a chopstick rest. Nendo’s Rassen ($30) entwine into a single beautiful tapering cylinder. In 2007, Wired recommended Laura Rittenhouse Studio Furniture’s Chork as training chopsticks because $17 was “a small price to pay for a clean shirt”. There are even chopsticks to feed an OCD. If you love the spork, you’ll find chopsticks mash-ups aplenty with the spoon and fork. One artist uses them as his sole painting tools.

Chopstick geekery, if you’re keen on it, can take you down the rabbit hole. In the process of researching this piece, we’ve seen things we cannot un-see. If you always wanted to watch a cat eating noodles with chopsticks, take a look here. Among chopsticks statistics, this kitty is singular.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)

Roshni Bajaj Sanghvi, a graduate of the French Culinary Institute (now International Culinary Centre) in NYC, lives in Mumbai and writes mostly about food and travel for many a publication. She’s a contributing editor at Vogue magazine, and her words have also been found in Condé Nast Traveller, Mint Lounge, Scroll.in, The Hindu, Saveur, The Guardian, and Travel + Leisure, among others. She’s crazy about obscure ingredients, and she always knows where to go back for seconds. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @roshnibajaj.

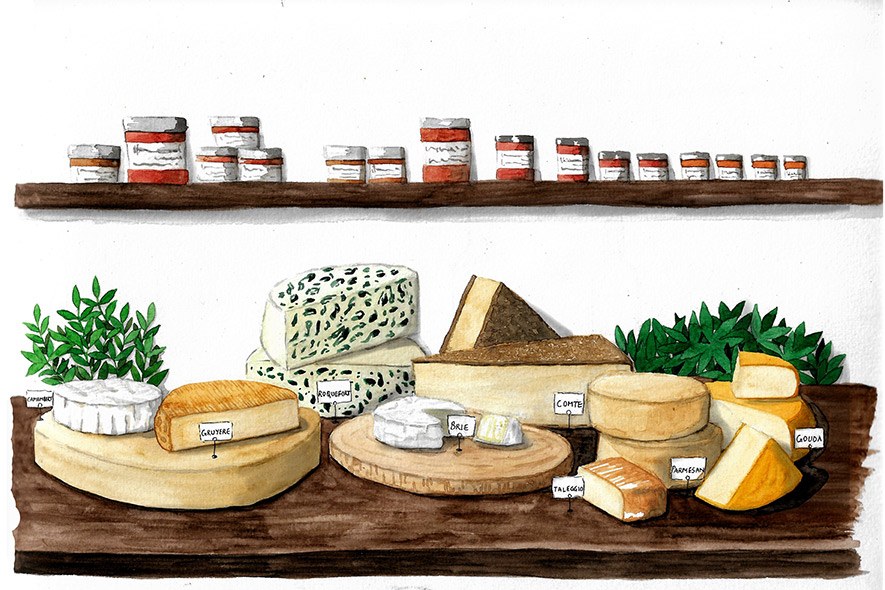

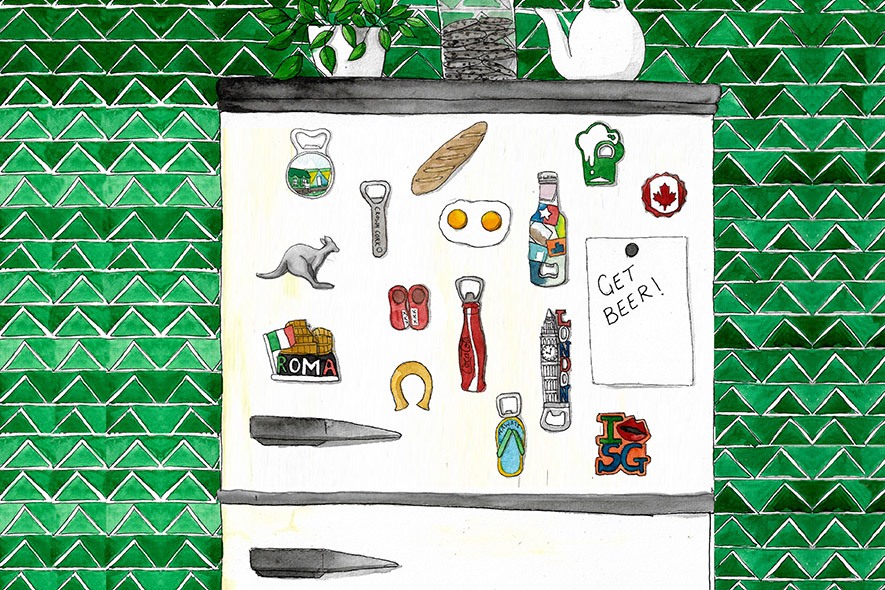

Shawn D’Souza is a textile designer who moonlights as an illustrator. He draws as a way of understanding his surroundings better. He is on Instagram as @dsouza_ee.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.