Indian cities are monumental archives of decades upon decades of bad design, stacked up tall into the sky with people living one on top of each other, as if for good luck. But a city doesn’t have to be a place duelling between a growing population and a finite amount of resources, or one that is riddled with pollution, garbage, chemicals with a side of food, or a lack of any sense of community. While most seem to have accepted this as the norm, a few are seeking solutions to this pervasive urban conundrum in the way of permaculture design.

It seems imperative to define what permaculture is before we proceed, and I do so cautiously — there are as many definitions as there are practitioners. Permaculture is an approach that addresses situations with a set of design principles and ethics, whose aim is to create systems that are regenerative, resilient, and self-sustaining, which care for human needs, as well as the Earth and all its living beings. Contrary to popular belief, it is not, in fact, “just gardening”.

Take Monks Bouffe, a social enterprise that works towards highlighting the importance of safe food, nutrition and ecological farming, co-founded by Gaurang Motta and Saurabh Motta. While their company works with farmers directly to create products like peanut butter and moringa powder, they have used permaculture to help design the organisational structure of the company itself. “The whole process of designing the enterprise — the business plan, the way we make decisions — is based on permaculture principles. Thinking holistically and not having a single-track approach [like monoculture, which refers to the cultivation of a single crop in a given area] is what we try to practise, and it comes from the understanding of permaculture,” Gaurang says. The enterprise places a heavy emphasis on working with like-minded people, and collaborating with people who add value to the organisation — a great example of ‘catch and store energy’, one of the permaculture design principles. For Motta, organisational permaculture holds the answers to many issues prevalent in conventional corporate structures.

While permaculture can be so much more than just toiling in the field, for some, it is very much the foundation upon which all else is built. Ananas, for instance, is an ecological landscape design firm in Bangalore. Founded by Himanshu Arteev, who has a background in sustainable architecture and landscape design, Jananee Mohan, who studied design at NIFT, and Kiri Meili, who has studied environmental social sciences, the firm uses a permaculture approach to all their space and system designs. They also bring permaculture to Bangalore’s urban commons. In 2017, they started working with the space around the city’s Jakkur Lake to design a vegetable garden and two forest gardens (a kind of garden that aims to recreate how a forest grows). “The idea here is to grow food and [cultivate] an edible landscape so the people who use the lake — the fisherpeople, gardeners, walkers and runners — get a yield. We want people to start interacting with these public spaces,” explains Meili. “While initially we were focused on how to grow as much food as possible, our challenges indicated that there were way more social, cultural and people dynamics to meander through.” From addressing ideas of ‘ownership’ of the commons and who’s responsible for them, to reintroducing lost and forgotten species of edible plants into the garden and diet, today, a small, diverse community comes together to plant, harvest and maintain the ongoing project. It is also open to volunteers on certain days, when anyone interested can help out.

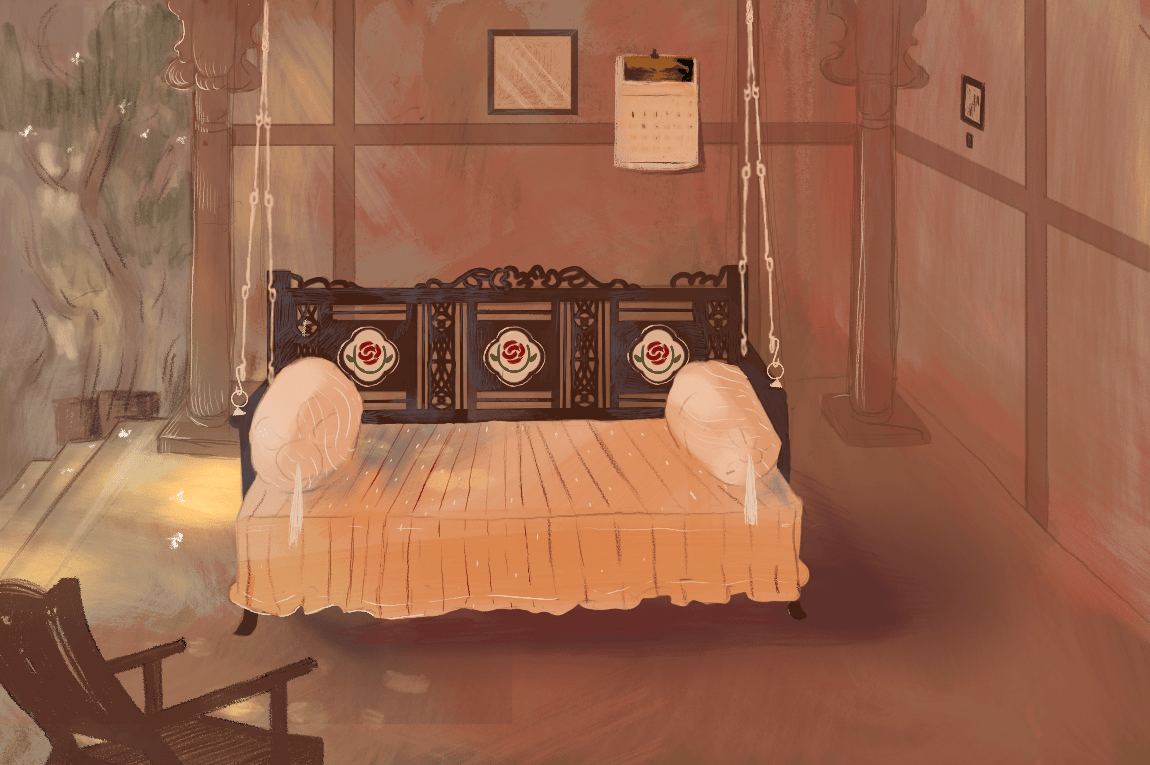

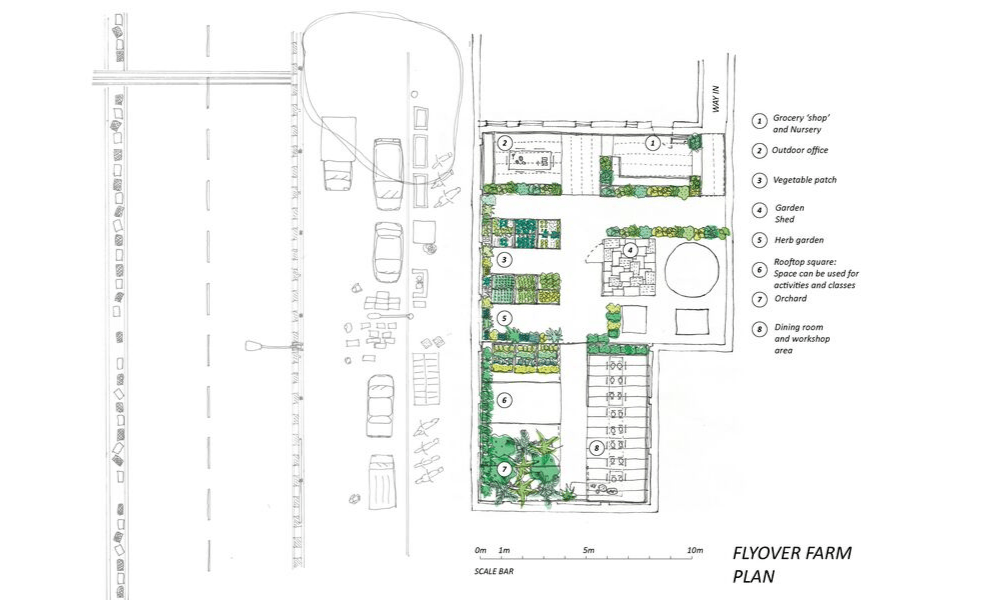

A cornerstone of permaculture design is understanding its key design principles, and how they work together to achieve a particular goal. Two of the twelve permaculture design principles are ‘observe and interact’, and ‘use and value renewable resources and services’. “We make a resource map of the site, draw out what’s around us and what’s nearby, and see how can we make the most of those resources before having to look for something further away that requires us to use transport,” says Adrienne Thadani, a permaculturist and farmer in Mumbai. At her ‘Flyover Farm’ project, a community-run rooftop farm that looks out over JJ Flyover, it’s observation that helped them identify the sugarcane and coconut vendors just below. All their leftover organic material that would go to waste is now chopped by the vendors and composted on the farm to build soil structure and microbiology — a classic example of how everyone benefits with just a little observation, interaction and design.

Urban designs are typically characterised by their small-scale nature — but a little is a lot, as far as permaculture goes. Thadani has also designed a permaculture garden in a 7m x 9m plot at Mumbai’s Breach Candy Club. This relatively small space contains a fruit forest with ‘guilds’ — groups of plants, fungi and insects that complement and support each other — at each tree, a section to attract pollinators, a relaxation space, and a vegetable garden. The confines of a space is simply a parameter for creative justice — and permaculture thrives on creative ground. Often, Thadani tells us, clients come in with ideas for gardens based primarily on beauty, but most are very open to the possibilities of a permaculture framework. While it may not be what they originally wanted, the idea of a space being more alive, where plants and animals work together to support life around them, gets them excited, she says.

As the climate crisis worsens, and natural cycles become more unpredictable, people are now looking at permaculture in urban areas as a problem-solving mechanism. Today, water is among the most threatened natural resources across the country, and permaculturist Fazal Rashid is working on a systemic solution to this crisis in Delhi. “We are in the process of designing a grey-water system for a four-floor home in which 1,500 litres of grey water will be collected on the ground floor, sedimented, and then pumped up to a constructed wetland on the roof. There, it will clean the water for their rooftop garden, kitchen garden, flush cisterns, and for cleaning cars.” This module of building systems to implement strategic design is at the core of permaculture, where resource management is key. While the grey-water system is admittedly expensive to build, Fazal says it is well worth it, considering how much time, money and water is saved in the long run.

Today, the urban conundrum is spiralling out of control — this much is true. With time, our most important resource, almost running out on us, it is of essence that we harness the creativity, curiosity and resilience inherently within us to make sense of our world. Maybe, just maybe, permaculture is the thing to get us there.

Further Reading

If you’re keen on discovering more about urban permaculture, you may want to look up The Permaculture City and Gaia’s Garden, both by Toby Hemenway. #permaculture on Instagram is also a good hashtag to follow for ideas and inspiration. Those who want to dig in further may want to sign up for a permaculture design course, which you can do online or in real life for about two weeks. Look for one near you — there are plenty available across India.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)

When Tansha Vohra is not scouring through recipe books and running to the garden every five minutes to check if her cherry tomatoes are ready or not, she writes. Tansha has done a Permaculture Design Course in Goa with Rico Zook, and has interned at a food forest where she was bullied by a rooster every single day.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.