What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I’m currently re-reading John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, and just finished a book on fungi loaned to me by a friend. I usually read one fiction and one non-fiction book simultaneously.

Every time I travel, I love reading a book by an author from that country or region. It gives me something akin to an insider’s view of the place. I also love cataloguing my favourite passages from books, so I can later re-live the experience.

When did you first realise that you were drawn towards nature? Do you have any particular memory that triggered your decision of foraying into making botanical illustrations? Did you always have a sense that this is the kind of work you would do?

I grew up in the city — in Bangalore — but as soon as the holidays were upon us, my family and I would head to the Western Ghats. From when I was younger than I can remember, the grown-ups would take us cousins on trekking ‘adventures’, even if we had to sit on their shoulders most of the way up. This led to an automatic association of nature with fun and freedom.

I was introduced to botanical illustration by my Aunt Iris, who would send us books and newspaper clippings from New Zealand, where she lived. The plant species were unlike anything I’d seen, and despite never having been Down Under, I conjured up a vision of what New Zealand looked like based off the images she shared with us. I think that gave me a sense of the power vegetation has to define the aesthetic of a landscape. In my mind, everything else — music, culture, art — were fundamentally derived from the natural materials available in that landscape.

I copied out nearly every illustration Aunt Iris sent me, but I don’t think I recognised it as a profession until much later. In fact I didn’t study art in college. It was only about a year or two after I started working that I began seriously painting.

Your work is deeply immersive, almost meditative. Is your way of working very structured or more spur-of-the-moment, or perhaps guided by the place you’re in, or your state of mind?

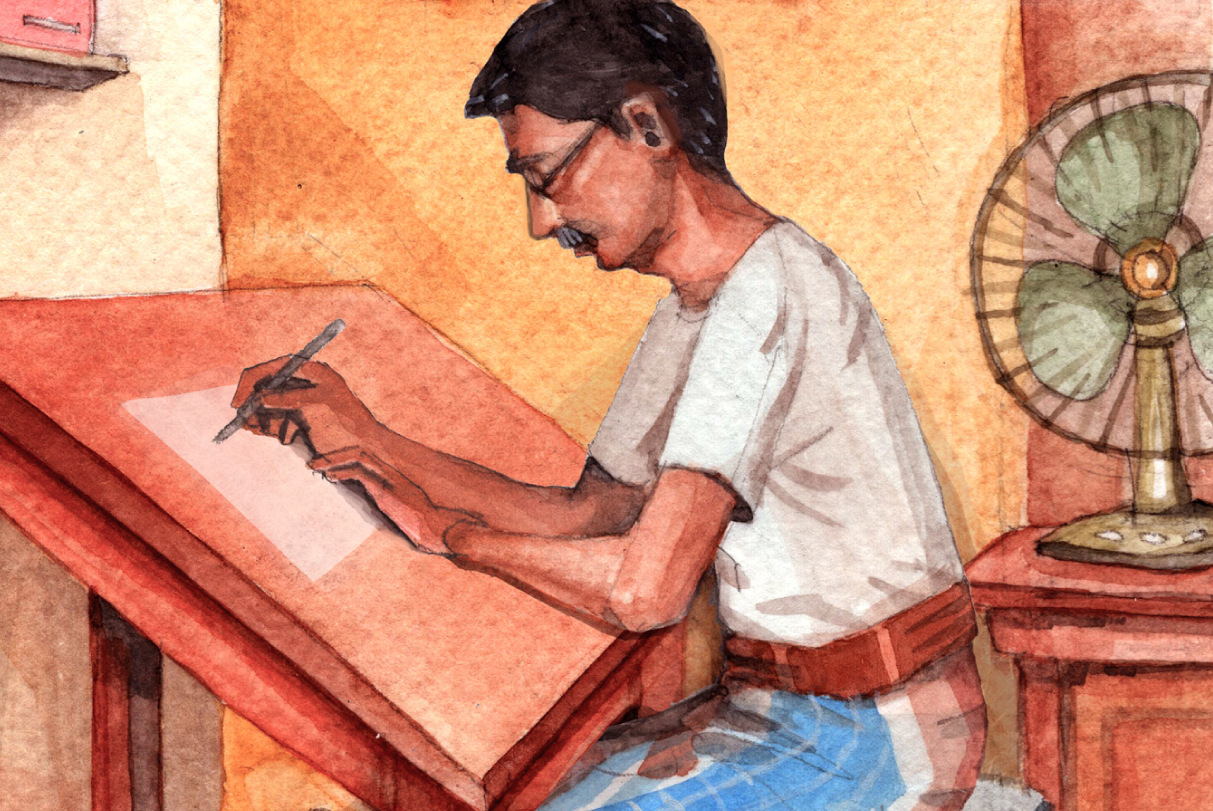

My way of working is quite structured. I always plan out what I’m going to draw, make mock-ups, then pencil outlines, and finally get down to painting. I like listening to podcasts and audiobooks while I work, and I like picking them to match the mood of the painting. I remember listening to a podcast on Spartan warfare while painting a particular carnivorous plant — while I recall nothing of the historical detail, that painting always reminds me of Sparta.

Have your travels influenced your creative process and imagination?

I like making observational sketches when I travel — temples in Vietnam, cheese vendors and beach bums in Mexico, Ottoman mosques and tulips in Turkey. On the surface, I guess botanical illustration can seem like a very literal representation of the subject matter. In a way it is, as it should be scientifically accurate. But I think my sense of colour and composition are greatly influenced by such experiences.

How do you go about recognising, observing and studying the many intricate details of the botanical world so as to bring them to life on paper?

My husband, Alok, always jokes about how I don’t notice anything but trees, and how I often use them as landmarks over buildings (he’s an architect, so perhaps he takes it personally :).

Do you ever sit down to work, and then face a block when you can’t proceed with anything?

Since most of my work is pre-planned, I face blocks while planning, but not usually while painting. Sometimes I’m just not in the mood to work, and I allow myself to take a break rather than work forcefully.

You’ve made 80 illustrations of rainforest trees for ‘Pillars of Life: Magnificent Trees of the Western Ghats’, authored by Divya Mudappa and TR Shankar Raman, and published by the Mysore-based Nature Conservation Foundation. You’re almost creating a profile of each tree; do you then also begin to develop a special affiliation with these trees?

Yes. For Pillars of Life…, I studied and sketched each tree in person in the jungle over a two-year period. When I first started the project, I wasn’t very familiar with the species we were documenting, and the jungle largely appeared to me as a sea of undifferentiated green. But over time I began to mentally extract each tree from its lush surroundings, and see it as an individual. Shankar Raman often said we were creating ‘portraits’ of these trees, and I think that’s true. I could probably still recognise each of the particular specimen I drew, should we meet again.

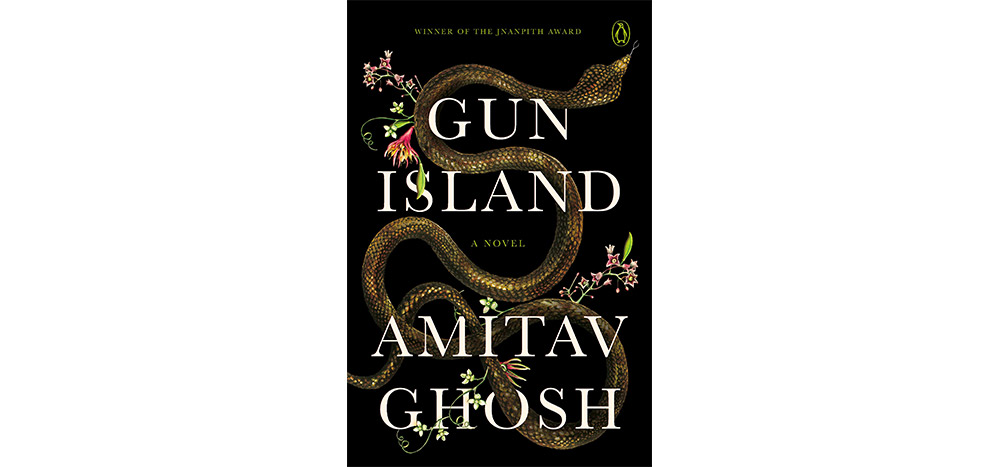

You recently created the illustration for the cover of Amitav Ghosh’s novel ‘Gun Island’ and also designed the re-jacketed editions of some of his previous books. Can you tell us a bit about the process of how you went about making the cover, based on your reading of the book?

Since Gun Island was such a high-profile novel, I wasn’t given the entire manuscript to read. I only had an excerpt from which to get a sense of the mood and themes.

Gunjan Ahlawat (who heads the design department at Penguin India), had the idea to involve a botanical illustrator to create this cover, since nature and the environment figure so strongly in Ghosh’s novels. That’s when he roped me in. They gave me the typographic layout and suggested the central motif of the snake, and asked me to intertwine the two. I added flora typical of the Sundarbans, where the novel is set. All the other book jackets we re-designed involve a similar layout, with nature-based motifs — migratory birds for The Circle of Reason, a hilsa fish and mustard flowers for The Calcutta Chromosome, an elephant and teak leaves for The Glass Palace, and a fishing boat and mangrove flora for The Hungry Tide.

Your skillset lends itself to an array of media. What are you seeking to do next?

I’ve just wrapped up another book on the Western Ghats, this time featuring the ‘fantastical’ plants of the region — like carnivores, and flowers that smell of rotting flesh. It’s intended to be one of the cross-genre books, which children and adults alike can enjoy. I’m currently in the US for a programme at Harvard University’s Dumbarton Oaks Research Centre, which looks at the intersection between botany and the humanities — how plants have influenced human history, and vice versa. In the future, I’m interested in projects that will allow to me communicate scientific or social-scientific subject matter to the general public.

You grew up in Bangalore. Do you have a long-standing familiarity with any trees in the city?

I love the giant rain trees (Albizia saman) that overhang so many roads in Bangalore. There’s one just outside my parents’ apartment that is taller than the building. If you are on the terrace, you can see into the universe it creates with its branches.

What was the last book you received as a gift? Do you usually gift books?

My husband gifts me books all the time. The first was a Diwali gift the year we began dating: The New Sylva — A Discourse of Forest and Orchard Trees, which is a beautifully illustrated collection of British species, published by Bloomsbury London, where I interned for two summers.

The most recent was a Christmas gift from my sister, Nandini. She gave me an illustrated book by cult Parisian apothecary l’Officine Universelle Buly, called An Atlas of Natural Beauty — Botanical Ingredients for Retaining and Enhancing Beauty.

I love gifting books too. Fiction only if I know the person really well, but otherwise books on a subject they’re interested in are great.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)