Grizzly murders, supernatural forces, femme fatales and larger-than-life criminals are par for the course in pulp fiction. For the uninitiated, the term may conjure images of a sultry Uma Thurman and “le big mac”. But the thrilling plotlines and eccentric characters in question are consistent with pulp fiction novels, named after the cheap wooden pulp or lugdi paper that was once used to print these books.

Around the 1970s and ’80s, pulp fiction novels were all the rage — especially in small towns — and were sought after by an audience that had few alternate forms of entertainment (TVs hadn’t arrested attentions just yet). Published in almost all major regional languages across India, these pastime page-turners were easily found at roadside stalls, second-hand bookshops and the omnipresent AH Wheeler bookstores at railway stations. In the ’90s, with the arrival of new forms of entertainment, the genre took a backseat. “TV arrived, and people stopped reading books,” says pulp fiction writer Amit Khan. The 44-year-old novelist, from Uttar Pradesh, who’s penned over 100 pulp books in Hindi, had his first story published when he was 12. He continues to write, but recalls a lull in his career back then. “A lot of publishing houses in Meerut shut down. I, too, had stopped writing for a while.” Meerut, he says, is where the major Hindi pulp fiction publishing houses were based.

Over the last decade, however, the genre has seen a revival, especially in urban areas, where there’s been a rise of pulp publishing translated into English from regional languages. Laura R. Brueck, a professor at Northwestern University in the USA who is currently working on the tentatively titled Vernacular Mysteries: Indian Detective Novels in the Reflection of World Literature, notices this as well. “I think there has been an interest recently — and not only in India — in reclaiming pulp fictions as an acceptable genre for people of all social classes and education levels,” she writes in an email.

Cover Story

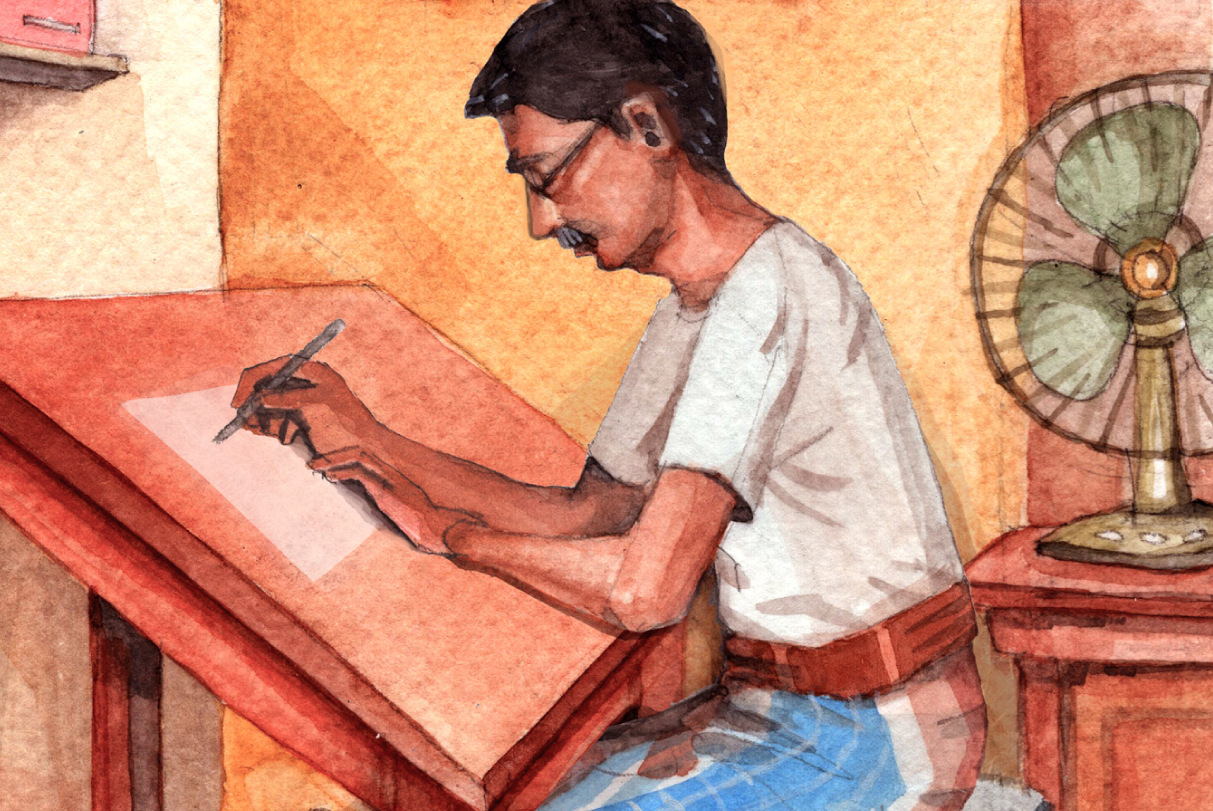

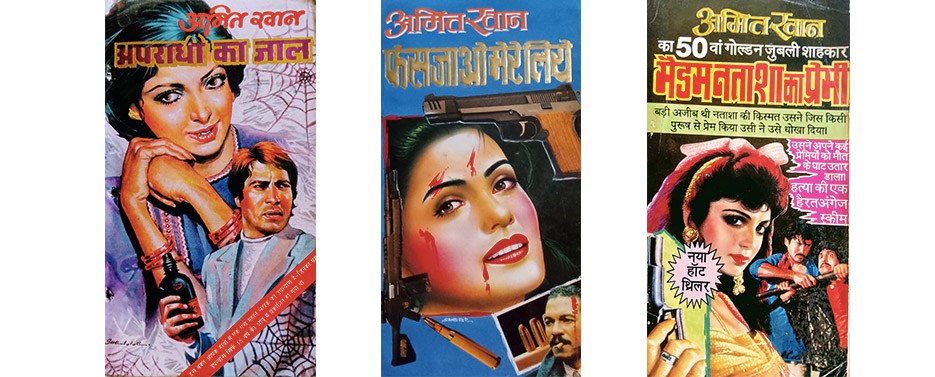

What’s always held sway for pulp fiction books are the covers. “These covers more often than not depict steely guns in the hands of similarly steely-eyed men, and women in various phases of undress and often also smeared in blood,” says Brueck. Lurid, titillating, and eye-catching — they were meant to attract the masses. “New readers pick up a book based on its cover and its title,” elaborates Khan. Moreover, these were covers that were vividly detailed and painted by hand. “We’ve had some great artists. Shelle, one of the greats, painted the most eccentric covers. So much so that if he’s making fingers or hair, they were amazingly detailed illustrations, incomparable to even photographs,” says Khan.

It’s hard to come by new pulp fiction cover art painted by Shelle — or Mustajab Ahmed Siddiqui, his official name — which is a shift that Khan puts down to the arrival of international publishers and a subsequent change in trends. Of course, in recent decades, the digital age has also disrupted old ways — Photoshopped designs are widely used. Brueck, “heard again and again that this kind of [hand-painted] illustration — like cinema hoarding painting — is dying out as an art form, certainly in part as a consequence of the ease of digitally manipulating online images.” Of note, during her research, were the Hindi crime novels she picked up from a small publisher in Meerut: Britney Spears and Robert Downey Jr. were the cover stars.

New Readers

This shift in cover design of pulp fiction novels is directly proportional to a shift in target audience and a more minimalistic style is seemingly preferred. “Covers that eschew the campy aesthetic more traditional to pulp novels are also paired with higher paper quality and better bindings,” explains Brueck. “These are clearly not meant to cater to the sidewalk or station buyer, but to a new audience that perhaps has a nostalgic connection to the purloined pulp novels of their youth, or who have a new interest in consuming forms of popular culture once considered ‘low-brow’.”

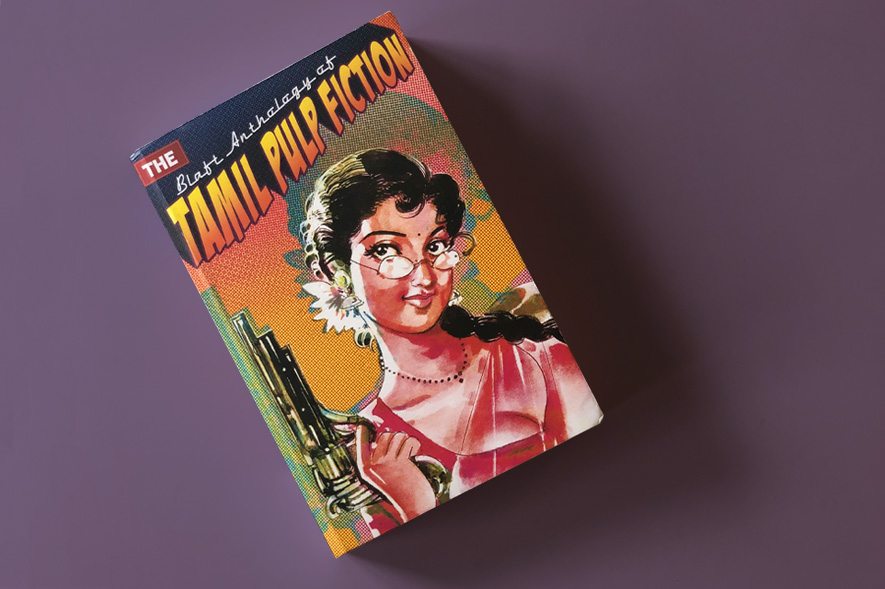

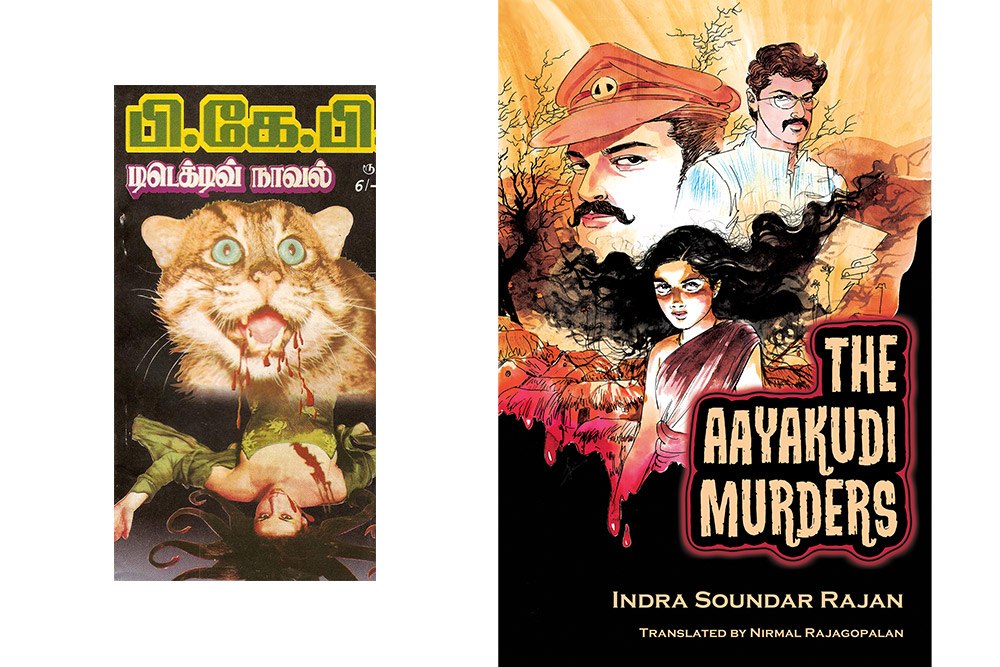

Interestingly, Blaft Publications, a Chennai-based publishing house, is still a champion of the traditional aesthetic in pulp fiction cover art. Since 2008, when they released The Blaft Anthology of Tamil Pulp Fiction (Volume 1), they have published two more translated anthologies of Tamil pulp as well as the English translation of Indra Soundar Rajan’s The Ayyakudi Murders, which just released earlier this month (July 2019). Rakesh Khanna, one of Blaft’s publishers and founders, is well-informed on the pulp industry’s winding trajectory. “Back in the late 1990s and 2000s, Tamil pulp publishers like Resakee and G. Asokan were bringing out lots of books with these amazingly wacky Photoshop covers,” he says. “The artists are sort of nameless and unknown — I think the publishers were directing them, and both those guys had a really hilarious approach.” Today, Blaft’s pulp books come with hand-painted cover art that harks back to the older style of the ’80s but with a twist for modern times as an attempt to “bring the feel of the originals through to the translated books,” Khanna explains.

Blaft’s go-to artist for their pulp covers is 42-year-old Shyam. “People come to me because of my speed and the fact I can grasp what they are looking for in an illustration,” Shyam says. “Even today I do up to twenty different pieces a day.” He, too, nods to a dwindling interest in the art form. “In the last twenty years, I have encouraged many artists to take up this kind of illustration work. I have even offered to train them, I’ve said they could use my studio space. But so far no one has come. I hope in the future more artists take this up.”

That said, it’s not doomsday for pulp fiction cover art. Far from being relegated to memorabilia, the style is in fact evolving.

Modern Pulp

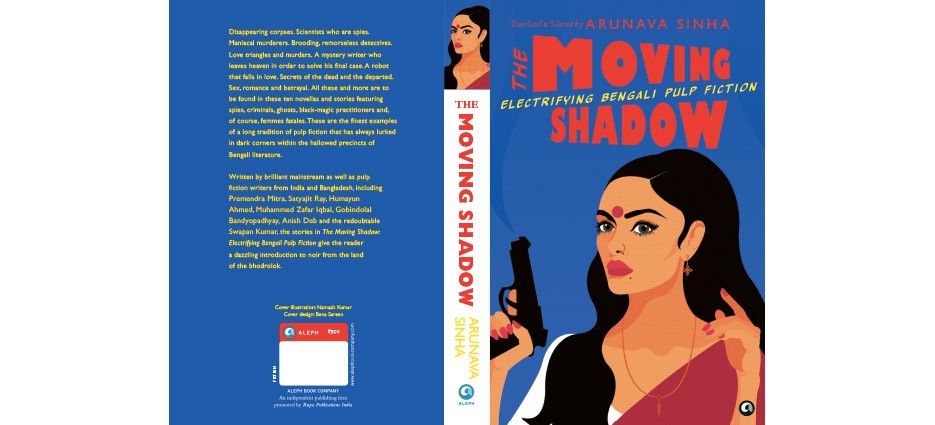

On the cover of The Moving Shadow: Electrifying Bengali Pulp Fiction, published by Aleph Book Company in 2018, is a woman on a mission, casually holding a gun. Designer Namaah Kumar, who made the illustration, wanted to pay homage to the “powerful portrayal of unabashed femininity married with female rage” of Rekha from Khoon Bhari Maang (1988). “One of the things that pulp does for the female character in literature is that it raises the stakes for them,” she explains. “Usually the femme fatale is highly sexualised. I wanted to move away from that because those portrayals can obviously be deeply misogynistic. One doesn’t need to necessarily defeminize a female character in order to not sexualise her. One wants to believe that audiences are becoming more sophisticated when it comes to things like the depiction of female characters.”

Kumar’s vision for The Moving Shadow is in stark contrast to previous, often objectifying, pulp fiction cover art. Brueck explains this well: “Cover art on the novels of some of Hindi’s most prolific authors — including Ved Prakash Sharma, Dinesh Thakur, Surender Mohan Pathak, Rima Bharti, and Anil Mohan — freely cite the vernacular aesthetic of lurid B-movie cinema hoardings prolific in mid-size Indian towns. Women are naked, or barely clothed, their garments torn and disheveled to reveal their hips and breasts. Brutalized women — with blood dripping from their lips and gaping wounds on their chests — are depicted in postures and with facial expressions more suggestive of sexual ecstasy than brutal violence. The men who brandish weapons in these images consistently look away, avoiding the gaze of the viewer, while gun-toting women look straight at you — smirking or surprised — inviting the viewer into an erotically dangerous imaginative exchange.”

Over the last five decades, pulp fiction cover art has seen immense change, both in its style and in production. “Pulp took root at a time where hand painting was the norm,” Kumar explains. Now, there are so many more ways of making covers. “While there is merit to keeping certain aspects of the traditional art forms alive, I think it is equally important to rebrand pulp for 2019 and the years to come,” she says. Breuck agrees too. She says, “This is a genre that has always embraced all sorts of ideas and influences and aesthetic styles from global crime fiction, films, television, etcetera. It endures because of its adaptability and expansiveness.”

Pulp fiction has always thrived — in corners, away from the bestseller shelves, calling out for cheap thrills. “The covers [of these now-iconic pulp fiction books] exult in their lurid and lascivious detail, promising in their sex and gore and cacophony of colours, a wild thrill ride inside their pages and offering up the promise of violence as a promise of pleasure,” says Breuck. Going by what’s already here, and whatever the pages hold next — noir fantasies of garish robots, badass women in space, or who knows what — it’s the covers that need to reel you in.

Jessica Jani was formerly part of the editorial team at Paper Planes. Find her on twitter at @_jesthetic.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.